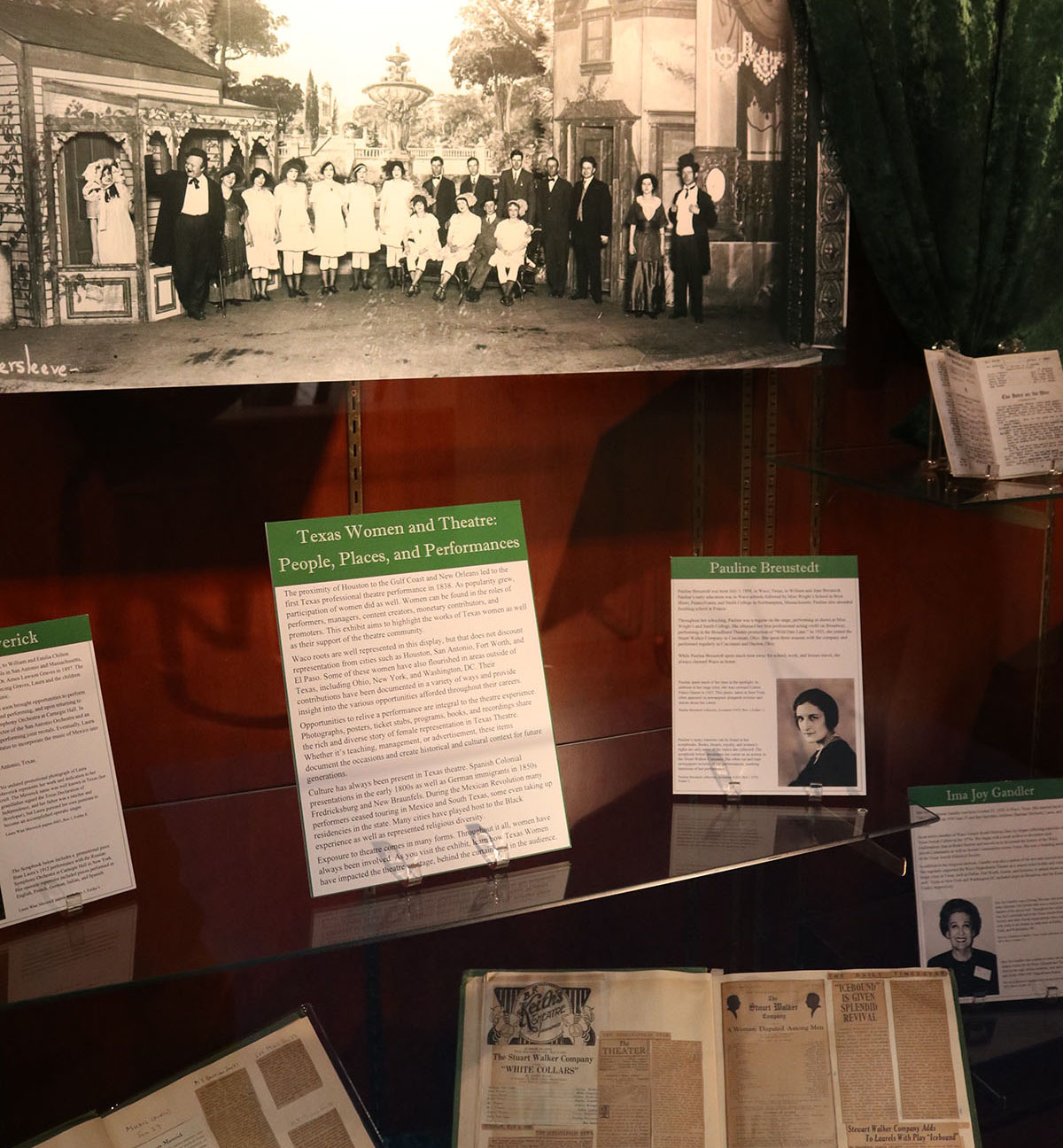

The Alamo Theatre Choir in Waco (top photo) represents one of the ways women contributed to theater in Texas. Photo courtesy of The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

Once described by a journalist as “a pint-sized whirlwind,” Waco theater manager and pianist Gussie Oscar was a force to be reckoned with. Born in 1875 in Calvert, where her family owned Casimir’s Opera House and Grand Hotel, she was arrested at least twice for opening the Waco Auditorium on Sundays—reportedly booking such “racy” acts as wrestling matches and chorus girls dressed in flapper outfits—in violation of the city’s Sunday closing laws. She also once served as the conductor of an all-female orchestra.

Oscar is one of the many intriguing female showbiz pioneers profiled in the exhibition Texas Women and Theatre: People, Places, and Performances. On view at the Texas Collection at Baylor University through May 31, it shines the spotlight on several female Texans who may be unknown for their contributions to theatrical arts.

“We wanted to show the diversity of women in Texas theater history not only culturally but also in terms of women who wrote, performed, directed, managed, and supported live performance in the state,” says Sylvia Hernandez, a Texas Collection archivist who co-curated the exhibit.

Along with photographs and audio recordings, the exhibit displays playbills, scrapbooks, programs, scripts, and other theater ephemera. All the materials on view are drawn from the collection’s expansive holdings, described in a university brochure as “the largest collection of Texana in the United States.”

When it comes to the diversity of the performers, you can start with Doris Goodrich Jones, aka the “Waco Puppet Lady.” She’s represented with four audio recordings of her puppet shows and her handmade puppet of prolific German sculptor Elisabet Ney, who lived most of her life in Austin. Jones, who was born in Temple in 1902, toured throughout Texas presenting marionette performances for which she did it all: the voices, sound effects, movements, and music. As the little dog Kickapoo says in Jones’ playlet Making Friends, “I know everything.”

Then there’s mezzo-contralto Laura W. Maverick. Described as “one of the first performing artists of her status to incorporate Mexican music into her repertoire,” Maverick was born into a storied San Antonio family in 1878. Her grandfather, Samuel Maverick, signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. A large promotional poster on view in the exhibition was created and distributed by her New York management company after her acclaimed Carnegie Hall performance of 1912.

One of the most powerful women in Houston theater was actress, educator, and director Nina Vance, who sent out 214 penny postcards in 1947, soliciting responses from people interested in starting a new theater. More than 100 theater-lovers answered the call, giving birth to the Alley Theater. Vance is represented in the exhibition with the programs for two productions that she directed, Rudolf Wilhelm Besier’s The Barretts of Wimpole Street and Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth.

In the early 1930s, playwright Annie K. Randle became one of the first Black students at Baylor. After moving to Waco with her family at age 19 in 1906, she attended Central Texas College and was introduced to theater. Later in her life, she was chosen to attend Baylor, where she learned more about professional theater. She went on to teach drama in local schools and write plays such as The Voice of the Wire and The Blood Calls Out. A program for a production of the first title is included in the exhibition.

Erma Lewis was another influential Black contributor. Her story is presented in a book on Black performance in the state called Stages of Struggle and Celebration: A Production History of Black Theatre in Texas by Sandra M. Mayo and Elvin Holt. She founded the Sojourner Truth Players in Fort Worth in 1972, and until her death a decade later, she produced many well-known dramas on the Black experience for Cowtown audiences.

Throughout the exhibit are interesting items that resonate with audiences today. A program for a 1917 recital in Marlin that featured soprano Naomi Ruth Cobb of Waco and her soon-to-be-famous nephew, the baritone Julius L. Cobb “Jules” Bledsoe, cautioned: “Perfect quiet is requested of the audience during the numbers.” The past’s version of “turn off your cellphone.”

One small section of the exhibition goes into the Mexican Revolution that started in 1910 and how it spurred many performers to migrate north of the Rio Grande. Books about Mexican American theater history offer visuals and information about such institutions as La Compania Villalongin of San Antonio and El Teatro Colon of El Paso.

Founded in Nuevo Leon in the late 1840s, the family troupe La Compania Villalongin occasionally performed north of the border before establishing a residency in the Alamo City in 1911. Out in West Texas, El Teatro Colon opened in 1919, with offerings that included live performances by silent film actress Mimí Derba, concerts by the orchestra of Lerdo de Tejada, and the 1919 film about a 1915 true-crime wave in Mexico City, El automovil gris.

For hints about how far American—and Texan—culture has come, all you need to do is look at two illustrations in a souvenir booklet for Houston’s 1910 Majestic Theatre. The first shows a “Men’s Smoking Room,” while the other one depicts a “Nursery and Ladies Retiring Room on the Promenade Floor.” The latter is described as “essential to the pleasure and convenience of the fair sex and the children.”

Illuminating and revelatory, these little-known stories about the female contributors to Texas theater might inspire some budding historian or archivist to create a second act on the subject. Or it might inspire a young woman to believe that she, like Gussie Oscar or Nina Vance, can find her own place in Texas theater history. If so, I’ll be in line to buy a ticket.

The Texas Collection is located in the Carroll Library, at Fifth and Speight streets on the campus of Baylor University. More information can be found here.