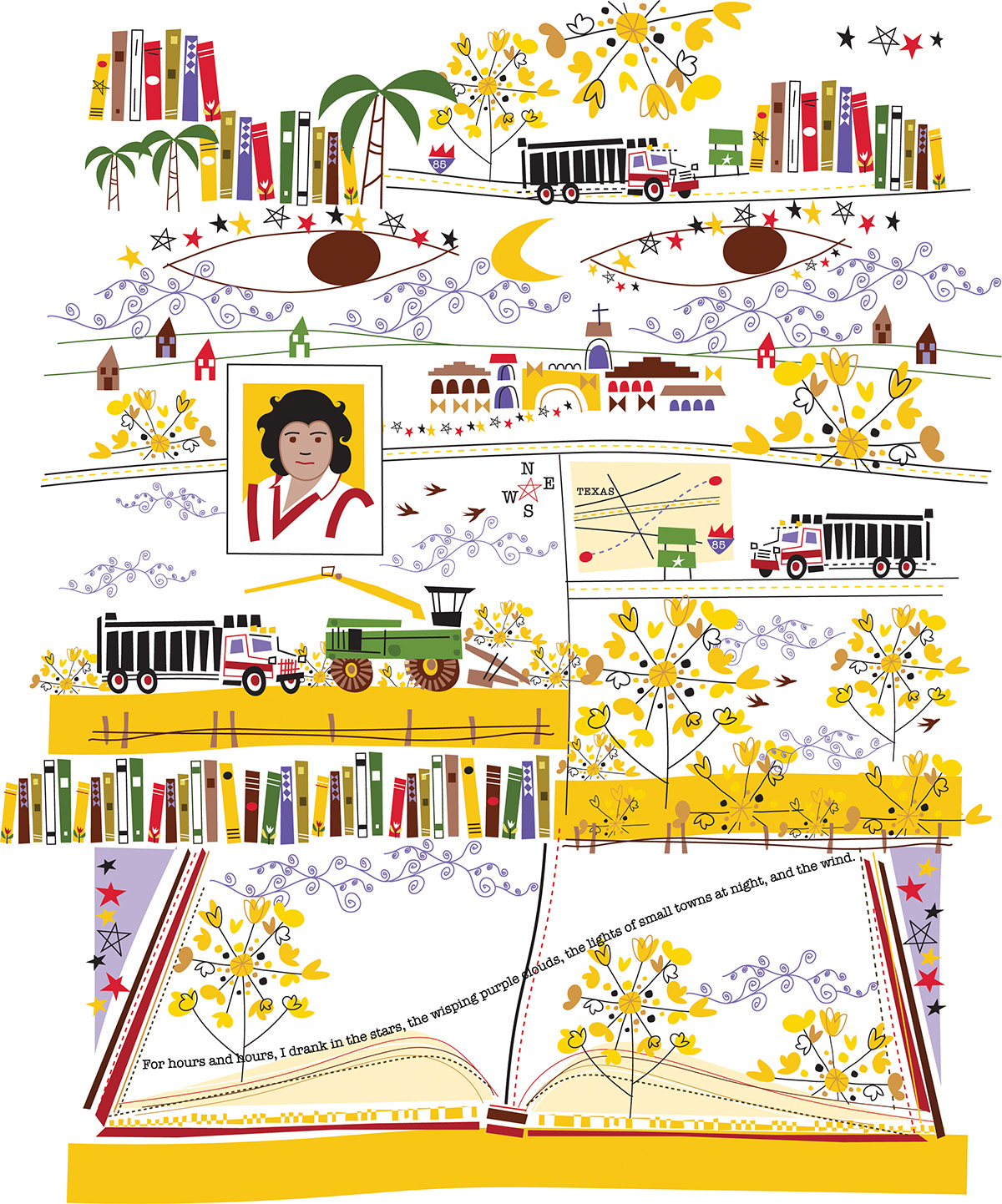

A Place Before Words

What a childhood on the road taught a daughter of migrant truck drivers

by ire’ne lara silva

A National Magazine Award finalist

I learned how to read a map before I ever learned how to read a book. In one of my first memories, I am 4 or 5, kneeling on a chair, trying to see without getting in anyone’s way. The Rand McNally map is spread over the dining room table. My father is standing with a thin black marker in his hand as his booming voice explains the route we’ll be taking. With infinite care, he traces the spidery red lines and thicker blue lines on the map from our home in the Rio Grande Valley town of Edinburg to the Panhandle. There is no background noise, no TV or radio noise, no fidgeting on my part or my siblings’. This is done with the seriousness and care of ritual. There can be no mistakes, and there is no time to waste. The contractor called—he’s ready to start harvesting, and my father’s trucks are expected in the fields, ready to work, in 36 hours.

This is 1979 or 1980. My parents are truck drivers who cyclically follow the harvest seasons of various fruits, vegetables, and grains throughout Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. My parents don’t drive the 18-wheelers most people associate with truck driving. Instead, they drive box trucks with only 10 wheels and truck beds that are modified according to the needs of each crop. My parents, born in different parts of South Texas in the late 1930s, attended only the first couple years of elementary school. They were predominantly Spanish speakers but with so little formal education, they were unable to read or write in either English or Spanish. Because of this, when my father read a map and laid out the route, he spoke in a language of numbers and directions.

We always set out in a convoy—at first three trucks, later almost always four. My father, my mother, one of my siblings, and sometimes a hired driver, or chofer. The choferes became common after my older siblings left home. They came looking for work, and over time some of them became family friends. Once the farmer and the contractor had decided it was time to start harvesting, the contractor would call the truck drivers and we would set out. For the weeks or months that we lived in different towns, we resided in everything from labor barracks to rented motel rooms, apartments, or houses. From September to May each year, my siblings and I would enroll in at least three different schools. My parents worked long hours, sometimes from 6 a.m. till nightfall, hauling crops from the fields to the local processing plants.

My “good English” led to my calling potential landlords to see if their apartments or houses were available for rent. Vacancies sometimes vanished spontaneously when my Indigenous-Texan-Mexican-American family showed up in person.

On the long cross-state treks, I usually traveled with my mother. But once, when I was 8 or 9, I traveled with my father. I read out every sign, creek name, highway direction, and town name for the 850 miles it took us to get where we were going. In hindsight, I’m not sure how this wasn’t incredibly annoying—and my father was an easy man to anger. But instead, he listened, tilting his head when it was an unfamiliar name and sometimes repeating it to himself. So many times, he said, “Oh, that’s what it’s called” (in Spanish), and then proceeded to tell me a story about the creek where snakes had frightened him and his childhood friends, the spot on the highway where a tire had blown out at night, the town with the best barbecue sandwiches ever, and so on.

My mother couldn’t help me with my alphabet or read me children’s books, but she taught me so many other things. The orientation of the sun. The direction of the wind. Signs of rain. How to instantly tell north from south and east from west. She drove with a relentless concentration and care, never speeding, never falling below the speed limit, hyperconscious of other drivers on the road. I didn’t know it then, but these were lessons for the writer I would become. I started writing at age 8 and never stopped. On the page, I was never lost. On the page, I was all concentration and care.

Since 1998, I’ve made Austin my home. In the last decade, I’ve published three books of poetry and one short story collection. Somehow, with a 40-hour, Monday-to-Friday clerical government job and responsibilities as a caregiver for my disabled brother, I managed to make 60 events in 2019 throughout Texas and as far away as San Francisco and Maine. I taught workshops, met with students, and read my poems and stories at universities, book festivals, and community centers. I drove an incalculable number of miles within Texas last year, during which memories of old trips vied with new impressions.

There were two trips to South Texas that opened my eyes anew. There, I visited students at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, read in front of the border wall at the foot of a 900-year-old Montezuma cypress tree, attended the Texas Institute of Letters’ annual banquet, and shared a stage with Latinx writers at the McAllen Public Library. I’d very much wanted to read at that library, not just because it’s the largest single-floor library in the United States, but because I knew the patch of land it was built on.

When I was a child, it was a wide, wide field where they grew mustard plants. It bloomed golden all the way to Nolana Avenue, and after that you could see palm trees and all the dramatic colors of the sky. When they covered those golden fields with concrete and asphalt to build a Walmart, shops, and restaurants—and later the library—that view disappeared. Decades later, the first photos of the library I saw showed parts of the interior painted the same yellow as those blooming mustard plants.

My parents didn’t know what to do with me. I didn’t go anywhere without a book. I kept books under my pillow, under my mattress. I kept them in the bathroom under the sink so I could sneak in a few pages. I read until I had to turn off the lights, and then I read by flashlight or streetlight or any light that let me distinguish one letter from another. I took books with me when we traveled from place to place. Early on, I remember devouring Laura Ingalls Wilder and L.M. Montgomery and Louisa May Alcott; everything I could get my hands on about King Arthur; and the novels of Lloyd Alexander. Every cent of my allowance went to books or writing supplies.

My voracious reading made me the official reader and translator of all family mail. By the third grade, I was registering myself and my younger brothers into multiple schools. My “good English” led to my calling potential landlords to see if their apartments or houses were available for rent. Vacancies sometimes vanished spontaneously when my Indigenous-Texan-Mexican-American family showed up in person.

She might have been unread and unlettered, but my mother knew the importance of education. When my father threatened to pull my older sisters out of school so they could work as drivers or in the fields, my mother said she would drive one of the trucks. My oldest sister is 17 years older than me, so I never knew my mother when she wasn’t a truck driver. I think my mother was prouder of my siblings’ high school diplomas than they were. Without complaint, she drove for more than 30 years, until only a few months before her death in 2001.

When I came home from my first year at Cornell University, aflame with everything I’d learned about Texas history and Chicano studies, she was the one who told me more about Gregorio Cortez, César Chávez, and La Raza Unida (formed in Crystal City, where she was born and raised). She also told me about LULAC and Henry B. González organizing for education, and she explained that truancy laws in Texas had not been enforced when it came to Indigenous-Texan-Mexican-American children when she was a child. The farmers and local economies were reliant on cheap labor and wanted all those brown bodies working in the fields.

Neither of my parents lived to see me publish my first book in 2010. I sometimes wonder what they would make of my life as a writer. Most of my travel now is solitary and independent. As far as I can remember, my mother never went anywhere unaccompanied by her husband or one of her children. In her life, she never boarded a plane. She would say stages and screens privileged the thin, the beautiful, and the light-complected. What would she make of me now? I am none of those things, but I know I’m meant to take up stages and speak to groups both large and small.

I write the truest things I know. Sometimes I write about mortality and grief, the body and illness, violence and history, sexuality and desire, transformation and hope. And then I go in front of audiences and share all of those thoughts, emotions, and experiences. I wonder what my father, who lived eternally with the shame of what other people thought, would think. I wonder what my father and mother would both think of the permission I give myself to say or do the things I do every day as a writer. They lived lives circumscribed by their socioeconomic status, their race and ethnicity, their lack of education. Even on those long cross-state treks as kids, my siblings and I wore our school clothes and kept them clean. If we were turned away from restaurants, motels, or other places, it was not because we were dirty, my father would say. And we were turned away many times.

What is rewritten, what is soothed, what is redressed by me being invited where I never thought I’d be welcomed? To address students of diverse backgrounds educating themselves about literature, history, and art? To tell the stories of my imagining and my lived experience in all these places? To take a stage, to take my time, to listen, to speak, to share, to discuss, to teach?

In some ways, traveling as a writer reminds me of my parents’ seasonal travels. I go where I am called. And often, I’m called to the same communities, the same universities —because my work is taught to students year after year, and because I believe art is a relationship you build with others. I take to the road to do my work, to follow where my words have gone before me. All of these roads are mine, as familiar to me as my mother’s face. Perhaps another woman would be afraid to travel alone. Not all parts of Texas inspire confidence in people with brown skin, Indigenous features, or LGBTQ identities. But how to describe what it means to be invited? To be welcomed? Even as my size or color or what I say may take some aback? How to describe what it means to claim roads and claim spaces and to share my work?

I wonder what my father, who lived eternally with the shame of what other people thought, would think. I wonder what my father and mother would both think of the permission I give myself to say or do the things I do every day as a writer.

Everywhere, I find students and readers eager to listen, eager to ask me questions, eager to share their stories with me. Everywhere I go, I find bridges with lovers of language, students of history, activists, cultural workers, readers who have never read stories about the places they come from, students who have told me that my presence and my work make them brave enough to write their own words. This, in turn, makes me braver and more truthful—on the page and in the world. It makes me willing to take on full-body pat-downs at airports, communication difficulties with those who don’t believe I’m a writer or a U.S. citizen, or withstand those hours at night on the road hoping my vehicle doesn’t break down.

While the bulk of events I’ve done has been in Texas’ largest cities, I’ve also had the good fortune to visit rural spaces. I’ve done this through the Writers’ League of Texas’ Texas Writes programs, which offer free presentations and discussions with published writers, and through the Texas Commission on the Arts’ rural touring grants. In 2017, I was awarded a rural touring grant to visit the area around Laredo. I visited high schools, community colleges, and libraries in Leakey, Uvalde, Carrizo Springs, and Crystal City.

To get to Leakey, I passed by all the wonder that is Garner State Park. My parents used to haul peanuts in Uvalde before I was born, but I didn’t go visit the crops this time. Instead, I spent a lovely afternoon at El Progreso Memorial Library in Uvalde, with its abundant wildflower garden. Carrizo Springs was charming and welcoming with its miles and miles of thorny mesquites. I’d planned to spend more time in Crystal City—I’d wanted to see if I could find my great-grandparents’ graves or even just to sit and think of my mother as a child there—but the visit to Southwest Texas Junior College took up the whole day. I logged almost 1,600 miles on those four trips from Austin to those small towns, and I was grateful for every mile of road, every bit of wonder I felt.

I’ve seen many beautiful things in my life, but the memory of that trip still fills me with wonder. That is what writing at its best feels like to me—movement without time, drinking in starlight, alone and not alone.

Writing is wonder in the same way travel is wonder. One winter when I was 12 or 13, I traveled with my mother and two of my siblings overnight from Hereford to Edinburg. I don’t remember why it was urgent, but I remember we only stopped long enough to get more gas and to pick up food and coffee at a Whataburger. We were in my father’s pickup truck, and there wasn’t enough seating for all of us. I volunteered to make the trip in the pickup bed by myself. There was just enough room for me to make a little cot out of a couple blankets.

It was dusk when we set out. I watched the night come, watched the stars emerge the way they do in the rural parts of Texas, where there are sometimes hardly any trees, where you can sometimes see horizon to horizon. The sky is so immense it feels as if the earth will give way. I didn’t sleep at all that night. For hours and hours, I drank in the stars, the wisping purple clouds, the lights of small towns at night, and the wind. More than 700 miles of night sky and road. I’ve seen many beautiful things in my life, but the memory of that trip still fills me with wonder. That is what writing at its best feels like to me—movement without time, drinking in starlight, alone and not alone.

Before the pandemic struck, I traveled to Corpus Christi at the invitation of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi to read and lead a writing workshop for a group of 150 area high school students. The size of the group was a bit of a last-minute surprise for me, but it’ll remain one of my favorite memories because of the students’ enthusiasm and tenderhearted honesty. I felt at home in Corpus Christi. It brought to mind memories of hot summers when my parents hauled sorghum in nearby Mathis, Edroy, Robstown, and other little towns that were hardly more than city limits signs and Dairy Queens. Where my parents harvested crops, I sow the seeds of ideas.

Where do we start the story of the road and of writing? We start in a place before words. A place filled only with the rushing of the wind. I remember my mother’s profile, dark and Indigenous, her small, strong hands on the steering wheel. I remember the beginning pink of dawn. I remember my 5-year-old hand reaching out the window, the wind on my face, my curls waving wildly. How I felt like a bird, both small and powerful.

I had no idea all my planned travel for 2020 would be wiped out so mercilessly this past March. But I know other days and other trips will come. The road lives in me. The road has made me the writer I am. I am the child of highways, of Texas skies, of hardworking people who harvested the land. I am the child of manual labor and skilled hands. I am the child and creator of border stories and folklore, the storyteller shaped and haunted and beguiled by this land. I learned language and its rhythms on these highways—endlessly rolling, sometimes slowing, sometimes labored, sometimes effortless. This is where I learned to breathe and to shape words and to become all of who I am. I can’t resist who I am. This is what the road taught me. This is what the road still teaches me.