All You Got Left

A family’s indelible memories of Lubbock’s Joyland Amusement Park

by LaToya Watkins

It was also the last day I felt the city of Lubbock was my home.

Daddy died two days after that photo was taken—two days after cotton candy, soft serve ice cream, grab bags, chili dogs, and roller coasters. My mama packed us up, and we moved from Lubbock to Dallas almost immediately. She had his body sent to Dallas because he was from there. He’d followed Mama to Lubbock like a lost pet, or maybe like something feral, after they were married in 1982. He joined her in the place that billed itself as “The Friendliest City in America.”

I reckon it was a friendly place to people who didn’t look like us. For Black residents, Lubbock was different. The city, founded in 1890, had only one Black neighborhood up until the 1970s, when a destructive tornado swept through the city. In the aftermath, segregation laws and practices abated enough to allow some middle-class Black and Hispanic families to move to other parts of town. This new Black neighborhood, the East Side, had been designated by city officials as the city’s main industrial area, where residents were exposed to environmental pollution and hazards. Government subsidized housing was concentrated in poorly maintained East Lubbock. To this day, gas stations, restaurants, and other businesses are scarce on this side of town. Nonetheless, Daddy followed Mama to this place, where she grew up and had family, and stayed until he died.

In my young mind, Daddy was still at Joyland at the picnic table. When we returned to Lubbock from Dallas for funerals or to visit my mother’s family, I hoped we’d have a reason to head west on Parkway Drive. We’d pass Joyland, and there’d be just enough daylight for me to get a glimpse of Daddy on the Skyride. Maybe he’d wave at me, mouth I love you, and that would be enough to fill the void.

Last year, I started a journal about “home” for my first grandchild. It made me chuckle that I thought of Joyland, and how it felt natural yet strange to remember the Scrambler, the Rock-It-Express, the bumper cars, and the Whip. Now, a year after I started the journal, home is more difficult to define. I don’t think I’ve felt at home in one single place in a long while. But I want to gift him something that wasn’t gifted to me. I don’t want to give him the oft-cited cliches I’ve heard people say: Home is where your people are or where your heart is or what matters to you most. I’m not saying those things aren’t true, but I want to leave him with something more personal than that. I’ve spent much of my adult life attempting to piece together what the first Americans tore apart for so many of us: home. I don’t want that for my children’s children. I want to leave them with answers they can hold in their hands. It makes sense to start with Joyland.

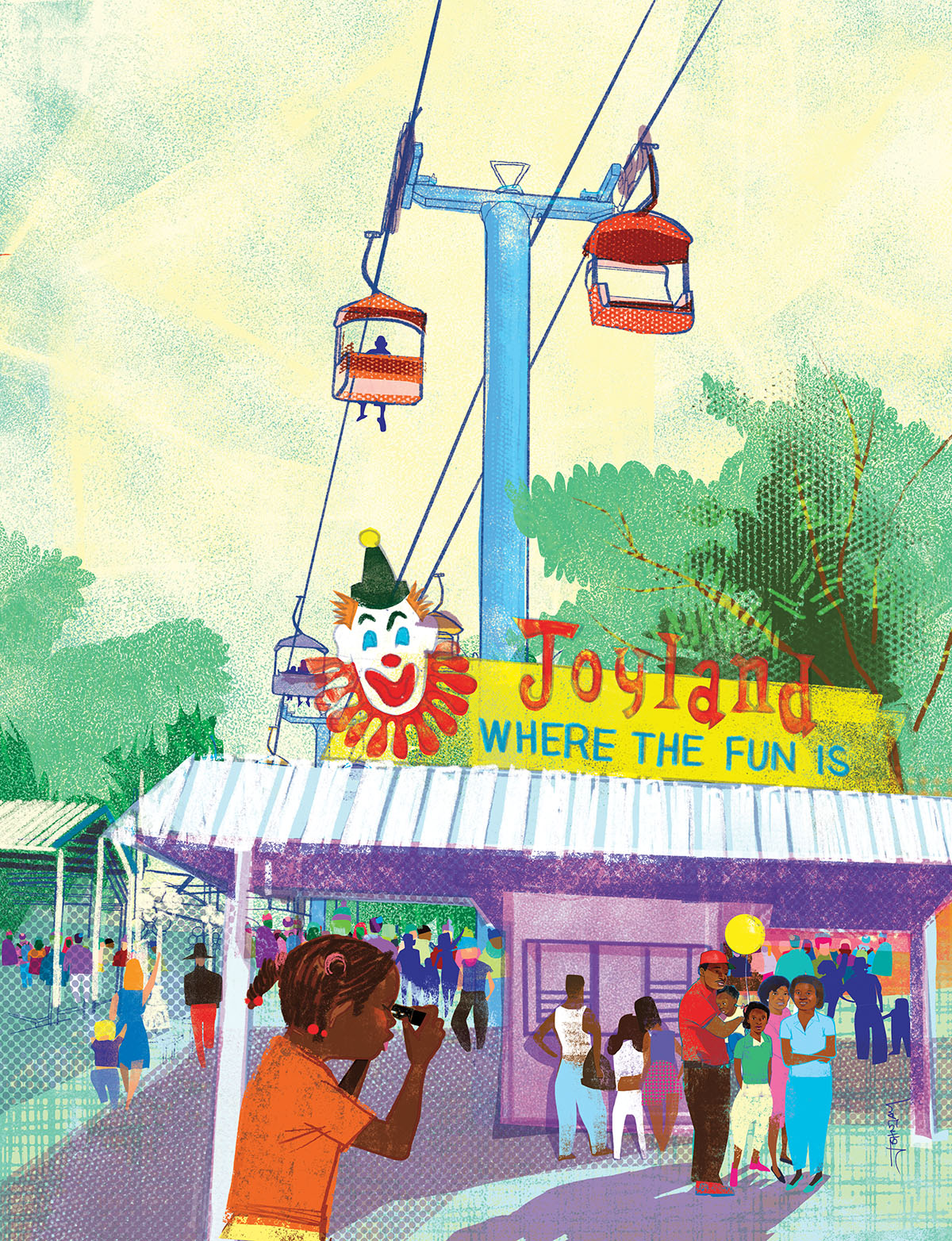

Joyland opened in the late 1940s as Mackenzie Park Playground. It was later known as Whit’s Playground before taking its final name of Joyland Amusement Park. It was a popular attraction in the West Texas area in the early days, but as zoning and racism began to shape the growth of the city, the park was left dilapidated. Joyland went through multiple owners before the Dean family bought and started revitalizing it in 1973. Early city leaders couldn’t have anticipated the level of displacement the tornado of 1970 would lead to for so many Black and Hispanic residents. It drove them into the most eastern white neighborhoods, such as Parkway. Black and Hispanic families moved in while white families moved out. Joyland bridged the gap in these divides, becoming a source of fun for all the people of Lubbock.

I visit the park’s website on a Sunday afternoon in January and learn that it’s permanently closed. After 50 years of thrills, Joyland is gone. I think about how much the park meant to the Black community when I was a girl. How seeing the giant rides spring up through the trees from Parkway Drive reminded us we were as real as the rest of the city that was modernized without us. How it was the last good thing we had. The park’s website lists contact information for inquiring about buying old Joyland attractions, so I send a message and pray the Skyride hasn’t been sold.

By the time I sit down for dinner that evening, Kristi Dean has replied to my email. She’s passed on her husband’s contact and says he’d be delighted to discuss Joyland with me. Suddenly, everything is black and white. I don’t know why it scares me, this idea of speaking with them. I fear our conversation will be about race, and I don’t want to have it.

It takes me three days to decide to get in the car and make the drive to Lubbock from Dallas. I think about taking what my mother and uncles used to call the “back way”—US 380 to State Highway 114 to US 84—but I’d never hear the end of it from Mama if she called me and I didn’t pick up. Cell service is sketchy on SH 114, and there’s not much to see. Mama once said, Highway’s dangerous for a Black woman to travel alone, but that one’s the worst. And I know she’s right. There’s an open family secret that one of my great aunts was attacked and left for dead on that road in the ’80s. We rarely take that route to Lubbock now that all my uncles, the ones who kept us safe, are gone. The back way would save me an hour, but it’s hardly worth the risk. Besides, most of my memories wait for me on Interstate 20; it’s something like grace stretching itself out for me.

I haven’t been on the road long when I take the exit in Cisco and pull up to one of the gas pumps at Allsup’s. I haven’t used much gas, but this stop is about more than that. I go inside the store and say hello to the woman at the register, head to the back and grab a drink, then come back and ask her if they’ve got burritos. “I just put some out fresh, sugar,” she says. She rings me up and makes small talk. Asks me where I’m from. When I finally look up at her, I see a genuine, imperfect smile, and something in me relaxes.

When I leave the store, I walk to the left side of the building instead of returning to my car. The sight of the parking spaces on this side, all empty, brings me back to a gloomy day 10 years ago when my sisters and I occupied those spaces. We were headed to meet Mama in Lubbock. To catch her body because her mama was dying. We were sitting here, waiting for our children to empty their bladders and buy their burritos, when Mama called and told us Grandma was gone. Cars were pulling in and out of the spaces that Sunday afternoon. Life went on as usual in the little town. After the call, we sat quietly in our cars, thinking about the relationships we had and didn’t have with our grandmother. We thought about the time we’d assumed we’d have, and we worried about who’d catch Mama if she passed out from grief. This is where I was when my grandmother was last alive, and this is where I was when she died.

Down the road, I exit in Abilene. There’s a Chick-fil-A here, and I could use a lemonade. That’s not why I take the exit, though. The first time I drove this familiar detour I was so nervous I was sweating. This time is different. My hands don’t sweat when I hit Farm-to-Market Road 3522, where the land is so flat I can see everything without strain. When I drive by the French Robertson Unit and peer out at the rows and rows of crops, I’m calm. I’m not worried about guards making me open my trunk before I park or patting me down like the last time I drove to the facility.

On that visit, my cousin was happy for a visitor so soon after hearing of Uncle Gerald’s death. His once-white prison suit was over-starched, and he walked stiffly, like the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man from Ghostbusters, when the guard escorted him out to me. He sat down and lined up all the snacks I’d bought from the vending machine in front of him. He smiled at them like he was a pirate and they were his treasure. He opened them slowly and savored each one. It made me sad because it had been 20 years, and he had never been a man out in the world. We talked about his release—it was close. He promised he would do so many good things. He’d get life right with this second chance. I hoped and believed he could. He was released the next year and headed straight to East Lubbock, and we all held our breaths. He hasn’t gotten around to doing those good things we hoped for him that day, but when I’m in Abilene, I always take that exit from I-20. That stretch of highway makes me feel close to him; that’s where my hope in his future lives; that’s where he’ll still do so many good things.

At some point, a wave of nostalgia surprises me. I call Mama and ask her about Sweetwater—if that’s where I make the split to US 84. Sweetwater, she says. You halfway. No turning back now. I remember my father’s voice and maybe him saying the same thing some 37 years ago. I ask Mama about it. About Freddie Jackson in the tape deck of our old Buick Riviera. She’s silent for a moment and then she tells me I’ve always been good at holding the past in my head. She tells me we’d taken a trip to Dallas—visited his family before he died. We made a plan to move back, she says. Gave ourselves six months. We didn’t know we didn’t even have one. After she says that, I ride in silence with Mama on the Bluetooth, the dirt hills getting redder with each passing mile. Mama finally sighs and says, I can’t believe you remember what was playing. I couldn’t listen to “You Are My Lady” or none of the songs on that record for years after y’all daddy died. She tells me it was his favorite and all she could do to forget about him was to forget about all he favored. I take Mama off Bluetooth and put her on speaker, and then I tell Siri to find the album. When “You Are My Lady” comes through the speakers, I smile and hope she’s smiling too. If she’s doing what I’m doing, she’s running her mind back, trying to hear him on this very stretch of road, trying to remember all his favorites, trying never to forget again.

I notice the wind turbines when I split from I-20 to US 84 in Roscoe. It makes me sad to see them spinning so perfectly. I first saw them in 2008 when we traveled to bury Uncle Junior, one of the uncles who helped raise me after my father’s death. He never saw the majesty of the turbines; he died before they were erected.

When I was a girl, there were oil pumps in my next stop in Post. That’s where we stopped for burgers. My people think nothing beats Holly’s Drive-In. Toasty toasty, greasy greasy. That’s how we order them, and it isn’t done right if it doesn’t drip in your lap. When I pull up to the old stand, I smile at the sight of the red-and-white awning. The last time I came through here, in 2021, it was dusk. The red and white didn’t look half as bright. I was with Nene when we heard a loud, familiar woman entering the building. I asked Nene if the woman was one of our great-aunts. She shook her head and said, No, that woman has no teeth. Aunt P—’s got teeth. We found out the next day, at my favorite and last uncle’s funeral, that it was indeed our great-aunt. She laughed and kissed our cheeks. Y’all better know your people when you see them, she said.

I begin to smell livestock just past Slaton and sit up straight because I’m close. I remember visiting Pinkie’s Liquor on the outskirts of Lubbock when I was young. Our two- or three-car caravans never passed by without stopping for baskets of chicken gizzards, brisket sandwiches, burritos, packed snacks, beer, and gas. Gizzards were my favorite. I liked them exactly how Uncle Rickie liked his. The paper basket, stuffed inside a white paper sack, dripping in grease and smothered in house-made hot sauce. In my memory, Pinkie’s is a large gas station with the biggest food bar I’ve ever seen. For the people of Lubbock—for my family—it was more than just a filling station. It was a hub for coming and going but also something like therapy. See, Lubbock was one of the largest dry cities in the country until 1972, when voters gave restaurants and bars permission to sell alcohol. But they confined liquor stores to a single Vegas-like stretch at the edge of town. It was known as the Strip to folks in the western parts of Lubbock and the Line to folks in the most eastern part.

As a young girl, I knew it as the place you got liquor and some of the best barbecue and jerky. Those big marquee signs were a real sight at night.

I can’t stop at Pinkie’s this time. It no longer sits out past the Lubbock County line. The Line is altogether a thing of the past because Lubbock is no longer dry. The shell of Pinkie’s still sits there, though, like something burned and gutted. I pull over when I approach it, get out, and lean my body against the car. I relax my shoulders, fold my arms, close my eyes, and allow the memories to come back to me. I stand here in this hallowed space and watch my uncles pump gas, laugh with their sister, and run in and out of the well-lit store. They carry beer and whiskey and all the good things we’ll need to welcome ourselves home. They check on us and protect us and promise us, Just a few more miles, y’all. Just a little while longer.

I open my eyes, pick up my phone, open the email from Kristi, and dial the number she’s left for her husband. David Dean answers on the third ring, and I stutter through my reason for calling. I don’t know why I’m surprised by his kindness, by his love for all things Lubbock, for West Texas, for Joyland and the work his family has done. It’s a pleasant conversation, like chatting with an old friend. “I can talk about Joyland all day, LaToya,” he tells me near the end of our call. “It’s always been about the smiles, the fun, the memories, and the generations for us. Sometimes, the memories are all you got left.”

He’s choked up for most of the conversation, so I don’t ask him about the Skyride or any of the other rides at Joyland. He’s been fighting to save this place for a long time. It’s only now

setting in that he’s lost this battle, and it dawns on me that he’s likely in a stage of grief. Months later, he would die.

I stand in front of Pinkie’s awhile and think of all the people I’ve lost and all the places I visit to hold on to them. I wonder what it means that one day it will all pass away. I feel a sad smile stretch across my face as David’s words return to me. Sometimes, the memories are all you got left.

I don’t know what I’ll write to my grandson. Perhaps I’ll never know the meaning of home, but maybe home is the places I’ve collected from the people I’ve collected. Places I visit because they still exist and that’s what keeps my people alive. Or maybe home is grief and love and disappointment and change. I’m not sure yet and don’t know if I’ll ever be.

I don’t think it matters much what I write in the journal because I’ve learned that home is something I can’t gift him. I can give him a house, but he’ll spend his life in search of his own home. He must come to it on his own in the way I’ve had to, in the way I still do. I’ll write what I know when I figure it out—if I figure it out—and leave him as much as I can to guide him.

But for now, I can’t risk seeing the Skyride gone today or tomorrow or anytime soon. That’s a home I’d like to keep intact for myself. I want my father to always be in the seat of the Skyride waving at me, mouthing I love you. I want to hold Joyland and Lubbock and Daddy in my heart that way. I climb into my car, put on some Freddie Jackson, and head back the way I came.