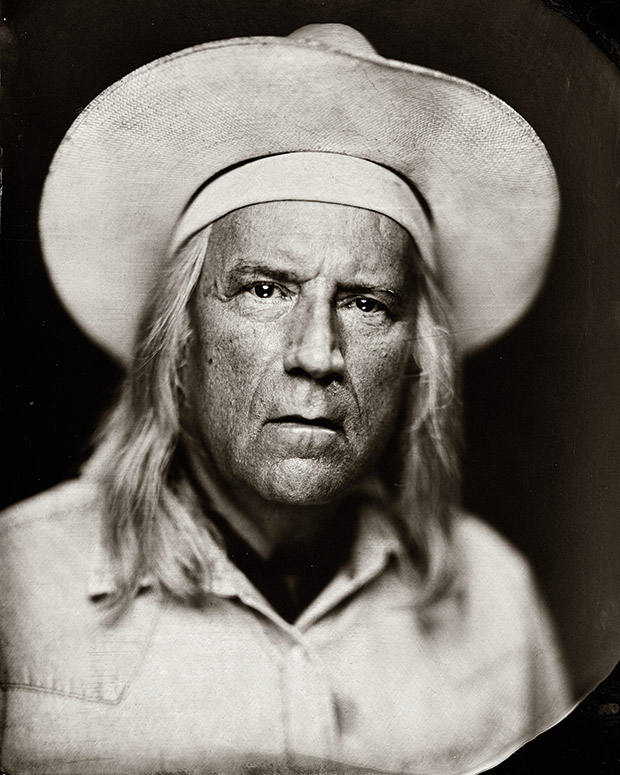

Okay, I admit it. I still like to play Cowboys and Indians. I’m fascinated by vintage images of frontier days and the Old West. The modern world with all its geegaws and gadgets is stimulating and fun, but my imagination really sings when it wanders into the territory that cowboy balladeer Don Edwards has described as “west of yesterday.”

Lumiere Tintype

The Lumiere Tintype studio is at Justine’s Brasserie (a restaurant at 4710 E. 5th St.) in Austin, indefinitely.

I was blown away, then, when I discovered the resur-

gence in popularity of an antique photographic medium called the tintype. Modern-day tintypes are images that

look like they’ve captured a moment from pioneer days. Even the name sounds old-timey. I first became aware of the process a decade or so ago thanks to the stunning, handmade images of Texas cowboys taken by photographer Robb Kendrick. And when I learned that a cool cat from England named Adrian Whipp was making

tintypes in Austin, I parked my bones in front of his large-format camera with its 120-year-old Schneider lens and faced the ever-so-briefly-blinding light of its flash.

Whipp calls his photography studio Lumiere Tintype, and he runs it with his wife, Loren Doyen. It’s actually a studio on wheels, housed in a custom-built trailer that can be pulled behind a vehicle. When the studio is not on the road, portrait-seekers flock to it at Justine’s Brasserie, a lively French bistro in east Austin. Around the state, the couple has parked the studio and created images at the Webb Gallery in Waxahachie, at Peachtree Gallery and the Charles Adams Studio Project in Lubbock, and at Big Bend Coffee Roasters in Marfa.

The tintype photographic process was patented by a fellow named Hamilton L. Smith of Ohio in 1856. Whipp told me that it started to die out in the early 1900s as traditional cameras became available, but tintypes had a good run for a few more decades as sideshow attractions. “People today are really drawn to the process because we literally make a photograph on a sheet of metal,” he continued. “First, I coat the plate with a substance called collodion. It was used as a liquid bandage during the Civil War. Then I soak the plate in silver nitrate to make it sensitive to light. That’s why they call it ‘wet plate’ photography.”

After he loads the plate in the camera, he watches his subject for the best moment to hit the shutter. “With the tintype process, the ISO—the measurement of how sensitive film is to light—is very low, so you need a lot of light when you hit the shutter.” He wasn’t kidding. The flash of light was so bright I feared I had blinked and messed up the photograph. “You blink a half second after the flash,” Whipp reassured me. “The image is always on the metal before people can blink.”

Next, he removes the plate from the camera and takes it to the small darkroom in the studio. “We pour developer on the plate for about 30 seconds,” Whipp continued. “It’s a recipe of ferrous sulphate and alcohol. Then the image starts to reveal itself, and it takes a minute to see details.” He stops the development process by flooding the plate with water and then applies a fixative to make the image stable. “It’s often magical when people first see the images,” he said. “They’re not used to seeing someone make a photograph by hand.” As the last step, he dries the plate and varnishes it with shellac, lavender oil, and grain alcohol.

Whipp describes the tintypes as black-and-white images with “coffee and cream tones” that result from the iron in the developer and the golden tint of the shellac varnish. Lumiere tintypes cost $60 for the 5×7-inch size and $110 for 8x10s. The physical image is on an aluminum plate, which takes about 30 minutes to produce, and Whipp also provides a high-resolution digital copy. Instructions for tintype care are included on the back of the plate.

Whipp never imagined he would take up an antique technique when he graduated from Leeds College of Art in 2007. “I had studied analog photography, and when I got out, suddenly everything had gone digital. It was a little disorienting.” The Brit first visited Austin for his other passion, BMX biking, met his wife here, and soon was a Texan himself. He got into the tintype business mainly on a whim. “I loved the look of tintypes, old and new, and wanted to learn the process. So I got some books, hit the Internet, and proceeded through lots of trial and error. The transition to full-blown business was actually very rapid, since I immediately fell in love with the process. My friends and family did too, and demanded that I photograph them. It didn’t take long for me to start daydreaming about how to open a full-time tintype studio.”

When I stopped by Lumiere last December, Whipp was just finishing up a tintype of a dog, and the couple after me was posing for a Christmas card. They were from Los Angeles, and the husband was a film-industry photography director who found the tintype process fascinating. “Honey, this looks great,” beamed the wife when she saw their image appear on the plate. “That’s pretty rad,” the husband agreed.

“That’s the reason people love tintypes so much,” Whipp said after the two disappeared into Justine’s for dinner. “It’s a grainless photograph, so there’s nothing between you and the image. It’s pure resolution.”