Illustration by Sara D’Eugenio/background via istock/benz190

Dust flies up from the wheels of Mark Walls’ UTV on a hot mid-September morning as he drives through the 300 acres of pecan trees that his granddad, a bespectacled dentist named Edmund “Doc” Darilek, planted in Seguin in 1958. The town, roughly 40 miles northeast of San Antonio, bills itself as the “Pecan Capital of Texas,” and Darilek was a founding father of sorts: In the 1960s, he installed a 1,000-pound concrete pecan beside its courthouse and helped orchestrate its first Pecan Festival. Walls’ mother, Sarah Darilek, was crowned Pecan Queen.

That legacy is on Walls’ mind as he drives. Pecans pop beneath the tires, but they aren’t supposed to be on the ground this time of year. Once a week over the summer at his farm 38 Pecans, Walls filled up a 300-gallon tank on his trailer to water his 80 youngest trees. But it wasn’t enough to get them through the summer’s crushing drought. Nearly half his young trees, plus 61 mature ones, have died. Here and there, jumbled stacks of felled wood await clearing–each the remnant of a tree that didn’t make it. “It makes me sick,” Walls says.

An estimated 100,000 acres of pecan trees—Texas’ official tree since 1919—cover the state. Harvest begins in late September and continues through Thanksgiving, when Texans sit down to a feast that often ends with the corn syrup-baked confection that is pecan pie (the official state dessert, of course).

Two years of severe drought, exacerbated by record-breaking heat, have stressed Texas’ pecan orchards. While a good state-wide crop weighs in at around 50 million pounds, last year’s was just 25.5 million pounds—the smallest harvest in more than a decade. And this season may not be much better, says Larry Don Womack, who owns Womack Nursery in De Leon and chairs the American Pecan Council.

“There are dead trees all over this state because of the drought,” Womack says near the end of September.

In a Nutshell

Though crops aren’t looking promising for Texas pecan farmers this year, you can still indulge in the state nut locally. Here are a few Texas pecan businesses you can visit or order from this holiday season.

38 Farms, Seguin

Founded in 1958, this pecan farm sells baking blends, pecan honey butter, samplers, and spiced jalapeño pecans.

The Pecan Shed, Charlie

From whole pecans to nutty coffee grounds, this family-owned business makes products using nuts from its orchard in Charlie. Visit its gift shops in Wichita Falls or Henrietta to get a sweet treat or other unique trinkets.

Comal Pecan Farm, New Braunfels

For five generations, the Friesenhahns have run this pecan orchard. Visit the store, located directly on the farm, and grab some honey roasted pecans or jalapeño pecan brittle. If you need to whip up a dessert in a hurry, try their pecan pie in a jar.

Pick Your Own Pecans, Kennedale

At this 21-acre farm in North Texas, visitors are invited to pick their own pecans and pay by the pound.

Boykin Farms, Falfurrias

This South Texas farm has a long and varied history but has sold pecans since 1990. It doesn’t just offer pecans by the pound—customers can purchase and take home an entire pecan tree.

Womack is among those who have been hit the hardest, having lost 10% of the 6,000 trees in the 200-acre orchard he leases about 100 miles northwest of Waco. With no water source for irrigation, the farm is at the mercy of the weather. A satisfactory year brings 28 inches of rain and 900 pounds per acre of fruit. But after 90 days without a drop, he expects to get less than 100 pounds per acre. “This is absolutely one of the toughest years ever,” he says.

In the 20th century, pecan farmers endured at least one serious drought every decade, the worst lasting seven years, from 1950 to 1957–back when threshing crews were still whacking nuts out of trees with cane poles. But they appear to be getting worse. Data from the Palmer Drought Severity Index have shown that by some measures, the 1950s drought wasn’t as severe as the one that wrecked Texas between 2010 and 2015, killing over 300 million trees. Farmers say there are similarities between the latter drought and now. “I think [this year’s] is equal [to it] or a little worse,” Womack says.

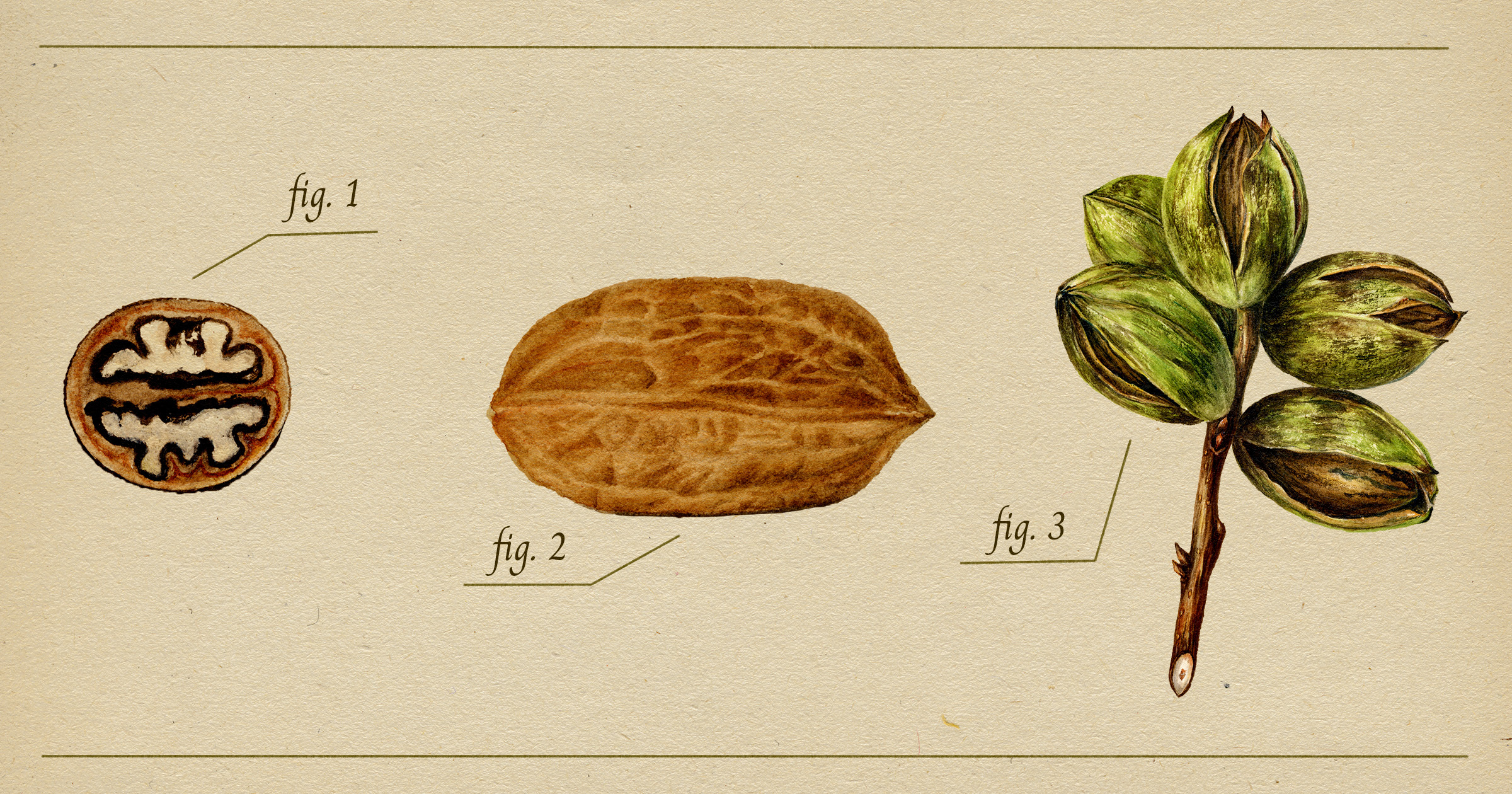

It’s bad news for pecans trees, which are native to Texas and can tolerate extreme heat so long as they have water. About 55 inches is ideal, says Larry Stein, a horticulturist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center in Uvalde. Without it, leaves fade and yellow. Limbs die. Nuts drop prematurely, or their shucks grow hard and refuse to open. “You can’t get the nut out,” Stein says.

Jake Montz tried to stave off the damage before it arrived. Montz is president of the Texas Pecan Growers Association and owns a 1,500-acre farm of 50,000 trees in Charlie, northeast of Wichita Falls. In July, after a heat dome rolled in, he sent out his tree shaker, which does exactly what its name suggests. About half the fruit rained down, giving what remained a better chance of making it to harvest. Though the nuts will be smaller, they’ll be tasty.

He isn’t expecting a much better harvest in 2024, since it can take a few years for stressed trees to bounce back. “Trees need to be in really good condition going into the fall to have a crop the following year,” he says.

Despite the crummy past two years, the pecan farmers who Texas Highways spoke with remain hopeful about the future, many believing the extreme weather is part of a natural cycle and won’t hang around forever. Climate scientists, on the other hand, predict the future is only getting hotter. In 2018, researchers at Texas Tech University found that warming oceans will strengthen the high-pressure heat domes that repel rain as they travel from the Gulf of Mexico to Texas in summer. Texas’ state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon has warned that the late 21st century could bring a multi-decade “megadrought” worse than any seen in the last thousand years.

But whatever their concern is over the weather, pecan farmers are all uneasy about the future of their water. Historically, farms with extensive irrigation have been able to survive and even thrive amid the drought. But as rivers, lakes, and aquifers shrink, they grow less reliable. Womack points out that Proctor Lake, which supplies water to many farms in his area, is now holding just 24% of its capacity, and farmers have been asked to cut back usage by 30%.

Stein says this could pose a serious threat to the industry. “My fear is that someday there is going to be a movement that says water is too valuable to use on pecans,” he says.

Even those who escaped the impact of this year’s drought aren’t taking it for granted. Belding Farms in Fort Stockton is the state’s second-largest producer of pecans, and like many farms in West Texas (which are set up with extensive irrigation to handle dry conditions), it’s had a good year. Still, its owners have petitioned the local groundwater authority to tighten rules surrounding how much water can be pumped from the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer, which supplies half its water. It’s also working to install low-evaporation sprinklers throughout the orchard. “We want to be prepared for what the future brings as best as we can, and the way to do that is to use less water,” says farm manager Zachary Swick.

Walls is thinking ahead, too. He’s now seeking state and federal funding to install water-efficient irrigation throughout his orchards. “We can thrive if we have the water,” he says. “This is my grandfather’s legacy, and I want it to be a part of my life.”