The South Texas Heritage Center takes visitors back to the region’s frontier days.

The freight courier and ox-drawn cart in the entryway of the new Robert J. and Helen C. Kleberg South Texas Heritage Center at the Witte Museum in San Antonio give visitors a hint that they’re in for a thoroughly modern, yet authentic, telling of the region’s colorful history. The well-worn wooden carreta dates from the 1850s, while the freighter mannequin speaks to viewers with holographic images projected onto its face.

The combination of interactive technology with a pre-industrial transportation relic provides the perfect introduction to the rich history, legend, and lore revealed in the Heritage Center’s expansive portrayal of South Texas life. The museum entertains as much as it educates with a combination of rare artifacts, photography, audio an video exhibits, and interactive features.

The center blends historical artifacts, like an ox-drawn cart, with modern architecture and interactive exhibits.

The 20,000-square-foot, two-story South Texas Heritage Center opened last May, making it the newest addition to the venerable Witte Museum. The Heritage Center gives the Witte a permanent space to interpret the distinct cultures and traditions of South Texas, as well as San Antonio’s prominence as an economic and cultural hub in the region’s development.

Ox-drawn cart in the entryway of the center

The museum building itself embodies a striking combination of old and new—one section is housed in a 1930s wing of the Witte called Pioneer Hall, while the adjoining section is newly constructed of glass, steel, and limestone. Designed by the local architecture firm Ford, Powell & Carson, the light-filled atrium of the new section provides a view of the museum gardens, a limestone amphitheater, and the San Antonio River.

Venturing to the second floor, museum-goers enter a gallery titled “A Wild and Vivid Land: Stories of South Texas.” The first part of the exhibit is designed to represent Main Plaza, San Antonio’s central business and gathering place in the 1800s. Visitors can step into a re-creation of the C.H. Guenther Mercantile, where the household goods on view include copper pots, china dolls, and Texian Campaigne china produced in Staffordshire, England, and decorated with scenes of the U.S.-Mexican War of the 1840s. A touchscreen display provides short descriptions of each object.

Other displays in the plaza showcase such items as a vintage Menger Hotel ledger, a Bowie knife found on the San Jacinto battlefield, and a sword that Lieutenant Colonel James Neill presented to William Barret Travis when Neill departed the Alamo in February 1836, leaving Travis in command. “The sword was found in a 1950s Alamo dig and presented to the city,” explains curator Bruce Shackelford.

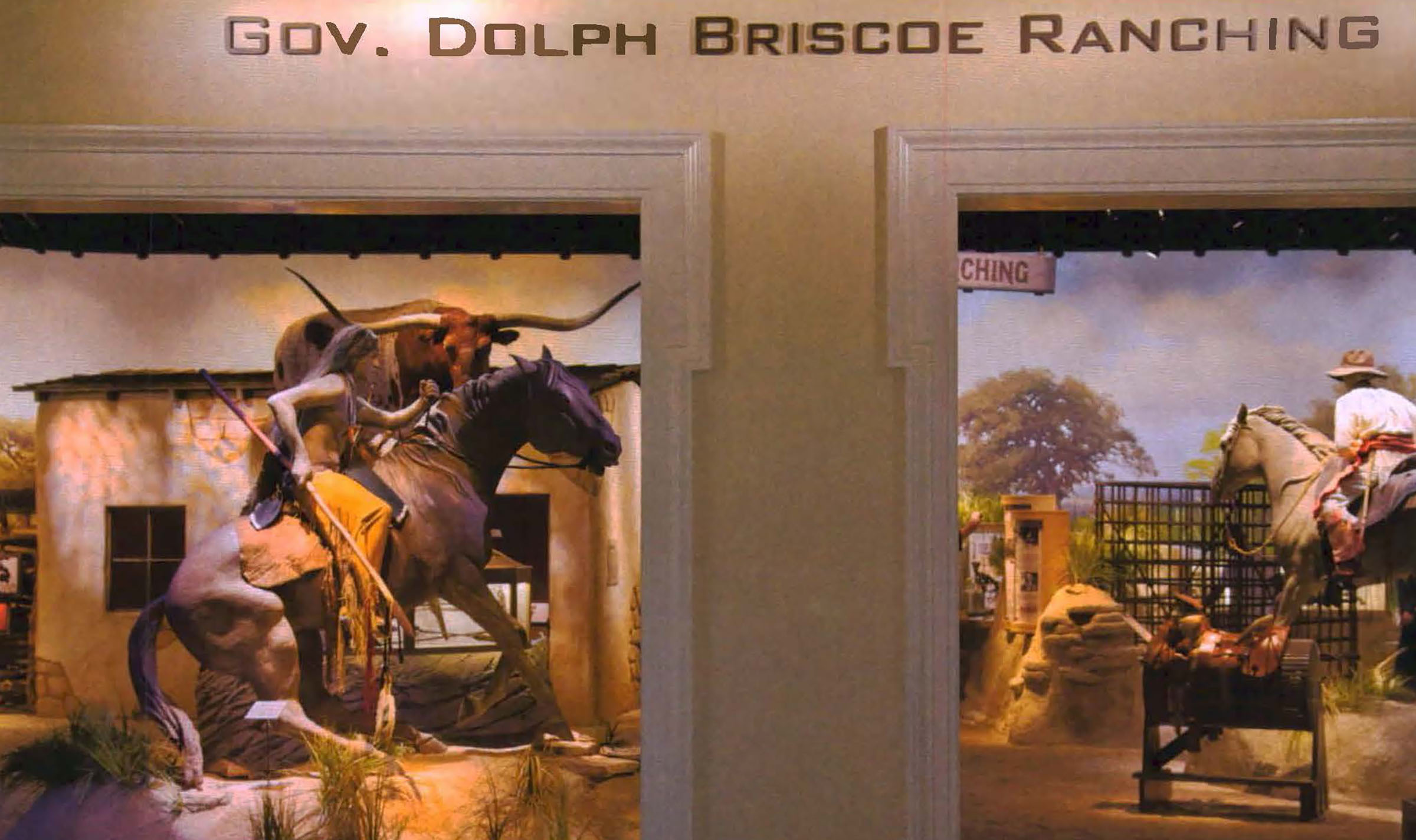

Visitors to the center explore ranching life and the tools that South Texas settlers used to scratch out a living.

The plaza gallery also includes a display about conflicts on the frontier, with relics including a gold-plated sword presented by residents of Kinney County to General John Bullis, an 1870s eagle feather war bonnet owned by Yamparika Comanche Chief Tabananica, and a beaded Apache blouse. Audio narration recounts the tragic story of the 1840 Council House Fight on Main Plaza, in which some 35 Penateka Comanches were killed. A photo of the captive Apache Geronimo illustrates the time he spent at San Antonio’s Fort Sam Houston in 1886.

Also in the plaza gallery, enlarged images of “chili queens” and their customers provide a vivid sense of one of the Alamo City’s most storied culinary traditions. The women sold spicy fare from portable stoves in the city’s plazas, reaching the height of their popularity in the late 19th Century.

The museum’s second-floor gallery is called “A Wild and Vivid Land: Stories of South Texas.”

Continuing in the second-floor gallery, visitors enter the Witte’s former Pioneer Hall Ballroom. A sweeping mural—created from nine of the late San Antonio artist Porfirio Salinas’ paintings—covers the upper halves of three walls. The mural sets the room’s tone with its depiction of a South Texas day from sunrise to sunset.

The gallery’s exhibits range from the daily lives of ancient Texans, represented by such artifacts as a pair of fiber sandals, to the stories of such trailblazing 20th Century South Texans as Edgar Gardner Tobin, the World War I flying ace who pioneered aerial land surveying, and O.S. Petty, an engineering genius who developed technology that could amplify and measure vibrations underground. In between, visitors learn about ranching, trail drives, law enforcement, irrigation, surveying, and South Texas oil booms, rounded up in a storyteller style that is designed to intrigue grade-schoolers and scholars alike.

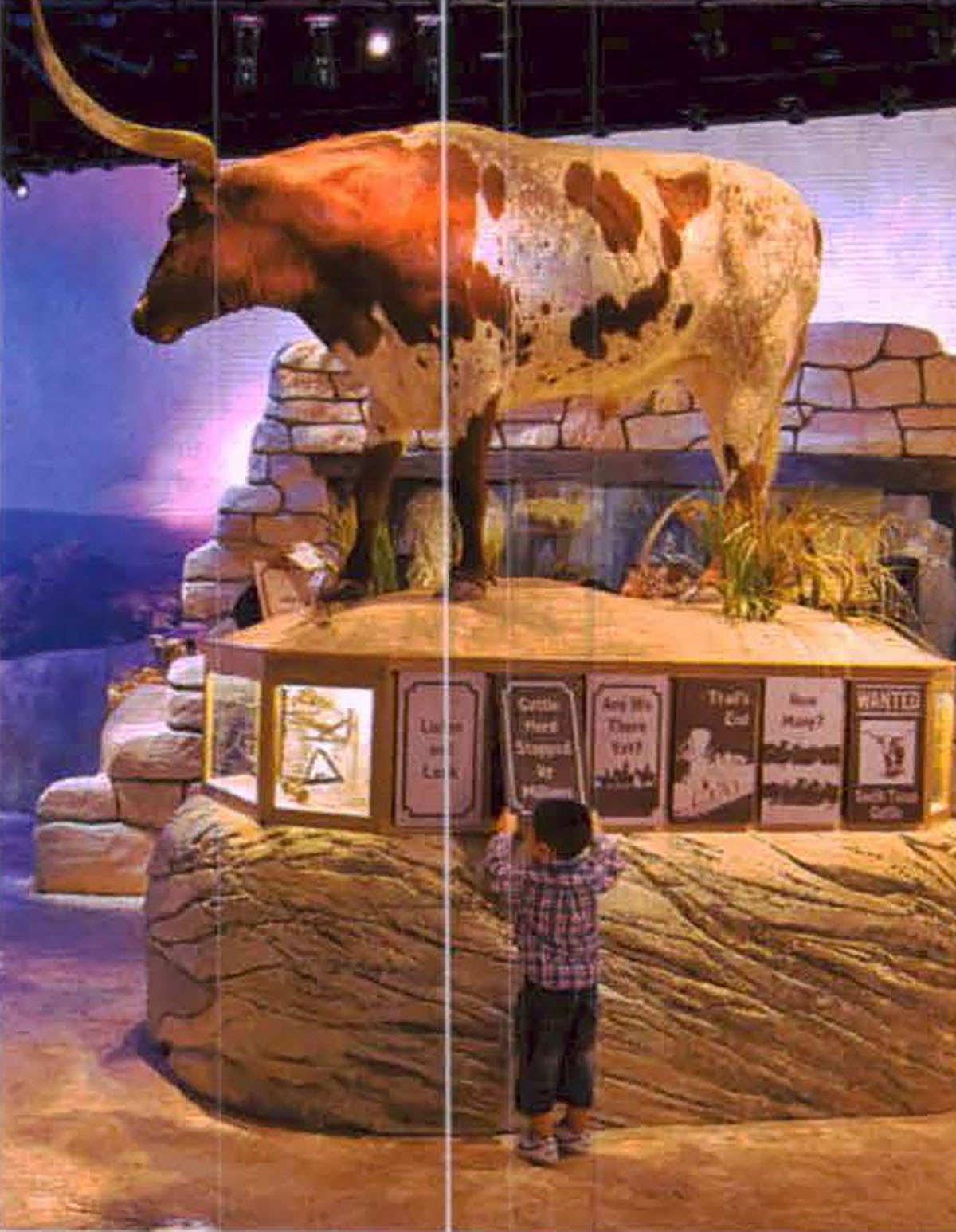

Longhorn cattle were an important part of the South Texas economy in the 1880s.

In a display on cattle brands, for instance, we learn the story of Esther Clark Watson and her broken-heart brand. When the Gonzales County rancher branded her cattle in the 1850s, she did so with a broken heart. Clark’s first husband had died on the job as a freighter. The second, it is said, perished at the Alamo. Then, in 1849, the third set out for the California gold fields, never to return. So Clark designed her broken-heart brand in the shape of a heart tom asunder by a vertical line.

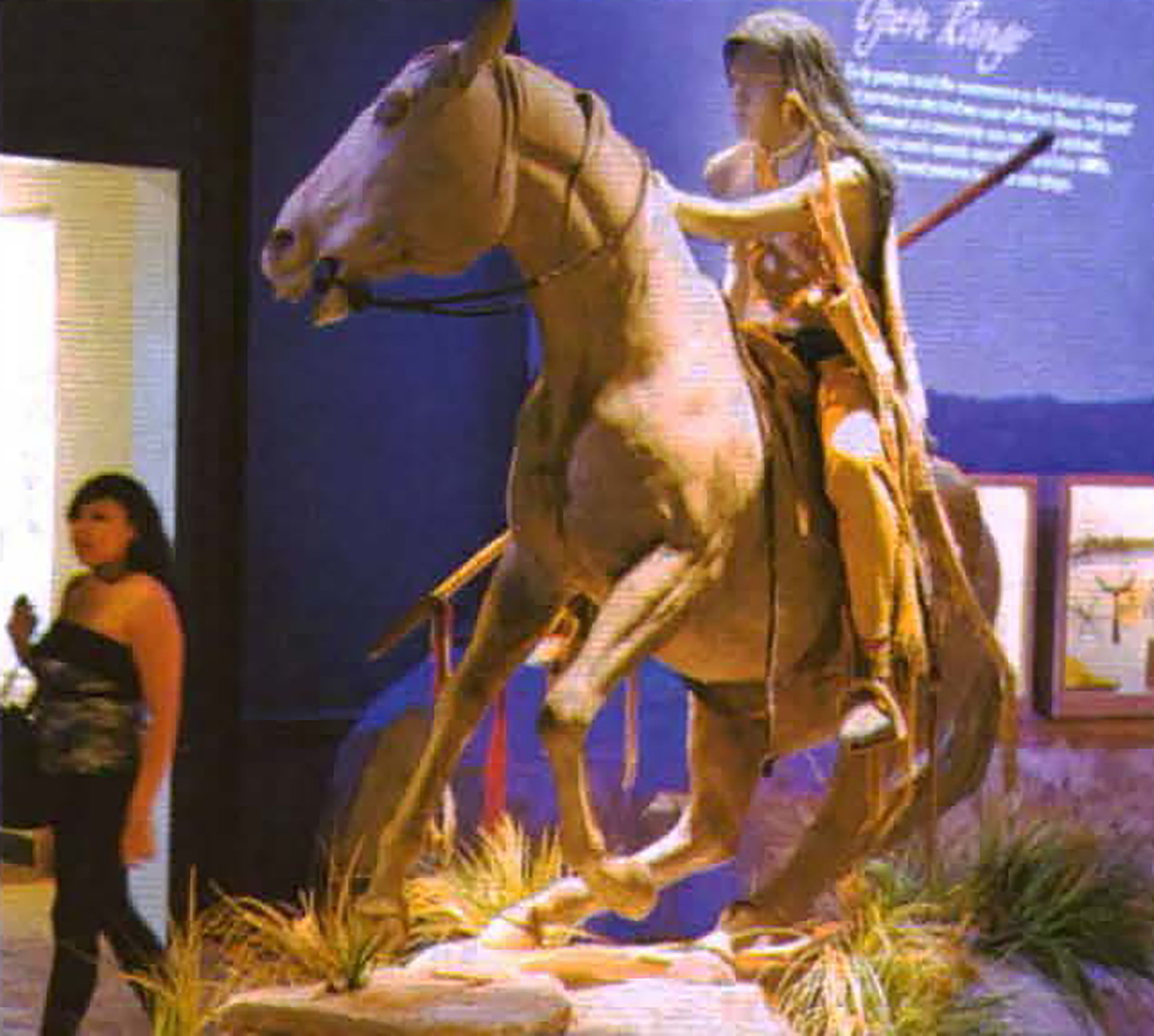

The room’s exhibit also includes life-size riders on horseback, frozen in fiberglass, depicting a Spanish vaquero of the late 1700s, a Comanche hunter-warrior of the 1850s, and a 1930s portrayal of Helen Kleberg, wife of King Ranch heir and president Robert Kleberg. Museum signage explains that the Klebergs “created the world image of a Texas ranch family in the 1900s.” According to the New Handbook of Texas, Helen Kleberg served as the model for Elizabeth Taylor’s character in the movie Giant.

Vaqueros and cowboys treasured their firearms for protection.

The tools of South Texas ranching life are grouped together in a large exhibit. It includes a pair of 1870s “shotgun” chaps, named for their straight-legged style, and some 1930s “batwing” chaps that kept legs cooler. The display’s computer touchscreen provides handy information on the sombreros, Stetsons, boots, and spurs that the ranch hands relied on. It notes, for instance, that a saddle common to northern Mexico circa 1870 had a larger horn for winding rope and that a fancy, early-20th-Century Mexican bridle was custom-made for oilman Barney Halloran.

Downstairs, in the former Pioneer Hall, the Heritage Center continues the building’s tradition of displaying the portraits of members of the Old Time Trail Drivers Association. A new touchscreen database pops up portraits of trail drivers not represented on gallery walls.

A second downstairs gallery, the Russell Hill Rogers Texas Art Gallery, offers changing exhibits. On view through May 27th, Artists on the Texas Frontier includes such paintings as Theater at Old Casino Club in San Antonio by Carl G. von lwonski, San Pedro Springs Park by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, and Crockett Street, Looking West, San Antonio de Bexar by Karl Friedrich Hermann Lungkwitz.

The Heritage Center chronicles the history of Native Americans in South Texas.

The Heritage Center also draws visitors into the past with regularly scheduled plays and demonstrations that illuminate the everyday life of 19th-Century South Texas. The plays, which take place in the amphitheater, feature characters both real and imagined discussing their lives, traditions, and cultures. This spring, the chili queens will take the stage for their tum in the spotlight. A new play about the old-time street cooks by San Antonio playwright Marisela Barrera opens March 16th. After a few hours of absorbing the rustic sites, sounds, and people of South Texas, a plate of the chili queens’ zesty market fare would surely hit the spot.

The Witte Museum is at 3801 Broadway, San Antonio 78209. Call 210/357-1900; wittemuseum.org