Wedding guests at the writer’s wedding in La Grange partake in the bridge portion of the Grand March. Photo by Helo Photography.

The dance starts with our elders. Two old-timers who know what it means to spend decades together in marriage and come out wealthier in love. That’s what the Grand March requires—a head for tradition and a couple of young hearts.

When I told my future in-laws that I wanted a traditional Texas wedding, they didn’t know what to expect and I didn’t really know how to explain it. But I knew there would be a Grand March. This promenade of a folk dance hails from the old country and is used to introduce a new bride and groom to their families. The Czechs will tell you it originated in the Slavic regions; the Germans will tell you it’s German through and through. But all can agree that it’s a dance known well in rural Texas, specifically those parts where the kolaches are fresh and the language still carries a hint of Texas German.

According to Gary E. McKee, historian and editor of La Grange-based Texas Polka News, the dance originated among peasants as a way for two families to join, meet each other, and celebrate the new union as one in their village. “Back when people did not just dance together,” he says. With the Grand March, you could actually hold a woman’s arm in public. “It was the really hot thing to do,” he adds, laughing.

The March goes a little like this: first, the formation. An announcer hollers for everyone to “Line up for the Grand March!” And everyone—and I mean everyone—pairs up and falls in line. An elder couple experienced in the dance goes first. Then, the bride and groom, their parents, their grandparents, and the wedding party follow. From there, it’s a free-for-all rush for everyone to get in line in time for the song to start. We throw big weddings in Texas, so you’ll need a big dance hall, something of which we have no lack.

“If you’re single and a little freaked out that there are so many couples on the floor, just grab a partner or take a child,” says Lori Najvar, an Austin-based folklorist, documentarian, and frequent dancer of the March. “That’s what I love about the Grand March—it’s very inclusive. It’s an opportunity for everyone to get out of their chair and see everyone.”

The dance is traditionally performed to “Under the Double Eagle,” which is a march, but there’s no harm in doing a two-step for the fancy and a shuffle for the shy. Like any folk dance, the movement itself tells a story, beginning with the wedding party dancing into the hall together. This is meant to symbolize the celebration of the new life of the bride and groom as one. The couple then split and dance separately, representing the inevitable fights to come in a marriage. Everyone comes back together—the kiss and make up, so to speak, though the romantics always kiss before they part.

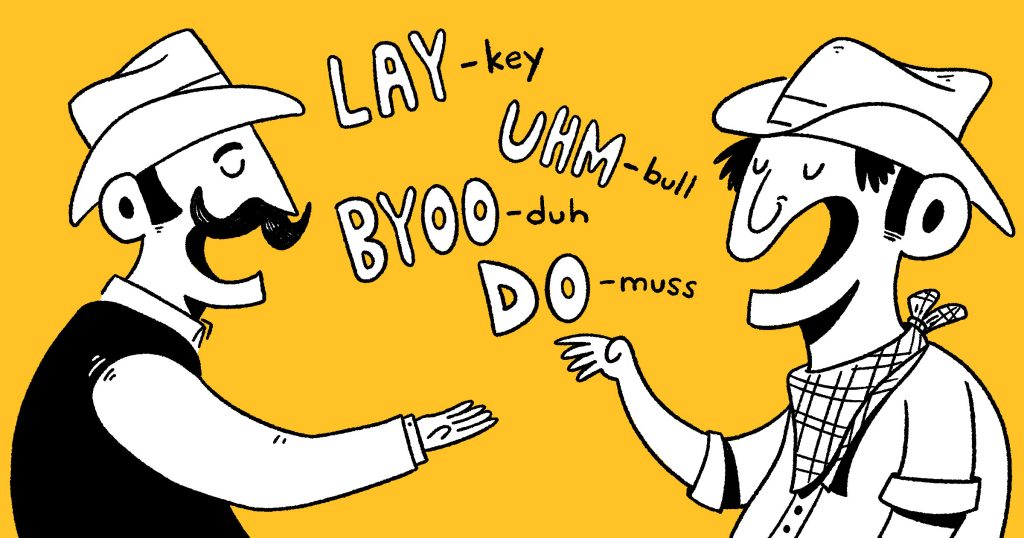

Next is the bridge, where everyone raises their arms and joins hands with their partners to show the marriage growing stronger over the hardships. Couples tunnel through the bridge that grows longer and longer as more loved ones join in.

“That’s my favorite part,” Najvar says. Full of joy, it puts a smile on every face. Old cowboys become kids again, and kids marvel at even the old cowboys joining in to tunnel through their loved ones’ arms.

The dance ends in large, concentric circles with the newlyweds at the center. A circle for inner family, a circle for close friends, a circle for community—all are there to surround the couple as they depart on their new life together. All are there to wrap the couple in love.

While I sure do love the bridge, my favorite part is the circle of held hands, the slow dance at the middle. The music goes soft, the lights go low. It’s time for the first dance. The newlyweds wrap their arms around each other and the party wraps their arms around the couple. We all dance, rushing in to shroud the couple in privacy as they share a kiss.

According to Najvar, who also serves as director of PolkaWorks, a nonprofit that uses multimedia to preserve cultural stories, couples are keeping the custom alive. “There seems to be a resurgence of the Grand March in weddings these days,” she says. “Lot of weddings being held in those old KC [Knights of Columbus] and American Legion halls again.”

As the world grows more unpredictable, it’s unsurprising that people, even the young, would want to hold on to old traditions—and share those traditions with the people joining their families.

“I didn’t want to marry someone that was going to put blinders on to my background, my small community, my Czech culture,” Najvar adds.

I concur. I myself married a Maryland boy at the fairgrounds in La Grange. We danced the Grand March in the pavilion dance hall, a venue I chose specifically for the Grand March. I knew I would dance it at my wedding no matter who I married.

My husband and I brought our favorite things to the table. We served crab dip and Utz chips for appetizers, barbecue for dinner, and bluebonnets as a bouquet. The wedding was beautiful—but it’s the Grand March everyone remembers best.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of the story said the Grand March was danced to a polka beat, but it is performed to “Under the Double Eagle,” which is a march. The story has been edited to include the correct information.