Photo by Kirk Weddle

Perhaps the most striking scenery between San Antonio and Canyon Lake lies underground. The extensive cave system known as Natural Bridge Caverns is registered as a National Natural Landmark and a State Historic Site, and its otherworldly, subterranean formations date back 40 million years.

Each year, thousands of people come to take a tour; most visitors embark on a 75-minute guided excursion through what are known as the Discovery Passagesa magnificent string of underground rooms discovered in 1960 by a group of adventuresome college students.

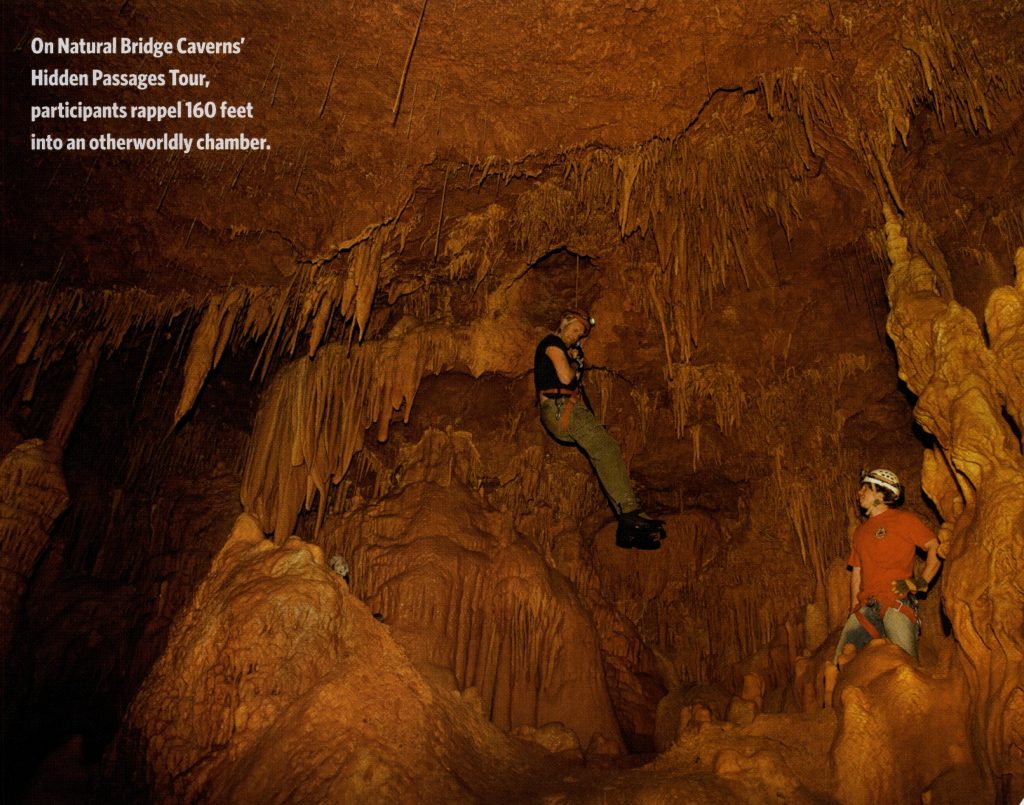

But my buddy Kirk Weddle, a photographer, wanted to experience parts of the caverns that most people don’t see. He cajoled me to join him on a Hidden Passages Adventure Tour of a wing of the cave that hasn’t been equipped with handrails, pathways, or other concessions to visitors.

Travis Wuest, Vice President of Natural Bridge Caverns, prepares us for the initial descent through a dark, 160-foot-long shaft, a mere 22 inches wide. As Wuest clips a rope to the harness around my waist, Kirk and I glance at Kirk’s wife, Tracy, who looks nervous. She decides to take the alternate entrance, which allows cavers to skip the tube.

“It wouldn’t be high adventure if someone didn’t chicken out,” Wuest says. He admits thatthe beginning of this enhanced excursion is what some guests find the most difficult. Then he cranks the winch, and down I go.

The cavers who discovered this section of the caverns in 1968 first used this shaft. It’s a tight squeeze, to say the least. And it gets dark pretty quickly. As I descend further, the light from above shrinks until it’s just a pinprick. I switch on my headlamp and imagine what it must have felt like for those original explorers.

After a few minutes, a light appears below and the rich aroma of deep earth intensifies. I touch down inside a humid, well-lit cavern called the Cathedral Room. Natural rock formations shaped like copper-colored scoops of ice cream fill this subterranean space, providing the illusion of melting walls. Translucent minerals catch the light and gleam like diamonds. Water drips from above to form puddles of pure, naturally filtered rainwater.

When our party assembles, it also includes Brian Vauter (the cavern geologist) and Brett Kelley (our guide). With the light from our helmets to guide us, we trudge deeper into the cavern while Kelley points out stunning dripstone formations. Stalactites hang like giant icicles from the cavern ceiling; thick, conical stalagmites rear up from the limestone floor into rounded tips. Mineral deposits, fissures, and watermarks from the distant past stripe the cave walls.

We follow a mudslick path into a deep pocket of darkness called the Ball Room. Slender, hollow formations called soda straws grow from the ceiling. Limestone outcroppings perch from the walls like gargoyles. When we arrive at a sharp drop-off, we must rappel down similarly rocky walls into Box Canyon. While carefully picking my way down, I comment that this huge cave would have made a perfect cowboy hideout. But Wuest says they’ve found no evidence that people or other mammals have ever lived here. Even insects appear to be scarce.

When the group stops for a water break, Vauter provides a quick geology lesson, estimating that the limestone that surrounds us originally formed about 140 million years ago. Groundwater passed through the soil and slowly—ever so slowly—ate through the limestone to carve the cavern. “The cave we’re standing in is roughly 12 million years old,” he says.

Time feels like it’s standing still here, but that’s not quite .accurate. Things happen slowly underground. Formations in this “living cave” grow about a cubic inch every century from the dripping water and calcite, a pace to make glaciers seem speedy.

We crawl like contortionists through a narrow pass and into the Fault Room, so named because an earthquake faultline allowed water to form this enormous cavern with vaulted ceilings. We stand 230 feet below the earth’s surface; amazingly, the temperature remains a constant 70 degrees here. Kelley points up to a 14-foot soda straw, the third-longest in North America. I also learn the caverns offer more than spectacular visual attractions.

“You’re sitting on a potentially significant climactic library for this part of Texas,” says Vauter. “By taking samples of the flowstone, we can examine the climate from tens of thousands—even hundreds of thousands—of years ago. Caves like this are a wealth of information.”

On cue, we shut off our headlamps. This complete absence of light, while calm and soothing at first, begins to feel thick, heavy, isolating. And it feels like it could last forever. After lighting back up, I ask Vauter if caves are a resource for our future. He tells me that pharmaceutical companies suspect cave-dwelling organisms might be the key to medical advances, and then he reveals that robotic probes for space travel are first tested inside caves. If they can successfully navigate and explore Earth’s more challenging terrain, he says, they should be able to do the same someday on a distant planet.

As for today, it’s time to crawl, climb, and hike the 1.25 miles back to the surface. The round-trip excursion lasts about three hours, and it leaves my clothes dirty and my muscles taxed. Back in the Texas sunlight, we wash million-year-old mud from our boots. The water carries it away into the topsoil, and I wonder how long it will take before it makes its way back into the caverns.