The elaborately carved woodwork throughout the Festival Institute’s three-level concert hall enhances not only the venue’s beauty, but also its acoustics.

In the fertile, rolling hills southwest of Brenham, the village of Round Top (pop. 77) possesses the reliable charms of many small Texas towns, including family-owned restaurants that specialize in pies and pastries, cozy B&Bs, and plentiful shopping. Well-known by antiques-lovers for the spring and fall antiques markets that swell the population a hundredfold, Round Top also offers a surprise for connoisseurs of the performing arts. Rising above the oaks and pines off Jaster Road, a towering cupola caps the metal roof and gabled win-dows of an elegant, 1,000-seat concert hall surrounded by gurgling fountains and lush landscaping. Amid this bucolic setting, a sign near the entrance announces the Round Top Festival Institute—an internationally acclaimed, 210-acre campus that draws performers and audiences from around the world.

Gardens and fountains contribute a European vibe to the 210-acre campus.

Here, on any given weekend, visitors attend not only concerts but also film screenings, dance performances, and arts-related symposiums, or merely stroll about the well-tended grounds, which are open to the public year round. In the spring, guitar enthusiasts congregate here for an annual guitar festival, gardeners drive in from around the state to attend a forum on herbs, and others come to hear respected poets read their works during the Institute’s yearly poetry weekend. In the summer, accomplished young musicians from around the world arrive in Round Top to take part in the Institute’s prestigious classical-music academy and give performances to audiences from near and far.

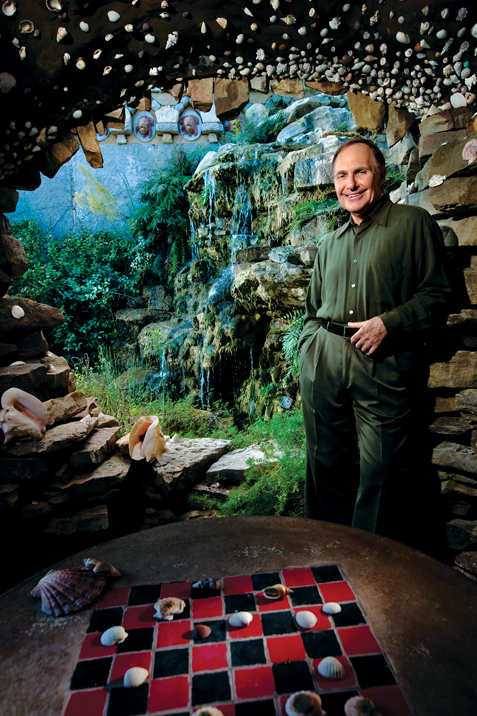

At the center of the activity is the main concert hall, which represents a kind of musical “field of dreams” for the Festival Institute’s founder, James Dick. A Kansas native, Dick received his training at the University of Texas at Austin before launching an international career as a concert pianist. The Festival Institute, which celebrates its 40th anniversary season this year, got its start in 1971, when Dick, inspired by his love of teaching, initiated a summer program for budding pianists to hone their skills amid the scenic backdrop of Fayette County.

Inspired by his love of teaching, pianist James Dick founded the Festival Institute in 1971.

What started as a 10-day series of master classes for a small number of pianists now spans six weeks, from June through mid-July, and accommodates more than 80 international students (average age: 21) who specialize in piano, strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. The Institute grants full scholarships to participants, who must audition for a coveted spot in the program, and when accepted, train under six different conductors and a renowned faculty. Throughout the summer weeks, visitors can hear strains of classical music wafting across the grounds as the musicians rehearse for the popular weekend concerts, many of which are free to the public.

After the students leave, the Institute hosts an eclectic lineup of public performances and events known as the August-to-April Series. The 2009–2010 season offered such diverse acts as the Chamber Orchestra Kremlin, the Synergy Brass Quintet, the International Guitar Festival, the Texas Medical Center Orchestra, and the Gay Men’s Chorus of Houston. (The 2010-2011 calendar comes out in late April.)

In the early days, before the hall was built, the Institute held concerts by students, teachers, and visiting orchestras in an open field, with the musicians performing on a massive mobile stage. Audience members sat on bales of hay or brought their own folding chairs. Ivy Geiger, a longtime supporter of the Institute, recalls how she and her late husband lounged on blankets under the stars with Brie and champagne—waiting for the music to crescendo before daring to pop the cork.

“People loved it. It was very pastoral,” Dick recalls. Yet the summer heat wreaked havoc on the instruments and wearied the musicians, who endured rehearsals in blistering temperatures. Sudden downpours and the rumble of passing cars sometimes interrupted the concerts. Eventually, Dick decided to build an indoor venue.

Construction on the Institute’s concert hall began in 1981. For more than a decade, local craftsmen labored to embellish practically every inch of its interior with ornate woodwork. Daylight streaming in from the high windows illuminates the theater’s red silk-upholstered seats, and four wood-and-glass chandeliers glitter overhead. After performing here in 2004, members of the Quaternaglia Guitar Quartet from Brazil proclaimed the hall “a temple to music.” Indeed, the building’s inspired Gothic design perfectly underscores the spiritual power of music to uplift the soul.

Over the past four decades, the Institute has gradually expanded from six acres to 210 and now encompasses nearly 20 buildings, which are used as practice rooms, performance and reception spaces, and accommodations for students, performers, and conductors.

Across the street from the concert hall, the Menke House, a two-story Victorian with gingerbread trim, houses a reception parlor, guest rooms, and a dining hall for the staff and visiting musicians. (Except during the summer session, lodgings on campus are available to the public attending events, too.) Nearby, the 1883 Edythe Bates Old Chapel, brought here from La Grange and restored, serves as an intimate setting for chamber music, organ recitals, lectures, and film screenings. Behind it, a stone archway leads downstairs to the Institute’s coffee shop, Kafe Kaffeine, which serves coffee and wine after some performances. Butterflies flit among the beds of colorful flowers that frame the chapel’s expansive plaza.

For visitors who want to explore the grounds, five miles of hiking trails connect the campus’ various buildings and meander through the tree-covered countryside, where stone bridges arch across shallow ravines and rustic wooden benches and stone sculptures punctuate the landscape. One path leads to an herb garden set amid faux Roman ruins, where fragrant rosemary and oregano plants perfume the air. Another leads to the raised beds of a medicinal garden, arranged by country of origin. Here, visitors can revel in the enticing aromas oflemon verbena, lime balm, and licorice, or marvel at exotic species such as the Australian emu bush, prized by Aboriginal tribes for its healing properties.

The Festival Institute now attracts some 35,000 visitors each year with its scenic beauty, astonishing concert hall, nationally known performers, and sheer diversity of offerings. While music remains the main draw for most visitors, the Festival Institute has grown to embrace other aspects of the arts and humanities, organizing annual forums on theater, poetry, herbs, and museums and amassing a collection of rare books, audio recordings, and artifacts related to music, Texas history, gardening, and decorative arts. Two museum galleries flank the hall’s reception area-one featuring objects from the estate of the Texas-born composer David Guion, and the other devoted to the heirlooms of the Oxehufwud family, Swedish immigrants who settled in La Grange.

And still, the Festival Institute is not yet complete. On one side of the concert hall, concrete blocks and exposed rebar indicate an addition in the works, and Dick admits that he would like to add writers, painters, and composers to the mix of visiting artists. Dick keeps his sights set on the future. ”You don’t count the years,” he insists. ”You make the years count