The 1920s was an exciting decade for American aviation: Barnstormers flew from town to town showing off their daredevil tricks; pioneering pilots set speed and distance records, then quickly broke them; and some of the first passenger airlines tested the skies. Perhaps the greatest achievement of the decade occurred in 1927, when Charles Lindbergh made his solo, non-stop flight across the Atlantic. Young Victor Stanzel of Schulenburg grew up during this golden era of aviation, and that’s when his own ambitions began to take flight.

Victor, a farm boy whose Austrian grandparents immigrated to the Schulenburg area in the 1870s, started carving balsawood into replica airplanes as a youngster, inspired by the San Antonio-based military airplanes that flew training missions over the area. Equipped with drafting and machine-shop training acquired through correspondence courses, Victor began manufacturing model plane construction kits to sell by mail order in the 1930s. His brother, Joe, joined the project, and their fledgling business, the Victor Stanzel Company, would last nearly three-quarters of a century and help put the tiny South Texas town of Schulenburg on the international map.

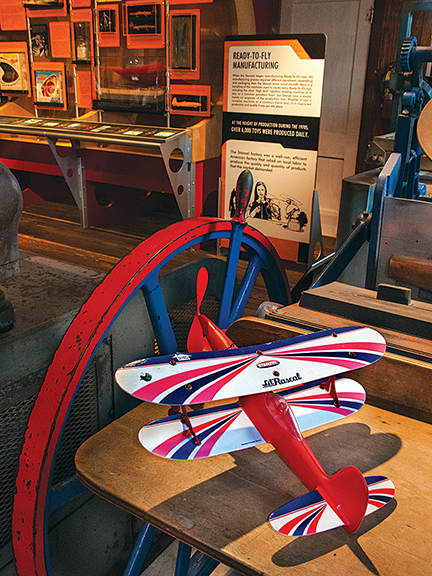

Today, the Stanzel Model Aircraft Museum honors the legacy of the brothers, both of whom passed away in the 1990s. Opened in downtown Schulenburg in 1999—two years before the company closed in 2001—the museum displays many of the Stanzels’ 47 different model and toy aircraft, including early, true-scale models like the Curtis Hawk P-6-E; the Tiger Shark, which was the first gas-powered guide-line plane kit (the operator flew the model with a line connecting the controller and the plane); and various “ready-to-fly” toy planes. The exhibit also includes blueprints, photographs, and other artifacts from the Stanzels’ own personal history of flight.

Eugenia Reeves, the museum’s manager, estimates that about 3,500 visitors, including school groups and hobbyists, find their way to the museum each year. “We get a lot of pilots and other retired service people, as well as international travelers,” she says, “because the Stanzels sold to hobby shops all over the country and the world.”

As the museum’s exhibits explain, the brothers’ entrepreneurial and engineering accomplishments weren’t limited to model and toy planes. They invented and built amusement park thrill rides like the “Stratos-Ship,” an electric motor-powered, six-passenger rotating and revolving rocket ride, which they introduced at the 1936 Texas Centennial in Dallas. They also manufactured various toys, most of which had something to do with flight, but also included several battery-powered racecars.

“They were mostly self-taught, and they worked hand-in-hand,” says Bob Stanzel, nephew of the Stanzel brothers. “Generally speaking, Victor was the idea guy, the visionary, who did a lot of the designs, and Joe was the implementer, figuring out how to execute the manufacturing. He was a genius at putting things together.”

Bob Stanzel is the president of the Stanzel Family Foundation, which funds the museum. His father, Reinhart, was the middle child between Victor and Joe, and later in his life, Reinhart joined his brothers at the factory. Bob remembers growing up in an environment of aviation and creativity. “The home that I was raised in was a block from the factory,” he says. “As a kid, I spent as much time down there as possible. I’m sure I annoyed them a bit. As I got older, I worked at the factory, as did a lot of the kids in the area, working on the production and assembly lines.”

In the factory wing of the museum, which is set in the original 1935 wood-framed workshop, visitors see some of the company’s woodcutting saws, planers, and a vacuum-forming machine used to manufacture plastic pieces. Models and plans of numerous planes, toys, and carnival rides are displayed in various stages of completion.

The third part of the museum, the Ancestral Residence, is the 1870 home of Franz and Rosina Stanzel, grandparents to the Stanzel brothers. It has been painstakingly restored to its original condition and furnished with 19th-Century antiques.

“I think the most important artifact or attraction in the museum, really, is the story,” Bob Stanzel says. “It’s a great American story about two farm boys who had a vision and made it happen. Early on, they just put their heads down and kept working, and in the latter part of their career they were inducted into the [Academy of Model Aeronautics] Hall of Fame. I think it made them proud that their peers understood and respected the quality of the work they did. I worked for Victor and Joe, and nothing left that factory unless it was perfect.”

A visit to the Stanzel Model Aircraft Museum demonstrates just how perfect the Stanzel brothers’ work was. Even on a diminutive scale, their ex-

pertise opened up the skies for generations of hobbyists and children who shared their passion for America’s high-flying ambitions.