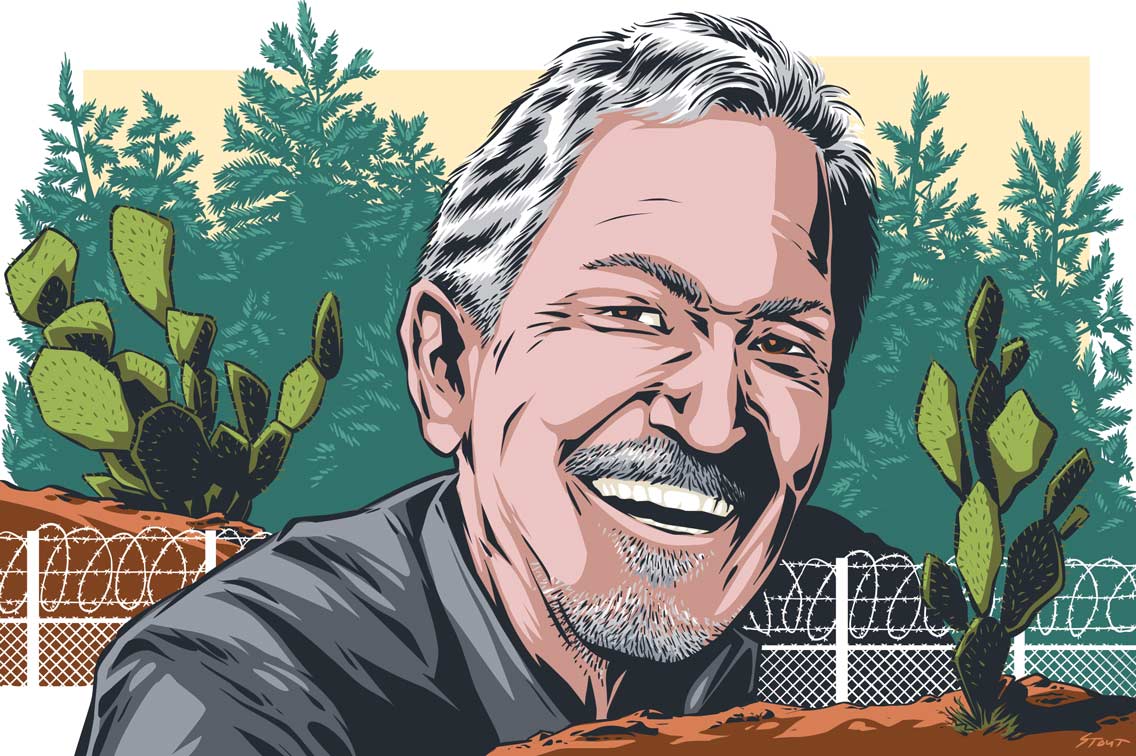

Illustration by Jason Stout

Don’t be surprised if you fall in love with the characters in Benjamin Alire Sáenz’s fiction. Be it with two high school friends taking on the world in his celebrated young-adult novels, or with people stumbling through loss in his short stories, or with the shining voice of his poetry, the El Paso-based writer expands your perspective and opens your heart.

Since the global success of Sáenz’s 2012 book Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe—a tale of two teenage boys in El Paso sorting through questions of identity, family, and love—he has become a star in the world of young adult fiction. At literary engagements from Seattle to San Antonio to Bogotá, the 63-year-old is called on to discuss topics like writing, coming of age, and sexuality. He’s now at work on the sequel to Aristotle and Dante as well as a screenplay for a movie version, scheduled to be filmed in 2019.

El Paso and its neighboring border city Ciudad Juárez are in Sáenz’s blood. The arid landscape and its people live inside him and fuel his stories. Sáenz helped found the University of Texas at El Paso’s bilingual MFA creative writing program, the only one in the nation, and taught there until his recent retirement. In 2013, he won a PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction for Everything Begins and Ends at the Kentucky Club, a collection of short stories that follows characters through heart-rending loss and redemption, all weaving in and out of the famous Kentucky Club bar in Juárez.

Sáenz’s apartment on the edge of downtown El Paso is a light-filled paean to art and life on the border, every inch covered in his vibrant paintings, poetry, and books. As he kicks back on the couch to talk, fresh ideas and moments of epiphany bubble to the surface like a river that can’t help but flow.

Q: So many of your main characters, especially in Everything Begins and Ends at the Kentucky Club, are grappling with loss. But they keep moving forward. What keeps them afloat?

A: Well, they want to live. Something inside of them knows that life is a gift, and even if they don’t like themselves enough, or very much, they still know that a gift has been given to them. And they just want to live. They’re like me. And they don’t want to be cheated out of that.

Could you tell me about your recently released poetry collection, The Last Cigarette on Earth?

I threw so many poems out and wrote some new ones, and it evolved. I had to distill it into the poems that I thought mattered most. You know, it’s too long as it is, but the poems that I felt were essential to the journey that I was talking about stayed, because it’s also about Juárez. It’s about me, Juárez, love. I’d never been in love with a man until I was 55. I thought it was incredible. I also thought it was a disaster. It wasn’t anything I’d ever known, and I somehow felt compelled to write something about it, and that’s what this is.

How does it feel to write about such intimate subjects?

You know, I don’t have a car anymore. I was in a terrible accident about three months ago in which I almost died. It’s changed me in some good ways. Not that I took life for granted, but now I think, “I’m alive and I’m going to make it count.” I was at a writing conference and this woman said, “I’m afraid of alienating people with my work.” And I said, “Oh, hell no. I want to make friends, I do, but I also want to earn my enemies. If they don’t like me for what I write, then I want them for enemies.” I’m sorry, but if everybody loves you, then Houston, we have a problem.

I’ve heard from many locals that El Paso and Juárez are one big community. What’s your take on that?

You cannot imagine one without the other. There is no El Paso without Juárez. There is no Juárez without El Paso. We want to be our own thing—and we are our own thing—but we’re not. If Juárez shrivels up and dies, so do we; and the other way around. We need each other for survival. Because most people don’t even know us. I wish people understood that the people of the border love their country, except for their country is two countries. We’re a cultural ecotone.

What do you mean?

In nature, an ecotone is where one geographic reality is turning into another. For example, in the high deserts of New Mexico, you have elements of the desert and elements of the forest, so a cactus is growing next to a ponderosa pine. It’s not the desert anymore, and it’s not the mountains yet, but it has elements of both.

Would you ever live anywhere else?

This town, this city, this border, Juárez—it is my great passion. I’m not going to let anyone break that love affair up. If you don’t get that about me, you don’t get me. Some people paint those of us who live on the border as being poor, lazy, shifty, uneducated. We are not lazy, that’s for sure. We are very innovative, we have a great sense of humor, we don’t hold grudges, we take what is there and we make something out of it. But we are always going to be outliers to the rest of the world. In one review of a book of mine, they liked the book and they wrote, “Despite the fact that the characters are Hispanic, and that the setting is El Paso-Juárez, the story is universal.” Despite the fact. That means that, generally speaking, this reviewer doesn’t think the story can be universal if the characters are Hispanic and if it’s set in a particular place. Now, if it’s set in New York or Paris, it can be universal. But, if it’s set on the border, you have to mention that despite that, it’s still universal. So many people don’t know anything about us, but they have decided who we are.

Do you think the drug violence and instability in Juárez is getting better?

It really is. I have a lot of friends who work there and are teachers there. They are incredible people. They’re always so grateful when I go over and read to their kids. I just go over for a day, but those teachers are there every day. If we only had any idea of the sacrifices people make to educate their children in Juárez, maybe we’d rethink our assumptions. That’s why I’m staying here. I’m going to change someone’s mind, even if it’s just one person.

What is one thing you love to do in El Paso?

On Sundays I walk to the border, to the bridge and back. I walk through Segundo Barrio. I stop off at The National, it’s a great bakery, and talk to people I know. They have the best bolillos, so good. It’s white bread that’s crusty and soft inside. They also have these pastries called libros. It’s a square that’s really flaky, and the layers are like the pages of a book.

How does success feel?

I’m a working-class guy. I know how to work, and I like working. I’m not afraid of being poor again. To have once had nothing, to know that you did this on your own, that’s amazing, and no one can take it away from you.