When Galveston County historical preservationist Samuel Collins III gives presentations about local boxing legend Jack Johnson, he likes to offer a modern day reference: the 2018 blockbuster movie Black Panther.

Set in the fantasyland of Wakanda, Black Panther struck a chord with audiences seeking superheroes of African descent. It’s great to champion fictional heroes, Collins says, but everyday heroes also command attention. And Jack Johnson, who in 1908 became the first African American heavyweight champion of the world, transcended Jim Crow discrimination by living life on his own terms, paving the way for activists like Rosa Parks and Muhammad Ali to live more freely.

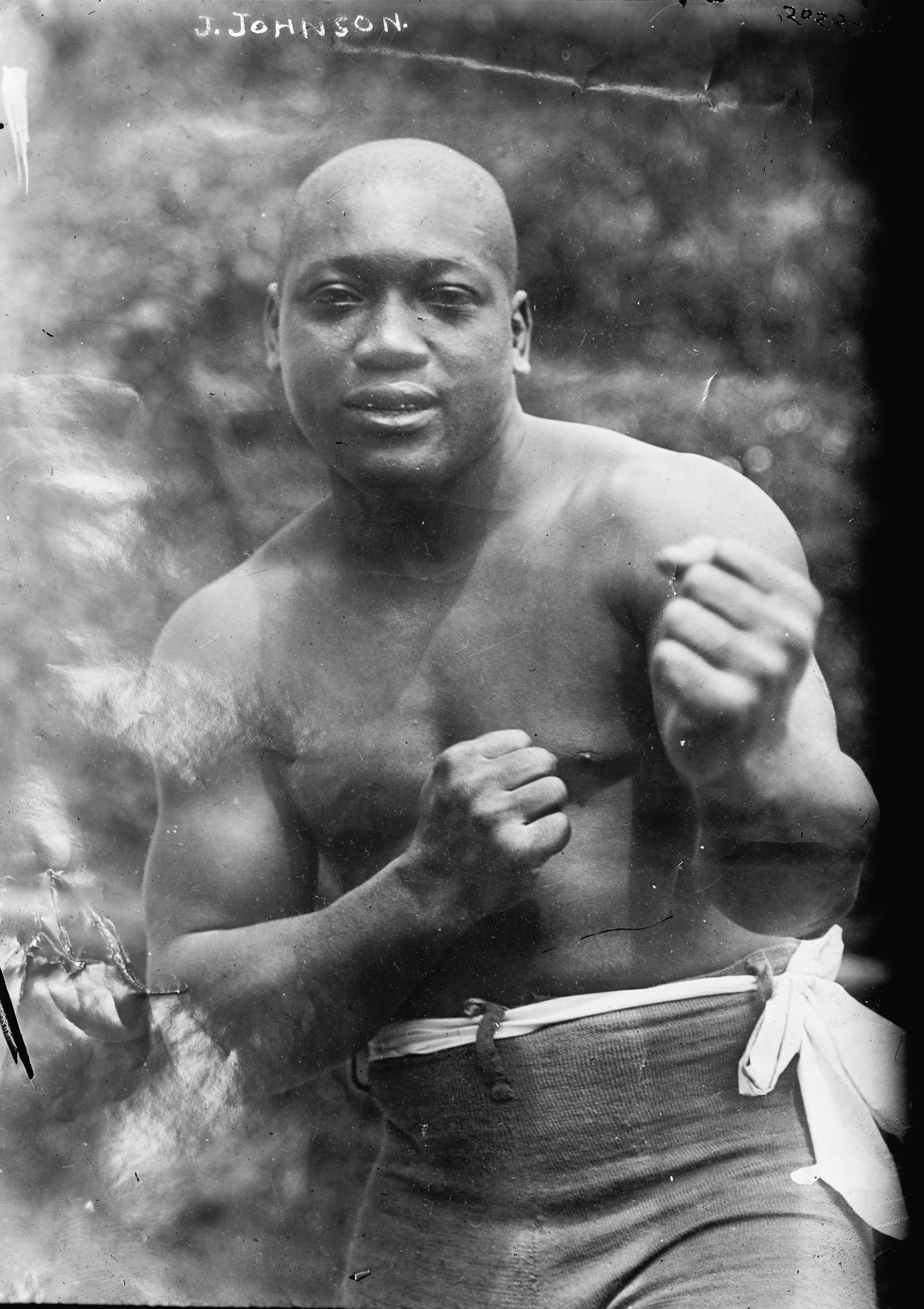

“Jack Johnson was a real person from a real place called Galveston,” Collins says while standing in his church clothes outside Old Central Cultural Center, formerly Central High School, the first black high school in Texas. In the park behind Old Central, located on Avenue M, a life-size bronze statue depicts Johnson in his prime: roughly 6 feet, 200 pounds, and ready to rumble.

The controversial story of Johnson, known as the Galveston Giant, continues to unfold more than 70 years after his death in 1946. In 1970, the movie The Great White Hope, loosely based on his life and the search for a white boxer to take him down, was released, starring James Earl Jones. And in 2005, Johnson got the Ken Burns treatment with Unforgivable Blackness, a documentary based on Geoffrey Ward’s biography of the same name.

The latest chapter in the Johnson saga was written just last year. In May 2018, President Donald Trump, prompted by Rocky star Sylvester Stallone, posthumously pardoned Johnson for his violation of the Mann Act more than 100 years prior. The act forbade transporting women across state lines “for immoral purposes.” In 1913, critics convicted Johnson for his relationship with Belle Schreiber, a white girlfriend who had worked as a prostitute. Upon sentencing, Johnson fled to Europe, South America, and Mexico for seven years but came back to the United States and served nearly a year in federal prison.

“Strength from Example”

The erasure of this perceived past transgression helps Galveston more comfortably embrace its most famous native son, an international icon despite the troubles he encountered in his home country. Not limited to boxing, he was also a bilingual world traveler, musician, writer, and inventor with a patent to his name.

“If kids could draw from the strength of his example of just wanting to be the best—black, white, yellow, red, brown—all kids, all people, can be inspired to be the best in their profession,” Collins says. “Jack Johnson was the best in the world. How many people can say they were the best in the world in anything that they did?”

The statue of Johnson at Old Central, installed for the November 2012 dedication of Jack Johnson Park, shows Johnson leaning forward, like he’s readying a punch. Austin sculptor Adrienne Isom, a student of acclaimed muralist John Biggers, won a competition for the commission.

“I don’t think a lot of people would have been so creatively defiant if ‘firsts’ such as Jack Johnson had not dared to step up and out,” Isom says. “Make no mistake about Jack Johnson: Every step he made in his life and the ring was carefully thought out and premeditated. He knew how daring his acts were and every consequence of his actions.”

Johnson came of age in Galveston. He was born on the island in 1878 to parents who were born into slavery. Johnson dropped out of school as a fifth-grader and worked odd jobs, including as a longshoreman. He traveled to Manhattan and Boston for a brief period, during which he befriended a boxer. When he returned to Galveston, he got into boxing and started fighting for money in about 1895.

“Make no mistake about Jack Johnson: Every step he made in his life and the ring was carefully thought out and premeditated. He knew how daring his acts were and every consequence of his actions.”

A turning point came in February 1901, when Johnson fought a white boxer named Joe Choynski in Galveston. Prizefighting was illegal in Texas then, and police arrested both men after Choynski’s third-round victory. But that turned out to be a good deal for Johnson because while they were in jail together, Choynski, an experienced boxer, mentored Johnson.

Johnson credited that experience with the development of the parrying skills that would become his hallmark. His style entailed deflecting an opponent’s punch and knocking him off balance, and then quickly countering.

“Johnson did things very few fighters do—defensive genius things,” explains Bob Spagnola, a local boxing expert. In 1985, Spagnola was part of a group that brought Muhammad Ali, Tommy Hearns, and “Sugar” Ray Leonard to Galveston to induct Johnson into the Houston Boxing Association Hall of Fame. “He would break these guys, hit ’em, stop them from doing things even as they were just beginning to start to think about doing them.”

Johnson Touchstones

Johnson’s independence and flamboyance stirred controversy among some African American contemporaries, including the scholar Booker T. Washington, who said of Johnson: “It is unfortunate that a man with money should use it in a way to injure his own people, in the eyes of those who are seeking to uplift his race and improve its conditions.” But Johnson has long had plenty of true believers, and Collins is among them.

Driving eastbound on Galveston’s Broadway Avenue, an island thoroughfare dotted with palm trees, Collins points out Ashton Villa, where an annual Juneteenth holiday celebration commemorates the significance of June 19, 1865, the day the U.S. Army officially notified Texans that slavery was dead (more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect). Just past that is Reedy Chapel, the first African Methodist Episcopal Church in Texas—and the Johnson family’s place of worship.

Collins pulls over at the 806-808 block of Broadway to look at the place where Johnson’s 1900 home once stood. His research points to an earlier residence in the 1880 census on 14th Street, but the original home is also gone. The Great Storm of 1900 wiped out many of the places that bore Johnson’s footprints.

On Sealy Street, E. Herron’s paintings of Johnson and other prominent black locals adorn the outside wall of the African American Museum, now closed to the public. Nearby, Jack Johnson Boulevard, formerly 41st Street, has honored the local boxer since 2002.

“Jack Johnson was the best in the world. How many people can say they were the best in the world in anything that they did?”

Collins’ next stop is the Oaks neighborhood, where in a residential cul-de-sac, a carving of Johnson emerges from the base of an oak tree ravaged in Hurricane Ike in 2008. Sculptor Earl Jones interpreted Johnson with his boxing gloves raised triumphantly above his head and his championship belt buckle gleaming, as if a real-life superhero emerging from the tree trunk.

Collins’ last stop is the Bryan Museum, a collection covering Texas and the American West, located in the historic Galveston Orphans Home. Collins, a member of the museum’s board, once owned a painting of Johnson by the artist Eddie Filer, but in need of cash to help pay for his daughter’s college tuition, he sold it to the museum. The painting, part of a museum collection that includes two tobacco collectors’ cards featuring Johnson, shows Johnson in various boxing stances and in a fight against Jim Jeffries, aka “the Great White Hope.”

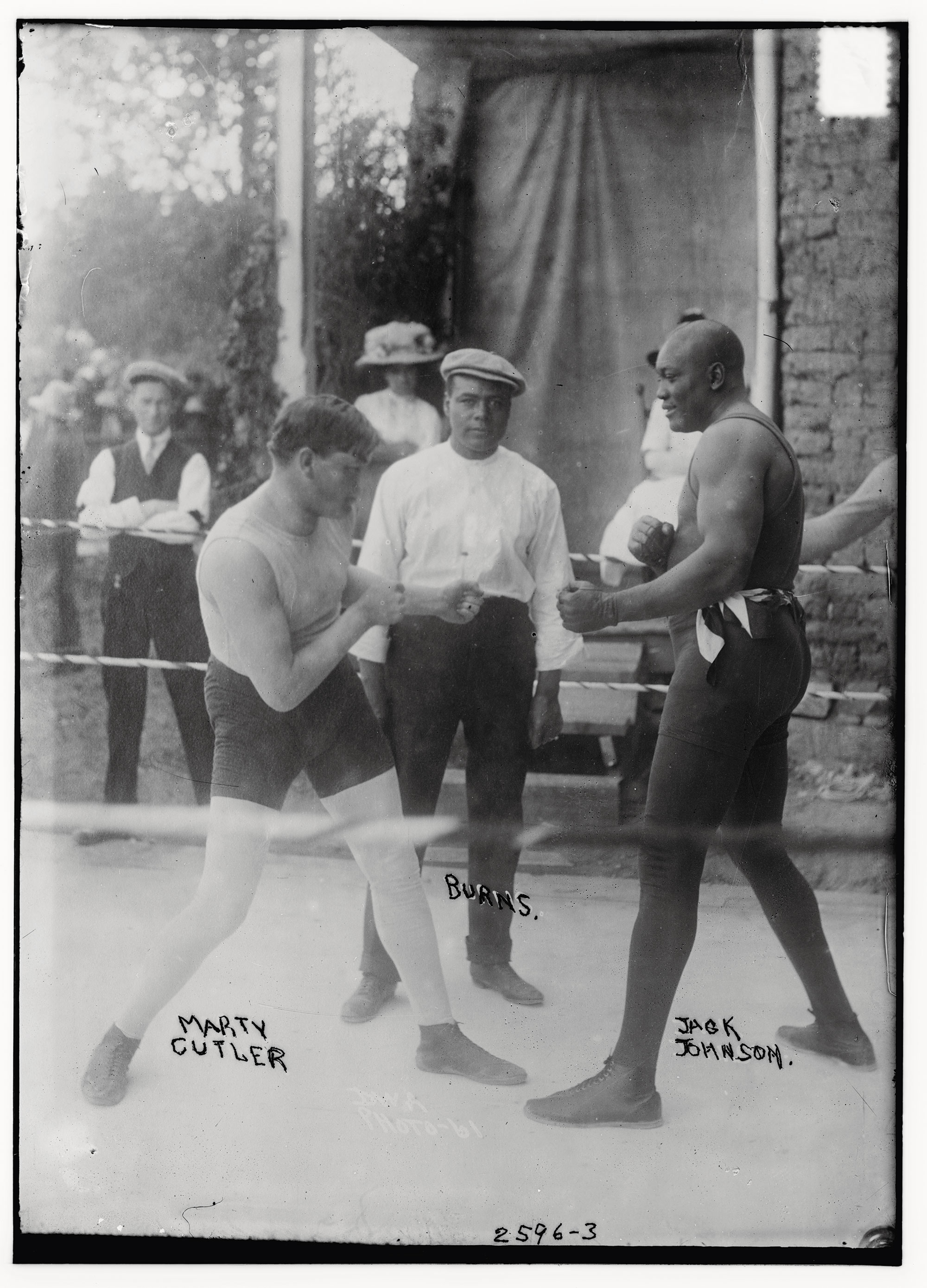

After winning the world title in 1908 with his 14th-round knockout, in Sydney, Australia, of Canadian boxer Tommy Burns, Johnson held onto his belt until 1915. As a fugitive in Havana, Cuba, he lost to Jess Willard, a white American. He boxed more after getting out of jail, adding to a lifetime total of more than 100 bouts, but mostly lived off his celebrity. In 1946, at 68, he died in a car crash in North Carolina and was buried in a family plot in Chicago.

Collins has grand plans for how Galveston can celebrate Johnson to enhance tourism. He dreams of a 60-foot statue—like the one of Sam Houston on Interstate 45 in Huntsville—of Johnson standing atop the Daily News building at the end of the causeway. Recalling Black Panther again, Collins adapts the film’s signature Wakandan salute: “Galveston forever. Jack Johnson forever.”

Jack Johnson’s Galveston

The memory of the Galveston Giant lives on at these island locations.

A bronze sculpture by Adrienne Isom at Jack Johnson Park at Old Central Cultural Center

2601 Ave. M.

A painting of Johnson on the wall of the African American Museum

3247 Sealy St.

Jack Johnson Boulevard, formerly 41st Street, runs from Galveston Harbor to the Seawall.A Jack Johnson tree sculpture inside The Oaks subdivision, accessed at 45th & Broadway.

A painting of the boxer at The Bryan Museum

1315 21st St.