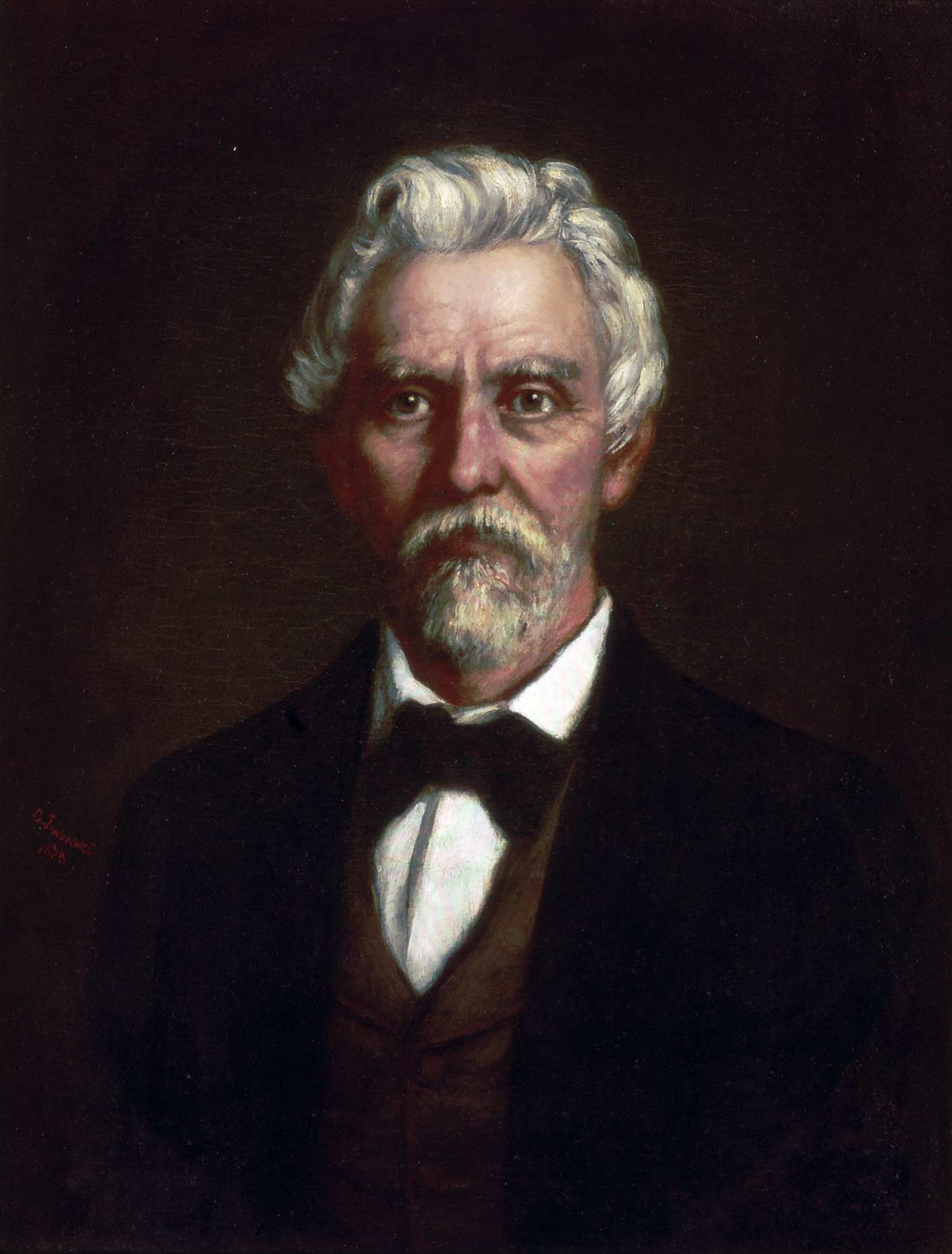

Sam Maverick, pictured in this 1873 painting by Carl G. von Iwonski at The Witte Museum in San Antonio, moved to Texas in 1835. Photo: Courtesy of the Witte Museum, San Antonio, Texas

Deep down, every true Texan wants to be a maverick. Whether your folks have been here for centuries or you just arrived this morning, a disposition to be different from the herd—to mosey through life unbranded—slips into your psyche on Lone Star soil.

For that, we can thank Samuel Augustus Maverick. A native of South Carolina, Sam arrived in San Antonio as a 32-year-old lawyer and land speculator in September 1835. He’d been sent by his father to manage a family plantation in Alabama when he decided he’d rather be “gone to Texas.”

Learn More

Maverick arrived at an influential time—he signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and served in the Texas Legislature and as San Antonio mayor. His wife, Mary, started the family’s tradition of historical preservation, and her book, Memoirs of Mary A. Maverick, is one of the best TRUE TX accounts we have of pioneer Texas. And the couple’s many descendants—six of their 10 children grew to adulthood— continue to shape the Alamo City’s cultural landscape.

“Sam loved San Antonio from the moment he first saw it,” says Lewis F. Fisher, author of the 2017 book MAVERICK— The American Name That Became a Legend. “It’s true,” adds Paula Mitchell Marks, author of the 1989 biography of Mary and Sam, Turn Your Eyes Toward Texas. “Something in him responded strongly to the pleasantly foreign antiquity of its Spanish churches and homes.”

When Sam first came to San Antonio in 1835, however, tensions were mounting between revolution-minded Texians and the Mexican government. Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos arrived in San Antonio with 700 soldados and placed Maverick under house arrest to prevent him from joining some 400 Texian rebels camped outside town.

Released by Cos on Dec. 1, Maverick joined the Texians in the four-day Siege of Bexar. At the siege’s conclusion, Cos surrendered in a small adobe that came to be known as the Cos House, which now serves as an event venue near the San Antonio River.

Sam Maverick arrived at an influential time—he signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and served in the Texas Legislature and as San Antonio mayor. His wife, Mary, started the family’s tradition of historical preservation, and the couple’s many descendants continue to shape the Alamo City’s cultural landscape.

Maverick and the other Texians proceeded to hole up in the Alamo, suspecting Santa Anna and a much larger force were on the way. Santa Anna’s troops famously besieged the Alamo for 13 days before the final bloody assault on March 6. But Maverick had already left four days before the attack because he was elected to represent San Antonio at the Convention of 1836. Meeting at the Brazos River town of Washington, Maverick and his fellow revolutionary delegates declared Texas’ independence and adopted the territory’s first constitution.

Falling ill after signing the declaration, Maverick headed east to recuperate and tend to family business in Alabama and South Carolina. Along the way, he met and married 18-year-old Mary Ann Adams of Alabama. After the couple’s return to San Antonio in early 1838 with young Sam Jr. in tow, Maverick often traveled away from the family, surveying and buying land in unsettled parts of the young republic. Eventually, he owned some 300,000 acres in Texas.

In the mid-1840s, fears that Mexico would reinvade San Antonio prompted the Mavericks to move to Matagorda Peninsula on the coast—and there the family name became a legend.

The true story is a simple one, and the fact that it raises the unsettling issue of slavery perhaps accounts for some of the subsequent mangling of the truth. The truth—as recounted in the history books by Fisher and Marks—is that Maverick left a slave named Jack with little wrangling experience in charge of a herd of cattle. The cattle wandered, unbranded, and in time, as stories traveled by wordof- mouth through cow camps and saloons, and as accounts appeared in newspapers and sources like Charles Siringo’s 1885 book, A Texas Cowboy, or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony, such an animal became known as a “maverick.”

In MAVERICK, Fisher tracks the term up the cattle trails and beyond, all the way to James Garner’s TV Western of the 1950s and ’60s, a Ford muscle car, and John McCain’s presidential campaign. Along the way he identifies a series of misconceptions about the word’s origin. Some accused Maverick of cattle thievery. Even the esteemed columnist William Safire repeated slanderous misinformation about Sam and his bovine misfortune.

Back in San Antonio in the mid- 19th century, the Mavericks moved from their house on Main Plaza to a new home on the northwest corner of Alamo Plaza. By the time he died in 1870, Sam owned a large swath of land between the old mission and the river.

Curating the family’s and the city’s legacy, Mary became the first president of the Alamo Monument Association in 1879. Sam and Mary’s granddaughter Rena Maverick Green co-founded the San Antonio Conservation Society in 1924, working with preservationists to protect the Alamo and other colonial missions, the Spanish Governors Palace, and the San Antonio River.

Another of Sam and Mary’s grandchildren, Congressman Maury Maverick, co-sponsored the Historic Sites Act of 1935, the country’s first national preservation policy. Four years later, as San Antonio mayor, Maury secured federal funds for the restoration of La Villita, the historic downtown village with galleries, shops, and the Maverick Plaza for concerts and events.

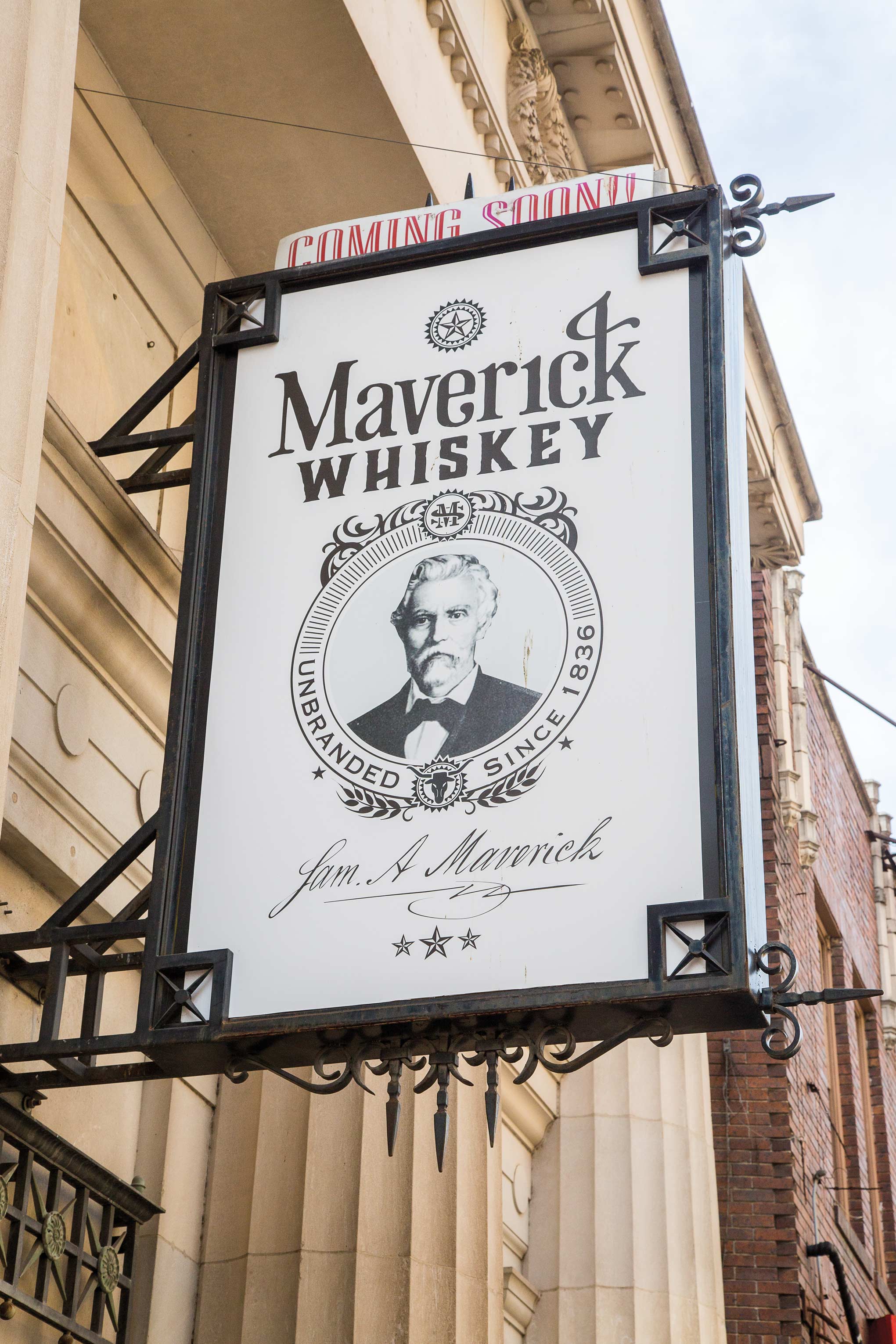

Descendant Ken Maverick is opening a whiskey distillery on Broadway Street in San Antonio.

The family name also lives on in a new downtown business, Maverick Whiskey, which is housed in the 1918 Classical-style former bank at 115 Broadway Street on land that was part of the family’s original homestead. A portrait of Sam graces the sign for the distillery and sippin’ parlor. Great-great-great-grandson Ken Maverick is planning a soft opening for late this summer. “Sam liked to close land deals with a bottle of commemorative whiskey,” Ken says, and according to family lore, “he left a small barrel in the Alamo when he left for Washingtonon- the-Brazos.” Family history also holds that one supply of Sam’s whiskey, shipped to a port on Lavaca Bay, was ransacked by Comanches in the infamous Linnville Raid of 1840. Ken says a small museum in his new distillery will chronicle such Maverick family history.

The 1893 Maverick-Carter House.

The Mavericks’ legacy can also be found on the northern edge of downtown San Antonio at the Maverick- Carter House. Built for Sam and Mary’s son William in 1893, H.C. and Aline Carter bought the home in 1914. Aline, who served as Texas poet laureate in 1947, installed a private chapel in the home’s library and an astronomical observatory on the roof. Still owned by the Carter family, the house hosts artistic and scientific programs, such as poetry readings.

Lower-case “mavericks” also remember the term’s namesake—from restaurants across the country to sports teams, summer camps, motorcycle dealerships, and even a British magazine devoted to folk and roots music. Just this year, the new Maverick Texas Brasserie opened in San Antonio’s Southtown arts district featuring a menu that ranges from French cuisine to burgers.

It’s clear that San Antonio—and all Texas—is in no danger of un-mavericking anytime soon. Maury Maverick’s granddaughter Fontaine Maverick even went to court “after a couple divorces” to legally reclaim the storied surname. Fontaine’s 92-year-old mother, Terrellita Maverick, often described as one of the most maverick of the Mavericks, puts it best. “If you’re unbranded, in charge of your own self, and wild and free, then sister you’re a maverick!”

Texas Mavericks

In May 1848, at the mouth of Las Moras Creek on the Rio Grande, Sam Maverick wrote to his wife, Mary, that it was “one of the prettiest spots on earth.” Eight years later, the location became part of newly created Maverick County. To this day, across Texas, all breeds of businesses, places, and things are named for the legendary Texas forefather.

Folks at Alpine’s Maverick Inn say their motel is the place to “experience the true spirit of far West Texas.” The Maverick Ranch RV Park in Lajitas invites mavericks to stay “where the stars shine brighter in the night sky than anyplace on earth.” True Texas fare awaits at Maverick Grill eateries in Santo, Arlington, and Floresville.

The Dallas Mavericks won the 2011 NBA championship by playing the maverick way. The Guitar Maverick shop in Keller knows that Texas musicians don’t follow the herd. And Maverick Western Wear in the Fort Worth Stockyards resides in a 1905 building that has housed various businesses over the years, all known by the name Maverick.

Perhaps the most maverick part of the state, Big Bend National Park, named a 14-mile unpaved route past the Terlingua badlands to the Rio Grande “Old Maverick Road.” Talk about unbranded.