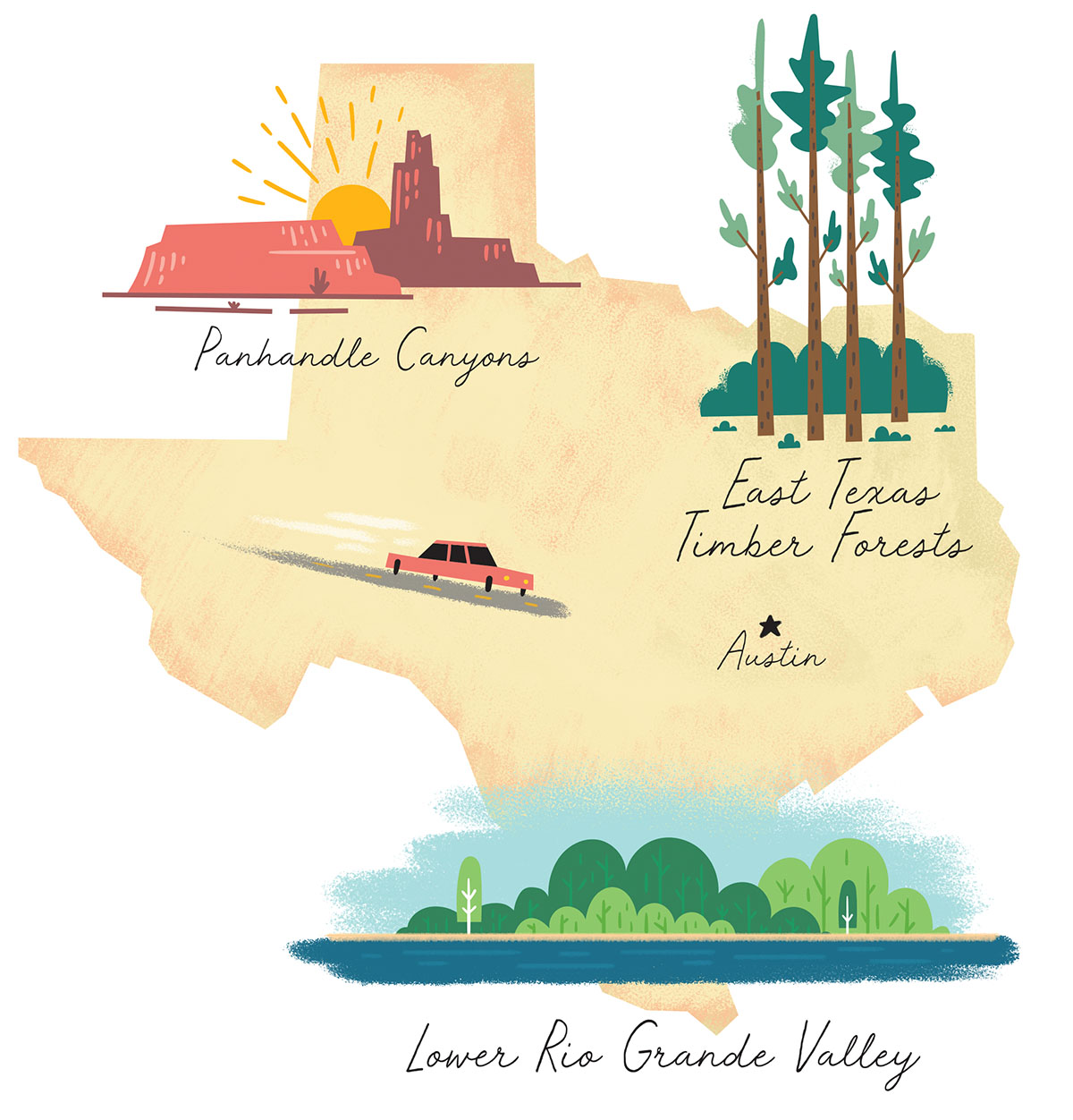

A self-care trip through

the parks of Texas

By Asher Elbein

Illustration by Shawn Nielsen

The pale light of a summer morning crept in between canopies of sweetgum and water oak, casting dappled shadows over the paths of Big Thicket National Preserve. Beyond a shuttered visitor center, the Kirby Nature Trail wound through baygall thickets and flooded cypress sloughs, through explosions of ferns and piles of decaying logs. The air pressed in like wet velvet, heavy with pollen and leaf mold.

I’d come to the Big Thicket because, on this August day, American civil society felt like it was splitting at the seams. A viral pandemic had killed 100,000 people; a month later, the number would double. Swaths of the population had spent months cooped up at home, juggling parenting with their jobs, or venturing to workplaces fraught with new dangers. The economy had taken its worst hit since the Great Depression, and the nation’s political discourse was in tatters.

I’d been feeling a restless desire to escape the world—and a contradictory yearning to immerse myself in it. I was also curious about how Texas’ public lands were faring in an unprecedented time of quarantine shutdowns and surging interest in outdoor recreation. So, I decided to hit the road, plotting a route from the timber forests of East Texas, to the coastal plains of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, to the Panhandle canyons where the bison roam. The wilderness called to me, offering isolation and meditation. But what would I find?

Illustrations by Shaw Nielsen

I was not alone in my urge to escape. According to a survey conducted in June by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the percentage of adults reporting mental health conditions like depression and anxiety had risen to 41%—double the pre-pandemic rate. The nation continues to face a crushing amount of stress. “A disaster like a hurricane comes and goes, and people know that it’s over now,” said Lokesh Shahani, a psychiatrist at McGovern Medical School, part of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “Our first case of COVID was somewhere back in April, and we’re still dealing with it.”

Many people have coped with it by going outside. While there is no precise study of how many Americans have visited parks since March, my casual poll of friends and acquaintances found a sharp uptick. One friend, Eva Sadler, of Austin, went to just three parks in Texas in 2019. But since quarantine started, she and her husband have visited 10 parks and camped at four, venturing to places both near—Enchanted Rock State Natural Area—and far off—Monahans Sandhills State Park, 370 miles from Austin. State parks in Texas closed briefly in the early days of the pandemic, but they have since reopened at 75% capacity with safety measures in place. Online reservations are encouraged; many ranger-led programs are on hold; and some visitor centers are closed. Texas State Parks Director Rodney Franklin said the system’s total visitation numbers are down due to the visitor caps, but generally parks have seen a sort of perpetual spring break, with numbers holding steady during the week as well as the weekend.

Anecdotal evidence shows quite a few of these visitors are new. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s customer service center has fielded an increase in calls from people who’ve never been to a state park and are curious about where they should visit, Franklin said. “This pandemic has been rough on everybody,” he said. “But it has given folks an opportunity to find a new way to enjoy time outside. Folks who’ve never been to a state park will potentially see how cool they are, and see how they’re great places to visit. And maybe when this is all behind us, they’ll continue to be visitors and supporters of state parks moving forward.”

The Sadlers have tried to make the most of the situation. Though they’ve visited state parks before, the anxieties of quarantine motivated them to get outside more. “There’s a complete and total difference between sitting in your home, quarantined, and then going out to Enchanted Rock and being able to see the Milky Way and shooting stars,” Eva said. “It reorganizes my body and my brain in a way.”

Shahani said there’s ample evidence that exposure to wilderness can be soothing to body and soul: Research has shown that going out into green spaces is linked to better stress regulation, decreased cortisol levels, and increased mental health.

Society’s newfound interest in parks is more than our simple desire for a break, however. This spring, as the pandemic struck, a rash of feel-good stories spread on social media—wishful accounts of wilderness creeping back into quiet cities, of animals reclaiming abandoned streets and thriving in empty parks. Such stories were overblown, according to park officials I spoke with. But the rumors showed a hunger for an often undervalued human need: to be still and watch the rhythms of the world around us. Because of the pandemic, many of us have been forced—by circumstance and stir-craziness—to pay attention to nature.

Simply being outside in greenery provides relief, but I wanted to take a more mindful approach. Before getting on the road, I called Emma Scott, a resident of Conroe who serves as a “forest bathing” guide. She leads nature outings that draw on a Japanese therapy practice of experiencing nature through the senses. Scott walked me through the fundamentals: Move slowly, pay close attention to your senses, and keep yourself open to the world around you. “You don’t want to force it,” Scott said. “Just be in the space.”

Armed with Scott’s advice, I drove out to the Big Thicket in East Texas. The preserve sprawls in a series of discrete units around the town of Kountze, with multiple trailheads, day-use areas, and access points scattered throughout the region.

“We are very biologically diverse,” Big Thicket park ranger Megan Urban told me. “You can visit us in one of our units and see a roadrunner and prickly pear, and on the same day, visit another unit and see an alligator. It’s the easternmost part of some western plant and animal communities, and the westernmost range of species from the east. The biodiversity is phenomenal.”

Big Thicket has remained open throughout the pandemic, though its visitor center and bathrooms closed temporarily. Ranger-led programs have been canceled since March. None of this has significantly dissuaded visitors. The preserve reported a slight decrease in visitors during May (20,000), but visitation jumped to around 28,000 in June before settling into normal numbers of about 22,500 visitors per month for July and August.

I spent two days hiking in the Big Thicket, setting out in the early morning. On each jaunt, I focused for a time on a single sense; the slight rustles and chirps of the birds, the scent of mud and vegetation, the light shimmering on spiderwebs stretched taut across the trails. I saw a rat snake peering out of a leaning snag and an otter chasing trapped fish around the roots of a cypress in a drying pool. It would have been easy to miss all of this. I’m a fast walker, and sometimes I fall into autopilot. Forest bathing demands the opposite: to slow down, breathe through each step, and let the woods show you their secrets.

Move slowly, pay close attention to your senses, and keep yourself open to the world around you. “You don’t want to force it. Just be in the space.”

From the Big Thicket, I traveled south, through the rich pasturelands of the Texas Gulf Coast, to the 110,000-acre Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge near Brownsville. I had hopes of glimpsing an ocelot, one of the elusive spotted cats that inhabit the park. Though I had the trails to myself, the refuge wasn’t empty. I saw cyclists on the roads and cars in the parking lots. According to ranger Chris Quezada, the refuge’s attendance dropped in the spring but had been steady during the summer with around 30 visitors on weekdays and up to 200 on weekends.

I spent two afternoons wandering the refuge, keeping a running count of roadrunners and rabbits that scampered out of my way. The breeze was heavy with salt from Bahia Grande, and butterflies floated like scraps of colorful paper over the tall grass. I spent one magical morning sitting in a bird blind near the visitor center, watching chachalaca birds, orioles, and green jays scold an immense indigo snake drinking from their birdbath. The ocelots, true to their reputation, kept hidden.

I left Laguna Atascosa and headed north to the final stop on my road trip, Caprock Canyons State Park. The drive took me across the Hill Country, where the limestone hills fell away and the sky grew until I sped through rolling open plains dotted with weathered towns. Located near the bottom of the Panhandle, where the plains meet the Caprock escarpment, Caprock Canyons State Park harbors a spiderweb of ravines and bottomlands covered in juniper and scrub oak.

The cap on state park visitors has helped prevent the park from getting overwhelmed, but it has been busy nevertheless. “We usually have a slow July and August, and it has not slowed down,” Park Superintendent Donald Beard said. The park has also seen slightly higher numbers of vandalism incidents and reports of heat exhaustion. Such complications are to be expected, Beard said; it comes with having new visitors.

“A lot of people who are coming are not our regular users, and a lot of them are new to state parks in general,” he said. “They’re just looking for a place to get out and get away, and state parks are a great opportunity for that.”

Caprock Canyons’ campsites were indeed full of tents and RVs during my visit. But when I started out on the South Prong Trail one morning before sunrise, it felt as if I had the park to myself. There was no sound but the sighing of wind and the insistent buzz of horseflies. As the trail zigzagged sharply up a cliffside, I crawled on all fours, bands of sandstone smooth beneath my fingers. Then the trail dropped back down into the canyons by narrow turns, trees shrinking and growing sparse, until I walked out on broken red hills beneath the sun.

HOW TO VISIT PARKS SAFELY

Make reservations online: Almost all state parks are open with limited capacity. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department recommends making advance reservations on its website, tpwd.texas.gov. Walk-up entry is allowed, but with the attendance restrictions, many parks may be booked up. National parks, preserves, and wildlife refuges are also open, at least in limited capacity. Most don’t require advance reservations.

Plan for shared spaces: Most park restrooms are open, but it’s a good idea to bring along your own soap and hand sanitizer. If you’re going to be making use of picnic tables, consider bringing a table cover. And remember to always wear a mask and maintain a safe distance from other visitors, especially indoors.

Hit the trails early and walk quietly: For the best chance of seeing wildlife, try to be out on the trails by sunrise, or go out around sunset. Know your limits and carry plenty of water.

Respect the space: Parks are shared landscapes. Dispose of all trash in appropriate receptacles. Don’t collect rocks or vegetation, which are legally protected, and don’t hassle wild animals.

The bison never broke stride, continuing on past me, shaggy and compact with muscle, its eyes steady and soulful.

It was here that I met the bison. The Texas State Bison Herd—the only remaining herd of Southern Plains bison living wild on public land—is Caprock Canyons’ claim to fame. This one was wandering alone when I rounded the corner to see it walking toward me. Multiple signs posted around the park remind visitors that bison are wild, territorial, and not prone to forgiveness. I backed up as slowly and deferentially as I could, retreating into the vegetation off the trail. The bison never broke stride, continuing on past me, shaggy and compact with muscle, its eyes steady and soulful in its curly-haired face. I watched the ripples of its skin under dancing flies, heard the crunch of hooves on sand. Then it was gone.

This was the experience I’d been hungering for during the months of quarantining in my house. More than exercise, more than a desire for wide-open spaces, I wanted to encounter creatures living a life far removed from my own.

While some parks have shortened their hours and others have limited their services, the natural relief we all crave still awaits our discovery. In comforting contrast to the transient troubles of our society, these wilderness refuges and parks steadily hum their own ancient rhythms.