Elizabeth Wetmore spent 14 years writing her debut novel about boom-and-bust Odessa. Photo by Carrie Allen.

Elizabeth Wetmore has swiftly entered the lexicon of Texas authors writing about the state’s open landscapes, distinctive characters, and myriad complexities. In her debut novel, Valentine, Wetmore seamlessly moves between the perspectives of seven female characters to tell the story of 14-year-old Gloria Ramírez, who appears on a family’s front porch one morning after being raped. This lyrical, well-crafted narrative unfurls with a candid examination of how the brutality of this violence ripples through the working-class community of Odessa in 1976.

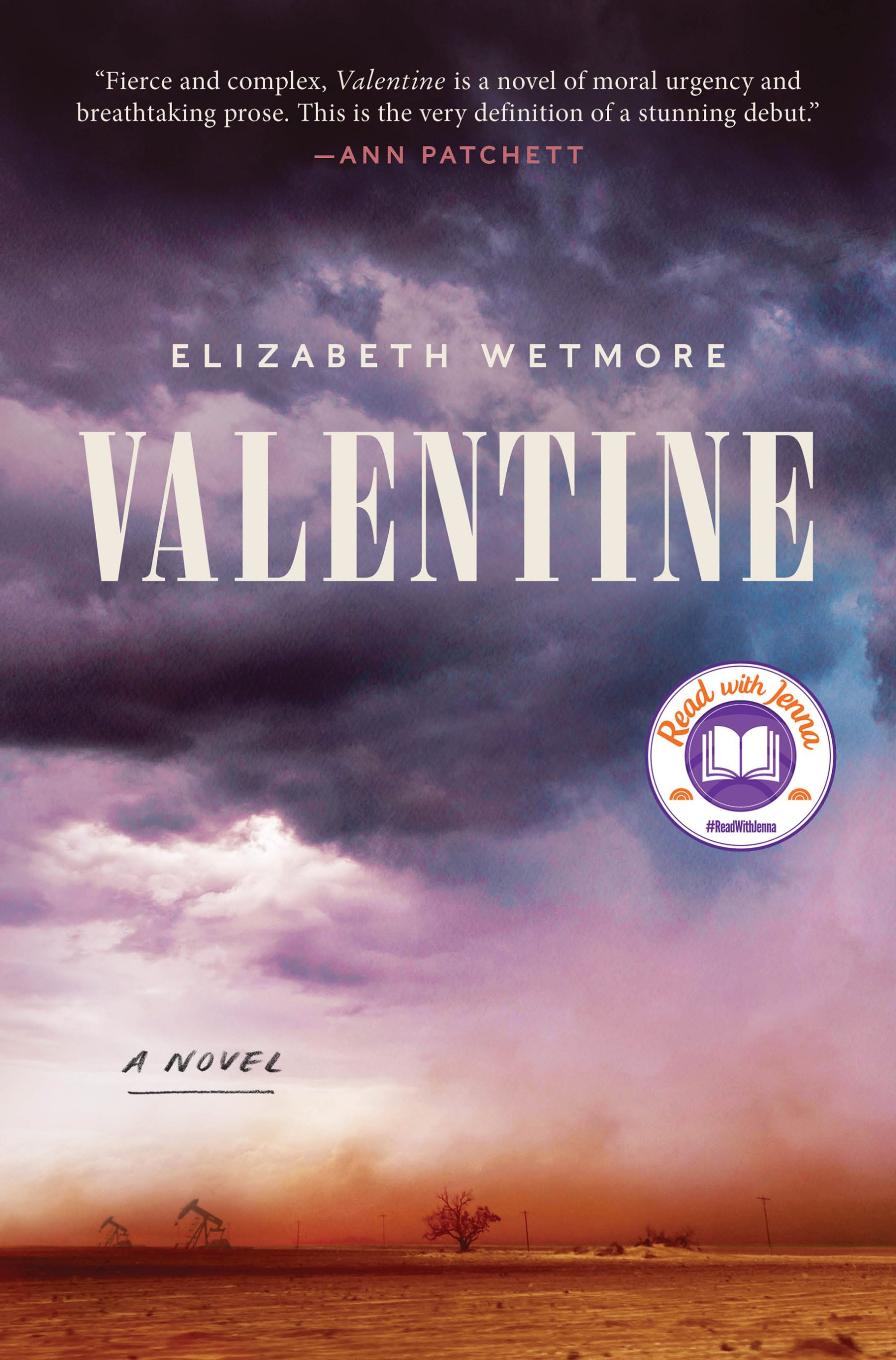

Not surprisingly, Wetmore grew up in Odessa, the daughter of a man who worked in security for a petrochemical company for more than 30 years. She has lived in Chicago, with her husband and son, for most of her adult life. After Jenna Bush Hager selected Valentine for her popular monthly book club on the TODAY show, #ReadWithJenna, Wetmore’s novel climbed onto The New York Times Best Sellers list. “The book seems to be moving people, and that makes me happy,” Wetmore says. “It has been incredibly gratifying to hear from women from all ages and backgrounds, and their delight in seeing their stories rendered on the page.”

Texas Highways spoke with Wetmore about Odessa, the dangers of the oil patch, Friday Night Lights, and more.

Why 1976 for the time period of Valentine?

Wetmore: The boom-and-bust cycle changes the entire spirit and tenor of an oil community, and I was interested in writing from the perspective of a town that is in the thick of a big oil boom. I worked on this novel about 14 years, so I saw oil booms come and go, and most recently what is going on right now. I knew that I wanted to write about a town in the midst of an oil boom because of the accompanying troubles that go along with that. On one hand, an oil boom means people have jobs and can pay the bills and save a little money for college for their kids; on the other hand, it brings with it a real steep increase in crime, a housing crisis, traffic, and noise.

Did you return to Odessa when you were writing the novel?

Wetmore: I realized in very short order that my memories were not sufficient. I had not seen my hometown—and certainly not the women—in ways that they deserve to be seen. I still have family in Midland, so I came back to Odessa as much as I was able to over the years. (My mom and dad are now retired in South Texas.) Among other things, I spent a lot of time at the downtown library and looked at old newspapers and records. I also spent a lot of time taking long drives through the oil patch. Sometimes in the morning, I would pack a lunch and just go driving for hours. That was a part of the way that I was able to connect with the land in ways that I wasn’t able to see clearly as a kid.

Odessa doesn’t necessarily have a reputation for being a particularly beautiful place. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. You don’t have to drive far to get out of the oil fields and into that beautiful high desert and the epic sky and the little critters that are always moving through the brush. For me, that was the way to get back to Texas with a tender and loving eye on my characters.

Jenna Bush Hager selected Valentine for her popular monthly book club on the Today show. Courtesy HarperCollins.

Was there a particular character who was most challenging to write?

Wetmore: Gloria, in a lot of different ways, was the most difficult character for me to write. I asked myself often, having asked a reader to witness this kind of suffering, “What was my obligation as a writer to handle it in ways that were sympathetic and nuanced and not exploitative?” When I grew up in Odessa, it was a deeply segregated town of working-class and middle-class white folks. So, Gloria and her family and her circumstances are less familiar to me than the experiences that I had growing up.

How did you avoid the pitfalls of that challenge?

Wetmore: In terms of the structure of the book, I made two choices early on—that Gloria would have the first word and the last word, and I tried the best I could to make sure that she got some of the most beautiful language in the book. That may sound like a small thing, but for me it was huge because I’m so language-conscious as a writer.

I do this with all of my characters, but with her in particular: I interrogated every choice I made. I tried to think carefully and access my own imagination and empathy and wells of compassion. I also had to acknowledge that I might not get it right—and that might be a failing of the book—and make my peace with it.

Do you feel like the men in that kind of working-class environment are being oppressed, too?

Wetmore: As I was writing Corrine’s husband, Potter, I meditated on the costs of this idea of the individual. I don’t want to give too much away, but at the end of the day, this is a man who would rather die than be seen as weak and ask for help from the woman who he loved most in the world in his time of greatest need. It’s both the way people survive in a place that is like West Texas, but also how a place like this has the enormous disadvantage of making people feel like they’re alone in the world.

My dad worked for 30 years in the safety department at the petrochemical plant in my hometown. He did a tour in Vietnam, and he came home in 1971 and needed a job badly. When they found out that he had been a medic in the war, they sent him over to safety and he worked in that department for the rest of his career. Of course, as a little girl, I would hear the whistle go off and I would hear the phone ringing in the middle of the night and I would hear my dad pulling on his clothes to go back to the plant because there had been an explosion, a chemical spill, or an accident. I remember very clearly worrying about my father’s safety, but it wasn’t until I was a woman that I looked back on my dad’s career and thought, “My goodness, what a world to survive a war and then come home and spend the next 30 years working in an environment that danger was all around you all the time.”

The voices and accents of your characters are so specific to West Texas. How did you go about capturing the musicality of these voices?

Wetmore: One of the last things I did when we were finishing up the editing process, I checked into a hotel and read the entire book aloud over the course of a weekend. It was always my hope that the music of the voices would shine through, particularly given the specificity of a West Texas accent—an accent that I’ve read is starting to disappear in some of those rural places in Texas and with people under 40.

Was there a particular piece of advice from one of your teachers that helped you during the writing process?

Wetmore: I had a workshop at a summer conference with Luis Urrea (author of The House of Broken Angels among other books), but I also see this in his work: Always come to your characters with an ethic of love, even if they are hard characters or deeply flawed characters, like a lot of mine are.

For the reader who has never been to West Texas, is there something that you hope they take away from the novel?

Wetmore: Without oil, Odessa would be just a little stop on the Texas and Pacific Railway. The entire community depends on oil and gas. Now we’re having conversations about climate change, and what I think a lot about is how do you help people who live in these communities? And what is the responsibility to do so? I hope that readers who aren’t from Texas maybe see the place a little more clearly.

Odessa is known, of course, for Friday Night Lights (age 17 on Texas Highways’ Texas Books for 100 Ages). I read the book when it was published and I reread it a few times. My sister was in the high school senior class that that book is based on. Again, I noticed with the book—and what I noticed with a lot of books that are set in that part of the world—the stories of the women and the girls weren’t always front and center. One of the other things that I hope a reader would take away is seeing these women and girls’ lives clearly, giving them a proper place in the literature in that part of the world. I thought Friday Night Lights was great, but even at the beginning I found myself wondering about the lives of women and girls who weren’t the cheerleaders.

Lastly, I hope that readers will see West Texas as a land that is worth saving, apart from the oil and gas. Fracking and horizontal drilling are having an impact on all of us—and nowhere are those impacts felt more keenly than for the people who live right there. Of course, it’s a novel, so I wasn’t setting out to teach people a lesson; I was setting out to tell a story.