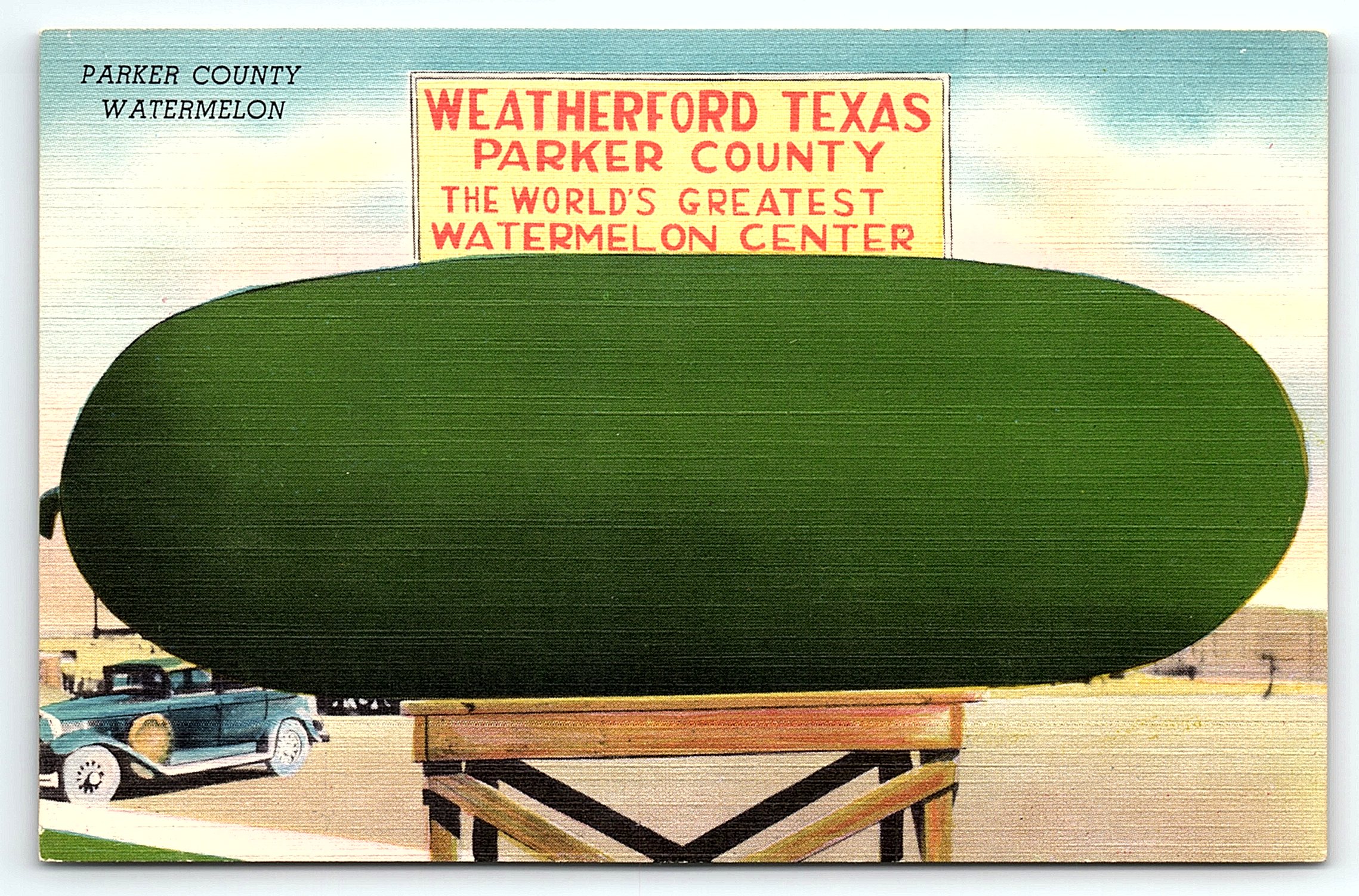

A vintage postcard from Primetime Paper Peddler in Georgia displays an artist’s rendering of the watermelon statue that stood outside the Parker County Courthouse in Weatherford with the words: “World’s Greatest Watermelon Center.”Courtesy Primetime Paper Peddler

Heading into the second weekend of July, residents from all over Parker County brace themselves as their historic square transforms into a vibrant jubilee celebrating all things peach. The scented air—infused with the sweet aroma of perfectly ripened fruit—and masses of crowds signal the return of the Parker County Peach Festival.

It may surprise Texas peach lovers that Parker County—not Fredericksburg, where peach orchards proliferated before wineries took over—has been designated the official Peach Capital of Texas since 1991. This year marks the festival’s 38th year, and as an exaggerated microcosm of agriculture’s hold over the region, the annual event gives visitors a glimpse into the community’s affection for peaches.

Yearlong, however, locals live almost daily with the fruit, from marketing embellishments at small businesses to peach-filled menu items at restaurants. A great reminder of the fuzzy feelings about peaches can be found in the county seat of Weatherford: a peach mural adorns the exterior of a century-old train depot that’s now the home of the visitor’s center near the heart of town.

But neither visitors nor many locals may be aware that long before Parker County was the peach capital, it was the “World’s Best Watermelon Center.”

In the early 1900s, people far and wide knew of Parker County watermelons. The story—at least as told by those whose families have been here long enough to know—is that banker G.A. Holland of Weatherford and Luther Lyle of Peaster shipped a variety of Parker County watermelons to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, where 12 claimed the top prize for their impressive weights. As a result, Parker County was put on the world map for agricultural success.

The achievement quickly sparked a craze countywide, pulling new growers out of the woodwork. On any given market day for the next 20 years, wagonfuls of melons would fill the same town square that’s home to the Peach Festival a century later.

“There were watermelons everywhere,” says Peggy Hutton, a Parker County native who recently retired from the Weatherford Chamber of Commerce and is married to Gary Hutton of Hutton Peach Farm, the primary grower of peaches in Parker County. “You could look over into the pastures while driving down the road and see them because they were 100-plus pounds,” she says.

Similar to how today’s residents celebrate the peach, the entire community was once adorned with watermelon memorabilia—from colorful displays at roadside stands to the drumhead of the high school band (even though the mascot was the kangaroo) to a county postcard that proudly proclaimed itself as the “World’s Greatest Watermelon Center.” In 1928, a giant watermelon statue even represented Parker County in the West Texas Chamber of Commerce parade. Afterwards, the colossal tin melon sat atop a wooden landing on the courthouse lawn for over a decade. “And no one knows where it went,” Gary says, chuckling.

A crew of men prepare harvest watermelon on Chandler Melon Seed Farms in Poolville in the 1940s. Photo courtesy Charles Sanders.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, Weatherford had become the nation’s largest-volume shipping point for watermelons by 1925. And in the county’s northernmost town of Poolville, Charles Sanders recalls growing up during the craze. He spent hours in the watermelon fields with his grandfather as a young boy, he says. From the time he learned to drive a tractor at 5 years old to when he grew his last commercial crop in 1974, he was on the family’s multiple farms growing, picking, and seeding fresh watermelon. It was his grandfather, Emery Chandler, who started the business as a teenager in 1910, just after the county gained fame for the crop but right before its production heyday.

Now 84, Sanders is the last remaining of his family. Battling Parkinson’s disease, he becomes emotional as the memories come flooding back to him. When I ask about this time in his life, he has his wife of 65 years, Doris, recite his favorite memory while working on Chandler Melon Seed Farms.

“He would sit with his grandfather, almost every day, and they would eat the lunch they had packed under a tree in the shade and just talk about life,” she says.

Charles Sanders (left) stands in front of the watermelon fields at Chandler Melon Seed Farms in Poolville alongside his father, brother, and grandfather in the 1940s. Photo courtesy Charles Sanders.

Sanders also vividly remembers the toil and sweat that went into cultivating watermelon—from preparing soil and planting seed to constant watering and tending during their growth, and then doing it all over again. And the season always fell during the hottest months. “We could plant on Good Friday and have ripe watermelons by Fourth of July,” he says.

But it also had one major perk: free, all-you-can-eat watermelon. After a long day’s work, Sanders says his family would often head back to the fields, salt and knife in hand, ready to savor the fresh fruit right off the vine.

Watermelon continued to lead as Parker County’s favorite fruit through the 1960s, and it was still named among the world’s best by the New York Times as late as 1993. No one quite remembers when Parker County watermelon had finally become a thing of the past, and more importantly, an exact reason why.

“Well, the soil was different,” Doris suggests.

“It changed with transportation and the new ways they could make a living after World War II,” Gary recalls.

“People stopped farming in general,” Peggy Hutton says. “Younger generations didn’t want to do it anymore. And it fell by the wayside.”

Leaving behind a sense of mystery and nostalgia for the few who do remember, the voluptuous fruit had simply phased out.

Perhaps, a new generation will discover the delight of biting into a slice of freshly ripened, locally grown watermelon. And perhaps, in that discovery, the watermelon will find a home in Parker County once again, no longer a forgotten relic of the past but as a cherished part of the county’s heritage. Otherwise, with every passing Peach Festival—each more extravagant than the last—the community will take one step further from its watermelon days.