The late Townes Van Zandt performing in Germany in 1995. Photo courtesy Michael Schwarz/via CC BY-SA 3.0

It’s a blustery, dark, cold January day at an old cemetery in Dido. Were it not for the two Texas Historical Commission markers and the signage for the United Methodist Church, this ghost town 40 minutes northwest of downtown Fort Worth on the shores of Eagle Mountain Lake would be all but imperceptible to passersby. The cemetery occupies a couple of acres, its lake view now obscured by a golf course. In front of the cemetery, a sign reads: No Benches, Smoking, Alcohol, Glass Containers, Trees, Plants, Items on Grass.

Most of the graves in the small cemetery adhere to these prohibitions. But the one I seek does not. The person it belongs to wasn’t known for playing by the rules—and 27 years after his death, he continues to break them.

JOHN TOWNES VAN ZANDT

March 7, 1944

January 1, 1997

TO LIVE’S TO FLY

On the musician’s grave rest flowers, pieces of jewelry, and three emptied Lone Star bottles with yellow roses stuffed in them. Dead at of 52—44 years to the day one of his musical heroes, Hank Williams, died—Townes Van Zandt created his songs like “White Freightliner Blues,” “Pancho and Lefty,” “If I Needed You,” and “To Live’s To Fly” in a life marked by depression, failed marriages, and substance abuse, with little Music City financial success and opulent living to show for it. His life and music stand at a distance from Fort Worth, where he was born 80 years ago, and from its satellite where his ashes were spread. Even though cities like Houston, Austin, and Nashville played major roles in Van Zandt’s adult artistic development, Fort Worth was the first place to sow his imagination.

Though Van Zandt’s been gone for decades now, traces of his legacy can still be found around his hometown. Since 2013, Fort Worth arts venues have hosted homeTOWNESfest, an annual celebration of Van Zandt’s legacy at the historic Southside Preservation Hall (in the same area as the musician’s first home) in honor of Van his 80th birthday. This year’s event takes place March 9-10.

For fans of Van Zandt, the fest is just one of many places you can visit to find the spirit of the Texas musician around Fort Worth this month. Here are some other places to find the spirit of Townes Van Zandt around Fort Worth.

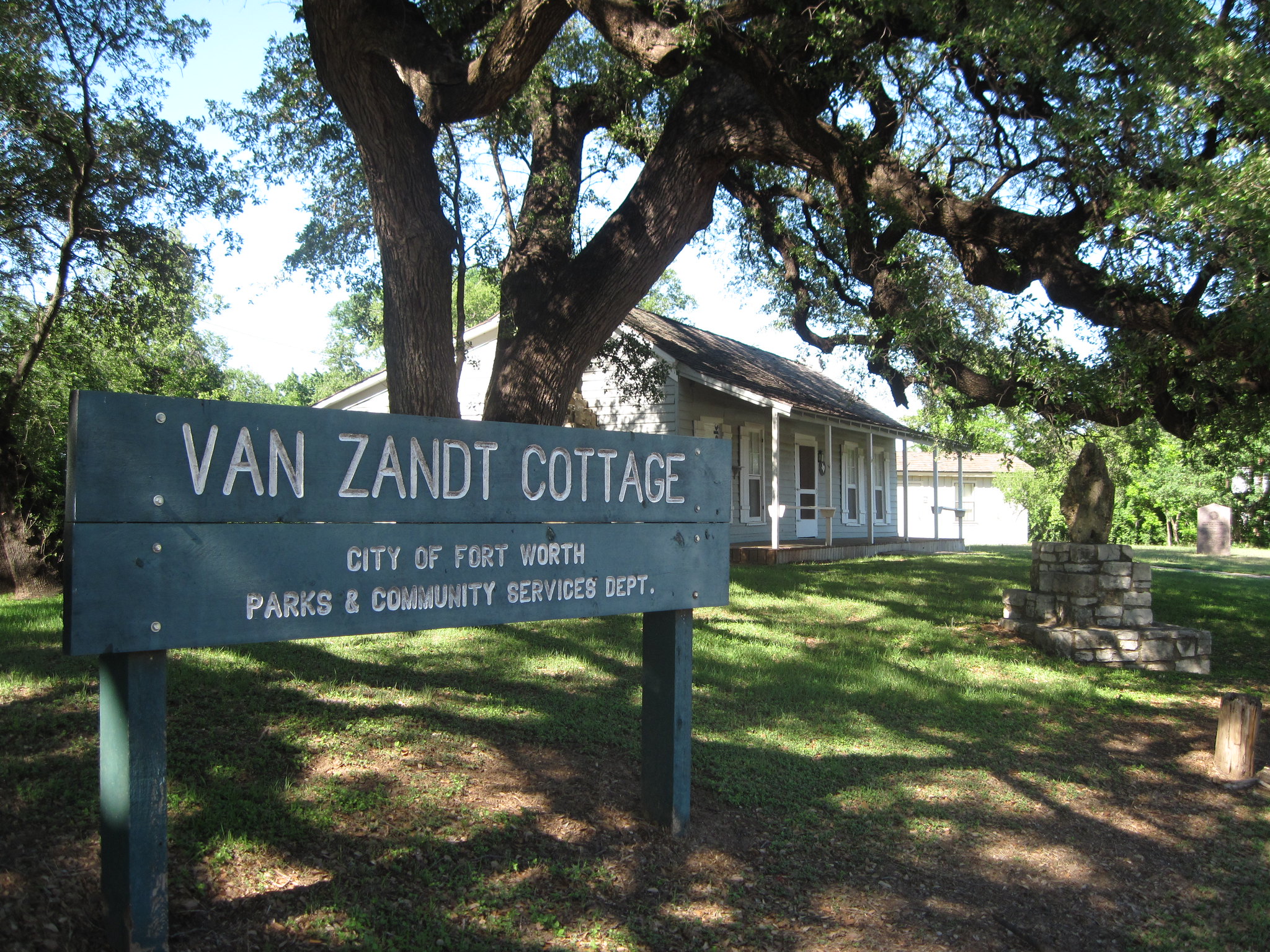

The Van Zandt Cottage in Fort Worth. Photo by Nicolas Henderson via Flickr

Van Zandt Cottage

Van Zandt was a member of a wealthy family that descended from Isaac Van Zandt, a leader of the Republic of Texas. Isaac’s son, Townes Van Zandt’s great-great grand uncle, Khleber Miller (K.M.) Van Zandt was a major in the Confederate army and one of the founders of Fort Worth. Although Van Zandt didn’t spend the majority of his life in Fort Worth, he never forgot his roots: He directed that his ashes be deposited in the Van Zandt cemetery plot in Dido.

The Van Zandt cottage is the site of the family’s origins in Fort Worth. K.M. built the cabin for his family after the Civil War on the outskirts of the then-tiny settlement of Fort Worth (1865 population was about 250). The cabin, which the state restored in time for the 1936 centennial, housed the K.M. Van Zandts for a decade. Today, the cottage is owned by the city of Fort Worth’s Park and Recreation Department, which opens it to the public on select dates throughout the year.

The cabin stands as a testament to K.M.’s decision to dedicate his time and money to developing Fort Worth. According to the Texas State Historical Association, K.M. helped build a streetcar system that was one of the first in the state. He also played a role in bringing the Texas and Pacific, the Santa Fe, and the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas railroads to Fort Worth. But compared to the buildings that make up the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo grounds and the gems of museums that Louis Kahn, Philip Johnson, and Tadao Ando built, the Van Zandt cabin strikes a bathetic note: It memorializes a time before all this development. Though this family laid the foundation for the Fort Worth we know today, their legacy is memorialized by a cabin the size of a two-car garage. 2933 Farm House Way; 817-392-5881; logcabinvillage.org

Record Town

Musician Guy Clark and Van Zandt on the wall at Record Town. Photo courtesy of Record Town

Record Town cuts across Cowtown cultural stereotypes since its opening in 1957. Priding itself on the rich blues tradition that distinguished the Fort Worth music scene and formed the basis of Van Zandt’s musical sensibilities, Record Town offers a selection that can only be described as eclectic: It is one of the few places in town to find bargain vinyl of Townes’ favorite musicians, including Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and even Mozart. Record Town not only provides insight into one the musical beginnings of Van Zandt, but it serves as an unofficial museum of the Fort Worth music scene. 120 St. Louis Ave., Suite 105; 817-926-1331; recordtowntx.com

Fairmount and Magnolia Avenue

No one who listens to Van Zandt’s songs would accuse him of sedentary tendencies. “To Live’s to Fly” aptly summarizes his nomadic nature. Still, even roving artists grew up in homes, and Townes roamed the Fairmount National Historic District more so than anywhere else in Fort Worth.

Today, Fairmount is one of Fort Worth’s most walkable and historic neighborhoods, a brightly colored array of homes with historical markers and bohemian yard art. Magnolia Street, with its restaurants, offices, and boutiques, borders Fairmount on the north. Bars on Magnolia like The Boiled Owl Tavern and The Chat Room do justice to the spirit of a king of quirky and dingey dive bars. The crowd at Chat Room resembles the hippie-country fan base of 1970s Texas country, folk, and outlaw music.

Acre Distilling Co.

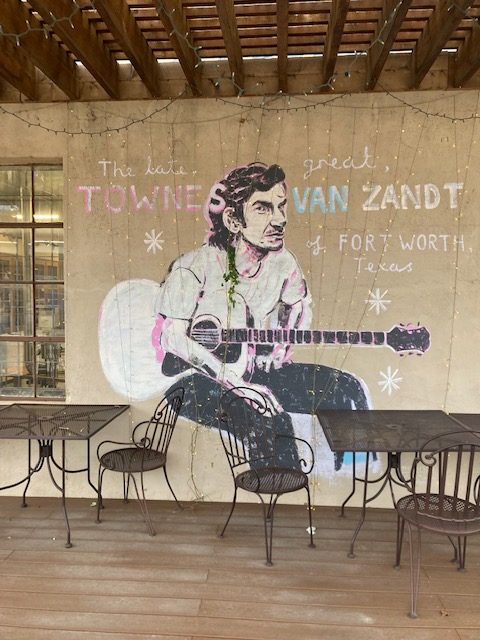

Toward the back of Acre Distilling Co., Townes Van Zandt looks out on the old Santa Fe Railyard.

The Van Zandt mural at Acre Distilling Co. in Fort Worth. Photo by Daniel Orr

During the height of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, Acre Distilling Co. owner Tony Formby built a wooden deck in the parking lot facing the railyard. A friend of Formby’s introduced him to an Australian driving cross-country, who wanted to paint a mural on the deck. Now, J. Morrison’s mural of the “Late Great Townes Van Zandt” continues to look out on the railroad that his ancestors helped bring to his hometown. Formby notes it has become a visitor favorite, especially on nights when Acre Distilling Co. brings live music to the deck.

The mural calls to mind the vagabond life Van Zandt led after he got out of Fort Worth. In his 52 years, he lived his lyrics from “Pancho and Lefty”: Living on the road my friend was going to keep free and clean / Now you wear your skin like iron / And your breath’s as hard as kerosene. But now, 80 years after his birth, here he is—back home.