Tonkawa Tribe members photographed in 1898. Photo courtesy Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma

Tonkawa Creek spills over time-worn rocky bluffs and splashes into a clear blue-green pool at Tonkawa Falls City Park in Crawford, a half-hour west of Waco. Workers employed by the Depression-era Texas Civil Works Administration, the precursor of the Work Projects Administration, gathered stone along the creek to build steps leading down to the water. Today, a concrete bridge stretches over the falls, offering a bird’s-eye view of the tranquil setting below.

The creek and park were named for the Tonkawa, nomadic hunters and gatherers who lived in Texas for millennia but were forced out of the state by the federal government. The Tonkawa name also appears around the Austin suburbs of Georgetown and Round Rock on street signs, housing developments, and RV parks, as well as Tonkawa Bluff, a site along the San Gabriel River where tribal hunters drove bison off the cliffs.

Except for place names and a bronze bust of Tonkawa Chief Plácido along the banks of the San Marcos River in San Marcos, there’s not much else to commemorate the people whose ancestors inhabited the spring-fed oases along the Balcones Escarpment going back 16,000 years. But local advocates in Round Rock are pushing for acknowledgement of and education about the tribe.

Every local history of Round Rock “begins with at least some mention of the Tonkawa as the original inhabitants of this area,” says Blane Conklin, a former commissioner on Round Rock’s Historic Preservation Commission. Along with fifth-generation Round Rock native Tina Steiner and sculptor Antonio Muñoz, Conklin nominated the Tonkawa for the city’s 2019 “Local Legends Award” to recognize the tribe’s significance. The annual award presented by the Round Rock Historic Preservation Commission honors people who had a “positive and lasting impact on the culture, development, and history of Round Rock.”

Muñoz says that while the histories and legends of the Comanche, Lipan Apache, and other tribes have received much attention in Texas history books, on markers, and in popular culture, comparatively less is known or appreciated about the Tonkawa. “They basically had been forgotten,” he says.

The nomadic tribe had at least 50 camps in Texas, according to Bob O’Dell, an Austin-based writer and producer who is working with Tonkawa Chief Russell Martin and director Andrew C. Richey to make a documentary on the tribe, set to release in 2025. “When early Texans saw some Tonkawa at a given site, say, near a waterfall or on a bluff by a river, they often attached the Tonkawa name to it,” O’Dell says. “They were the original Texans, after all.”

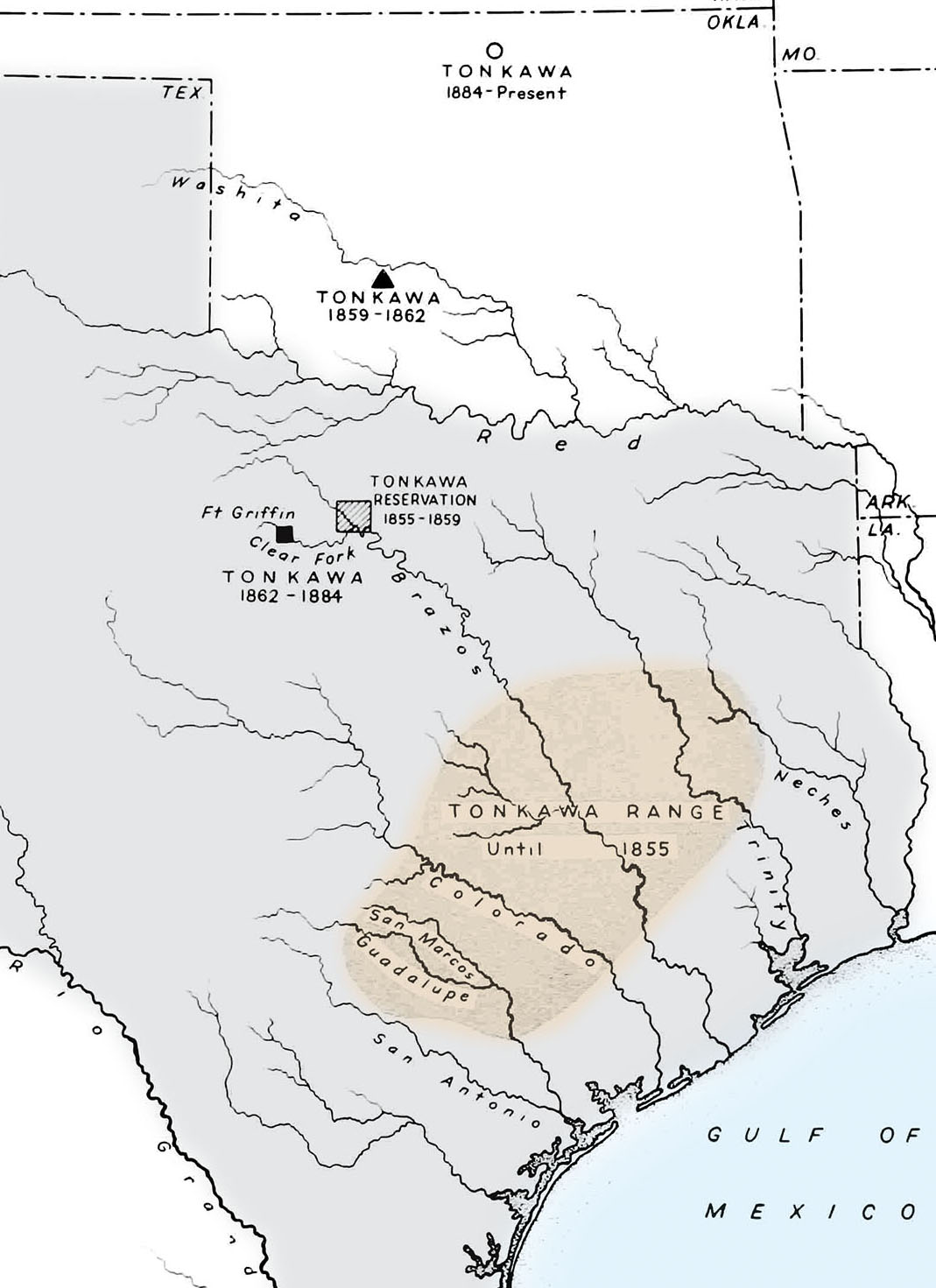

Map courtesy Smithsonian

The Waco tribe’s word “Tonkawa” translates to “they all stay together,” a fitting moniker because the tribe comprised as many as 200 small, loosely associated groups and clans related by language. Like other nomadic groups, the Tonkawa followed herds of deer and bison, which they drove off the edges of cliffs at Tonkawa Bluff outside Georgetown and east at Comanche Peak near Circleville. They also gathered fruit, nuts, and edible plants and ate fish and shellfish. At the height of their recorded population, the Tonkawa people numbered in the thousands.

French and Spanish explorers in the 16th and 17th centuries encountered scattered Tonkawa groups from the Red River to the San Antonio River, in the Brazos River basin in present-day Milam County near Rockdale, and as far east as the Neches River. The Oklahoma Historical Society points out that the Tonkawa, once believed to be indigenous to Texas, were documented in present-day Oklahoma in 1601 but were pushed southward by the Apache.

Spanish missionaries tried to convert the Tonkawa to Christianity, establishing three missions between 1746 and 1749 between the San Gabriel River and Brush Creek in Milam County. The Tonkawa “never fully accepted the missionized life as they preferred their traditional nomadic lifeways over farming, Christianity, and being subjugates of the Spanish,” David La Vere wrote in Life Among the Texas Indians: The WPA Narratives. “However, they did take advantage of the mission system when times were tough due to lack of food and supplies, or when under threat from enemy tribes,” like the Comanche.

Memorialized in Bronze

Antonio Muñoz is sculpting a bronze depiction of a Tonkawa brave. It will be installed in 2024 on Heritage Trail West, a 1-mile-long, 10-foot-wide paved trail running through Chisholm Trail and Memorial parks that depicts the history of Round Rock. “The original concept was to involve all the pieces in a sense that they relate to each other in the park,” Muñoz says. “For the Tonkawa, he is coming in, presenting a rabbit with bow in hand, which is telling the story of hunter-gatherers.” roundrocktexas.gov

The statue of Chief Plácido, sculpted by Eric Slocombe, is located at San Marcos Plaza Park, 206 N. CM Allen Parkway, San Marcos. visitsanmarcos.com

By the early 1800s, the Tonkawa returned to their Central Texas homelands between the Trinity and Colorado rivers. When Anglo settlers established an outpost in present-day Williamson County in the 1840s, the Tonkawa’s numbers had been decimated by a smallpox epidemic and wars with the Spanish and the Comanche. Their sparse clothing, body paint, and matriarchal culture made settlers uncomfortable, and in 1854, citizens from Williamson and other counties petitioned local authorities to have the Tonkawa removed. The tribe was relocated around Texas to sites including the San Marcos River, the Brazos Reservation in Young County, and Fort Griffin in Shackelford County. The Tonkawa worked with the military and the Texas Rangers as scouts against the Comanche and Kiowa. In return, they received rations of food and livestock such as goats and cows.

“The Tonkawa people were instrumental in the success of the Anglo settlers, the Texas Rangers, and the U.S. Army in the early history of Texas, and fought alongside Texans in the war of independence from Mexico,” Conklin says.

The historical marker by the bust of Chief Plácido in San Marcos states that the chief befriended the likes of Stephen F. Austin, Sam Houston, and Edward Burleson. “Texans respect the Comanche for their historic strength, but they need to respect the Tonkawa for their historic friendship,” O’Dell says. “Not the kind of friendship that just says kind words, but the kind of friendship that stepped in and saved Texans from their naiveté, strategized and led the Comanche counterattack, and once successful, smiled as we Texans took all the credit.”

During the Civil War, Tonkawa guided state and Confederate troops against the Comanche, according to Stanley S. McGowen in his 2018 book The Texas Tonkawas. In return, a coalition of Native American forces wiped out almost half the remaining Tonkawa.

Despite their assistance to Texas, the Tonkawa were not granted any land in the new republic or after Texas became a state. They eventually were banished from their own land altogether.

In September 1875, the Army cut off issues of food to the Tonkawa except for “a box of condemned hard bread,” wrote the U.S. Secretary of War, William W. Belknap, in a letter to Congress requesting help for the 119 Tonkawa barely surviving at Fort Griffin. He suggested that the Interior Department place the Indians on a reservation.

The remaining 92 Tonkawa were removed to Indian Territory in 1884, settling in Kay County in northeastern Oklahoma after a long journey by wagon on the Tonkawa Trail of Tears. Out of the 91,000 acres in Oklahoma originally set aside for the Tonkawa, they only received 11,273.

Today, the Tonkawa reservation has shrunk to approximately 1,500 acres near the town of Tonkawa about 100 miles north of Oklahoma City. Martin says “just a few” tribal members live in Texas; about 1,000 members are on the tribal roll.

Conklin says commemorating the Tonkawa’s role in Williamson County history matters, “not only to set the record straight about the past, but to resolve that we will be better,” he says. “A community that addresses the truths of its past is more likely to respect all its members, or at least be working in that direction.”