I was in London when this nightmare that we are all going through started to turn stranger and grimmer. I’d been to galleries, seen many friends, given a public reading, and even gone to the theater. Then, quickly, all was different: You could read the anxiety on people’s faces. As I walked along the South Bank by Shakespeare’s Globe, everyone on their cellphones were talking about it. The world was shutting down and I, though in my mother country, was a long way from home.

My family was supposed to join me in Edinburgh for spring break, but on March 14 I returned to Austin early to join them in self-isolation. It was a strange flight. Everyone was keeping their distance, wiping their seats, not really looking at each other. On arrival, passport control seemed quicker than ever before in Austin, contrary to other airports, where people were stuck in long queues. My wife picked me up and drove me away from all the people. Soon I was home again, and home was now the only place to be. And to think, just the night before I’d walked around St. Paul’s wondering when I’d see it again.

So, home with my two children, my wife, and quite suddenly, a small black cat who’d been rescued by a friend who was allergic to cats and who we in turn took in. So then, what to do, in the next who-knows-how-long? Virtual school for the kids, virtual teaching for my wife, but I was on leave.

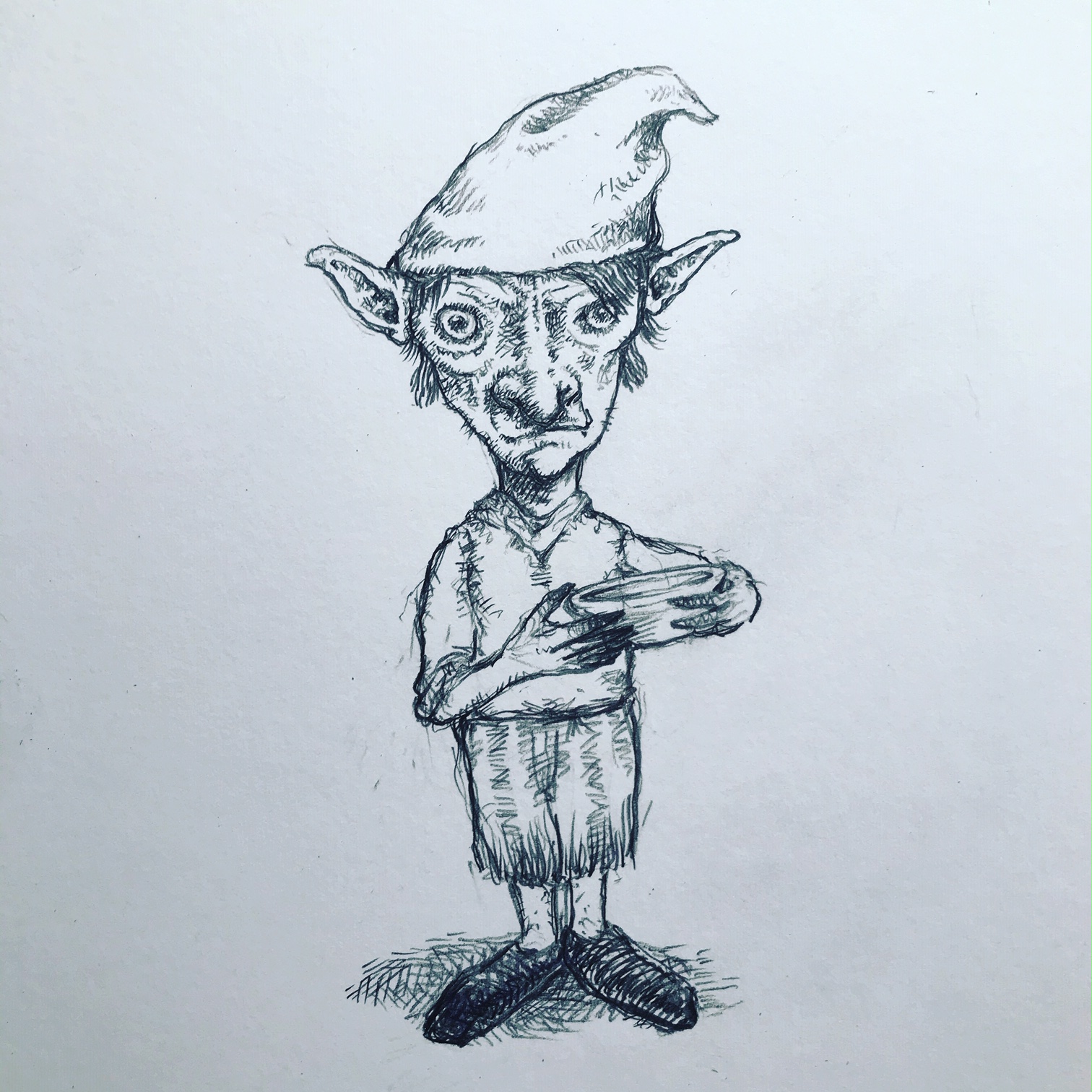

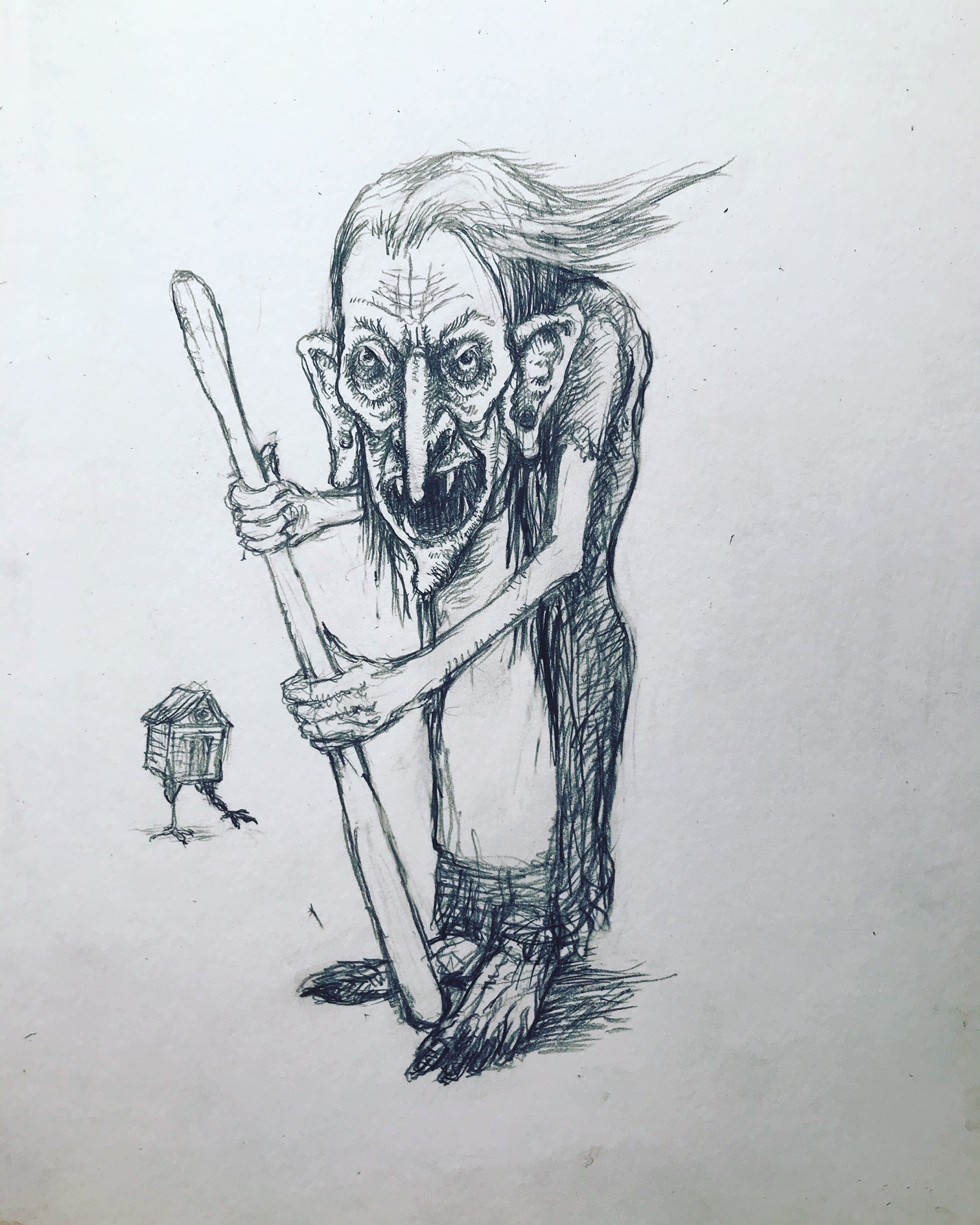

I’d recently finished a novel about an individual facing a particularly extreme form of self-isolation: Pinocchio’s father, Geppetto, who spent two years inside the belly of an enormous sea monster. I’d been thinking a great deal about isolation and what Geppetto must do to keep himself sane. First off, he must be busy, and to keep busy he writes an account of his life. He must also make art because, above all else, Geppetto was an artist. So, for the book I made the art that I supposed Geppetto would make while imprisoned inside the whale.

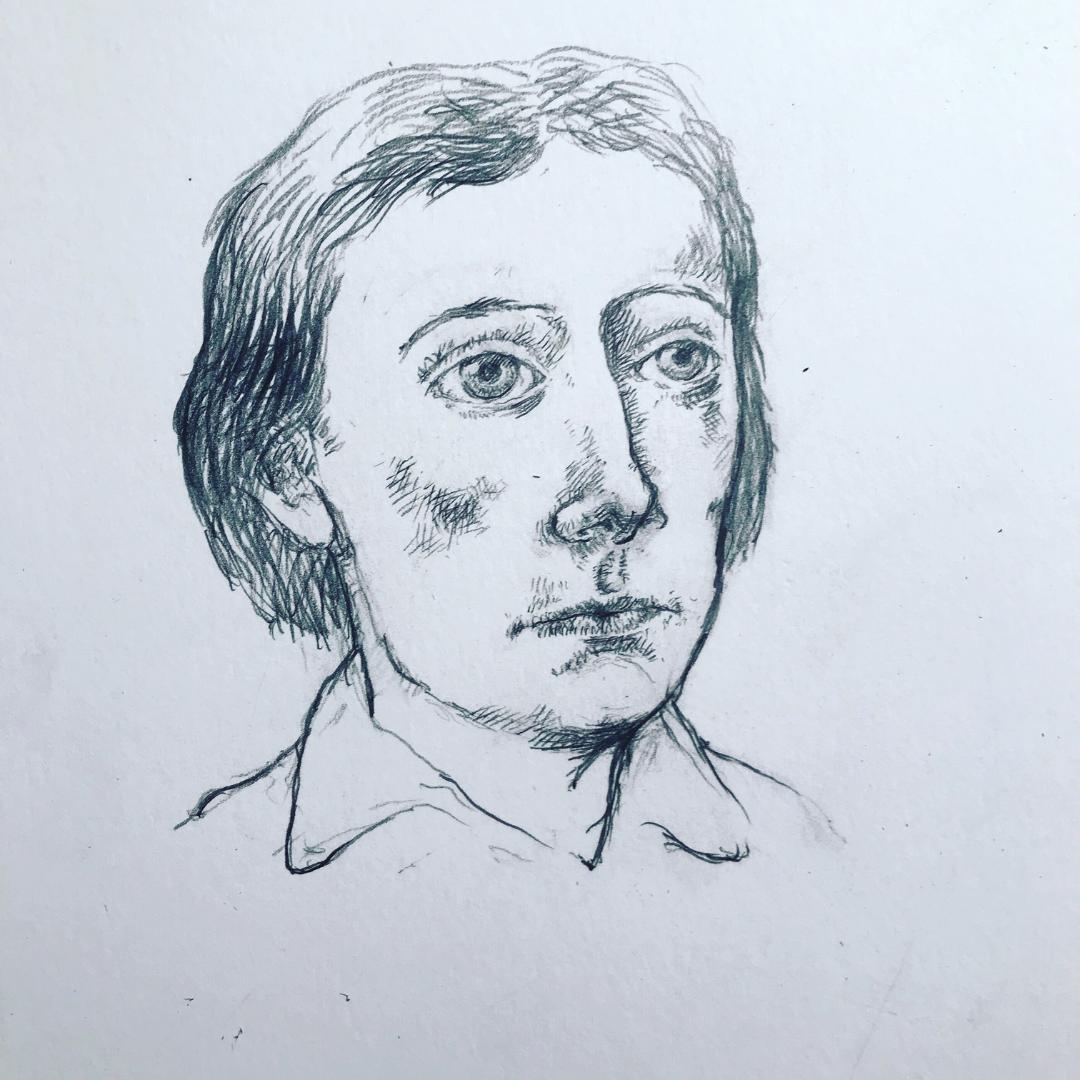

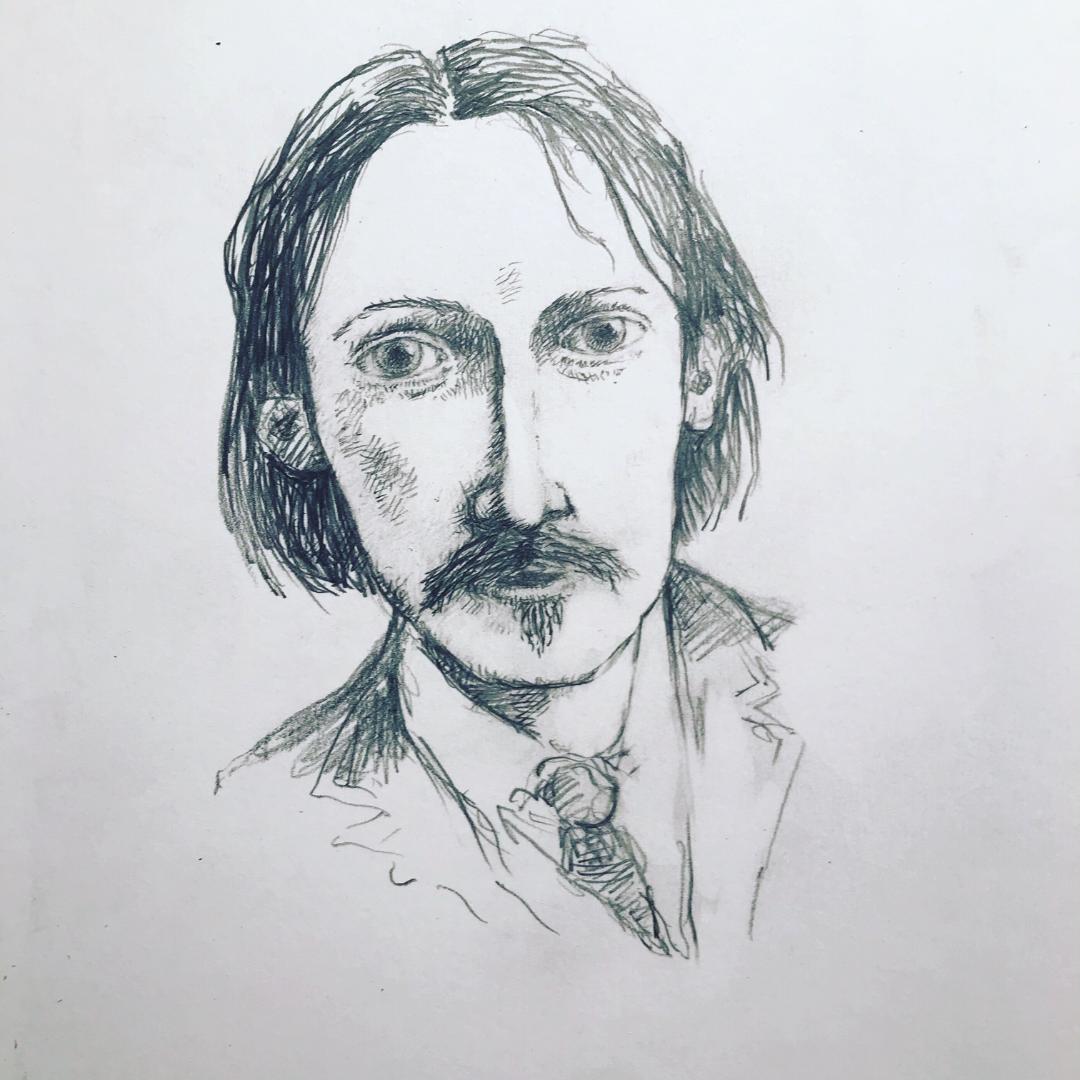

Back in Austin, I wondered what on earth I could do now in the coming weeks and months. I did not want to continue with the novel I was writing; it is set in a children’s hospital and felt too bleak to be writing just now. There was another book I was thinking of writing and had been mulling over for a few months, so perhaps I’d start on that. But I needed something to do instantly, and so I got out pencil and pad and drew a determined looking young man. There, I thought, that’s a start.

Click the image above to view all of Carey’s drawings and descriptions

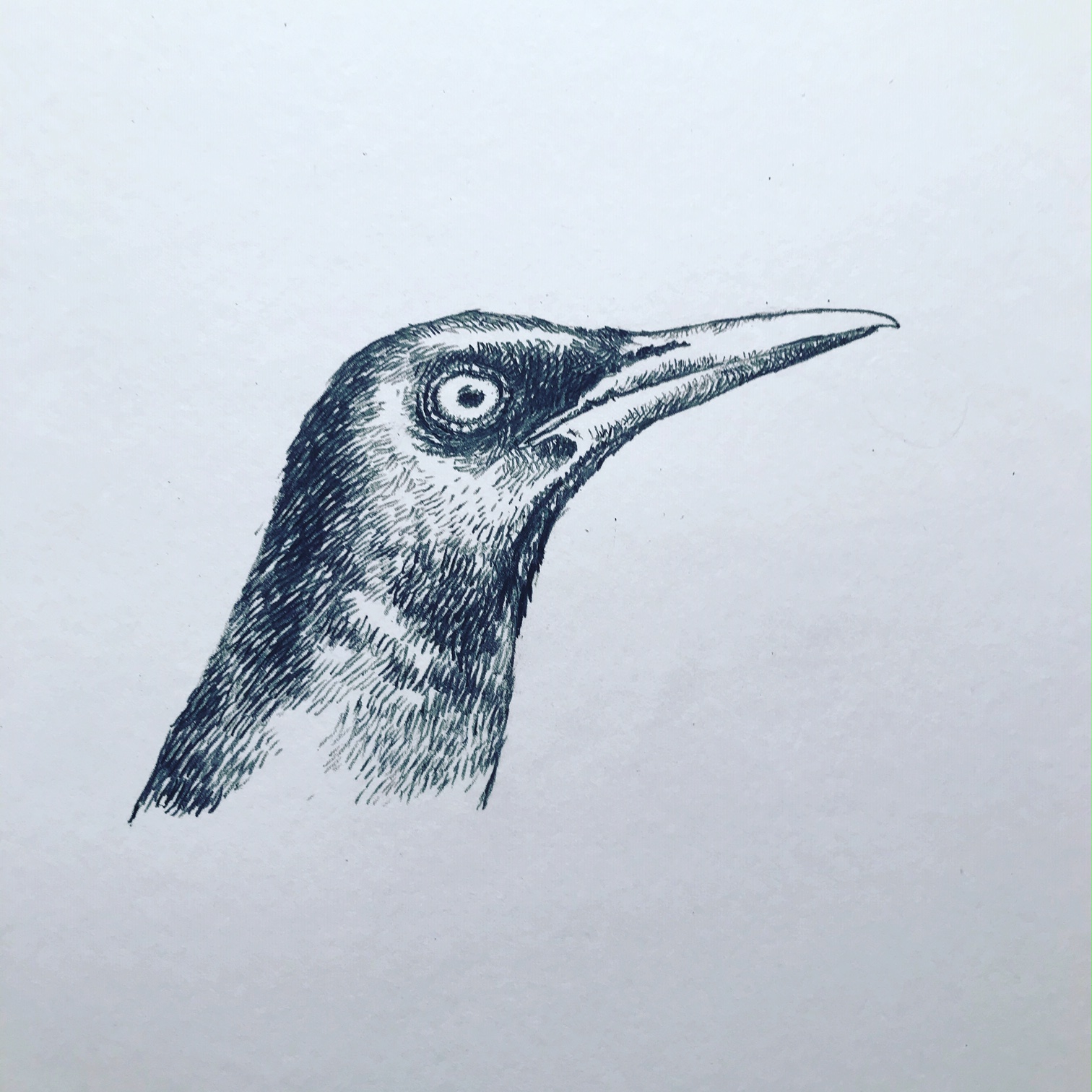

There is something so comforting about a blank piece of paper and the lines the pencil can make upon it. The pencil is such a humble object but such a versatile one: It can make very faint marks or the blackest black. It is also very forgiving: If you make a mistake, you can rub it out. A pencil can be anything, and drawing requires no great setup—just a piece of paper and a sharpener, and then it can be kings or trolls, philosophers or grackles.

I post my drawings on Twitter, and as I posted the one of the young man, I declared without really meaning to, without really giving the matter much thought, that I would do a drawing every day until we were allowed to be with each other again. That seemed easy enough, and it would provide at least a small piece of structure to my day. A drawing a day is, after all, not so very much.

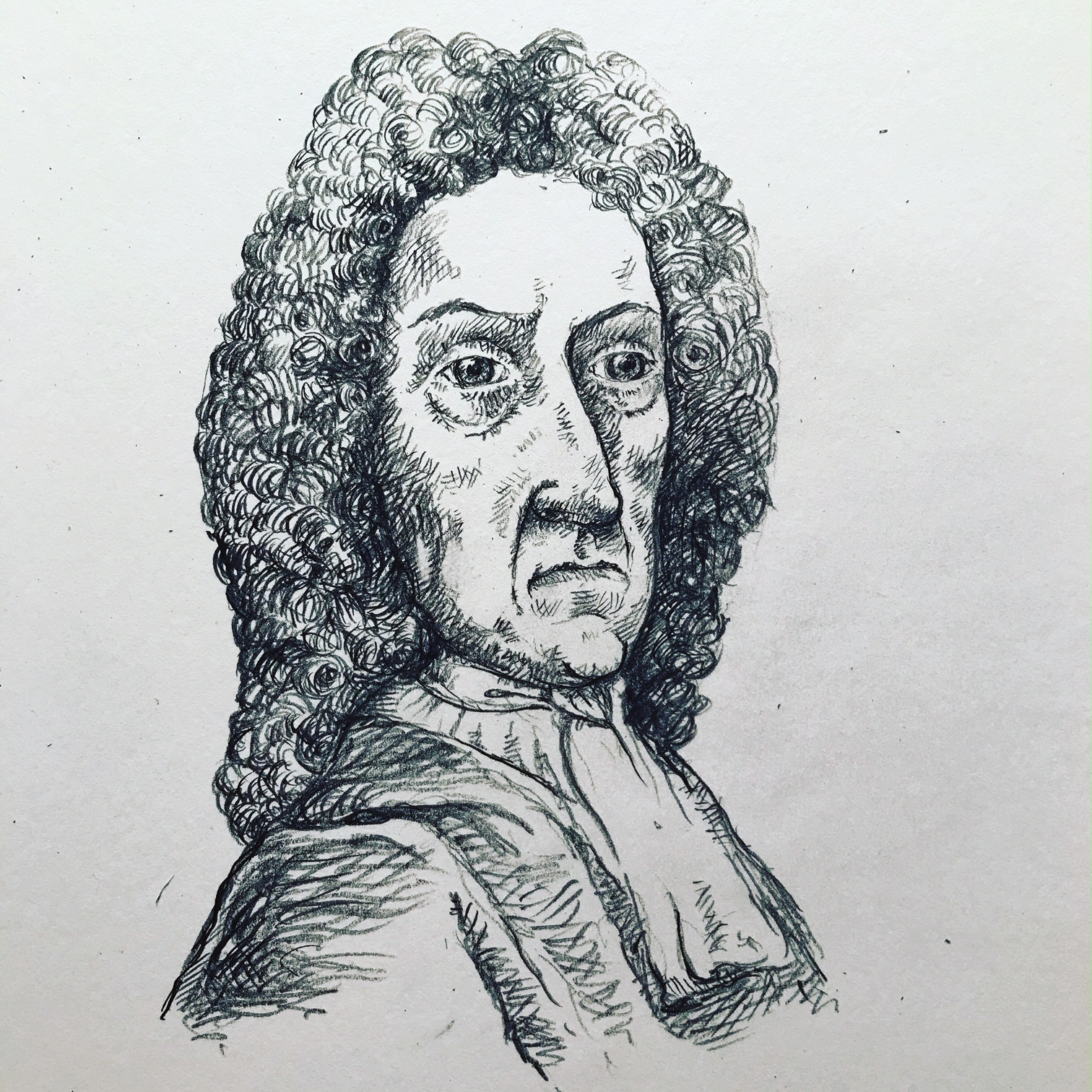

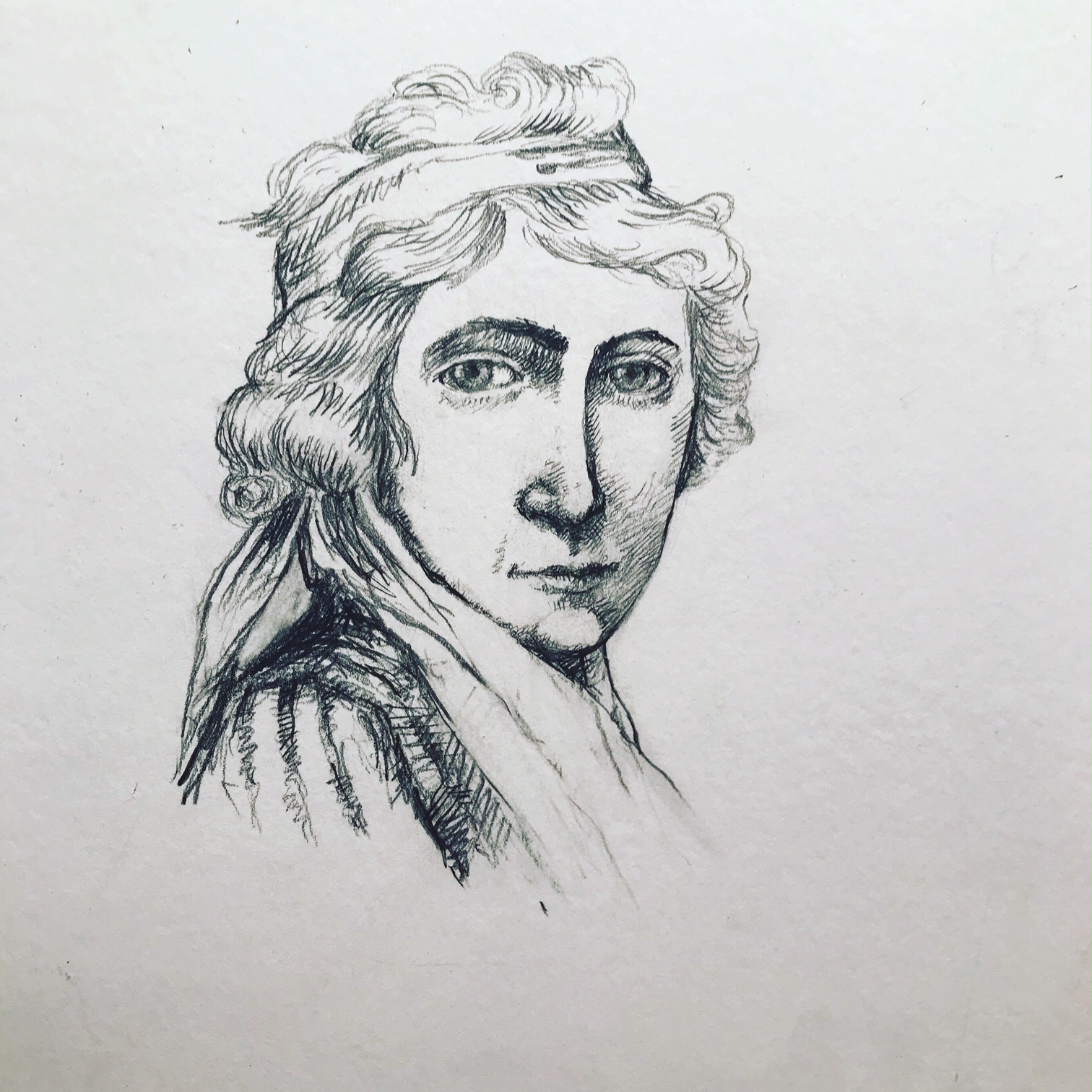

Very soon the question for me became what to draw next. The second day was a determined young woman, and then a grackle because I love grackles, and then the cat that’s staying with us. But each morning I would scratch my head and wonder what to draw that day. I did Samuel Pepys because I missed London. A friend quarantined in an apartment in Rome asked me to draw Daniel Dafoe because, like Pepys, Dafoe witnessed the Great Plague in the British capital.

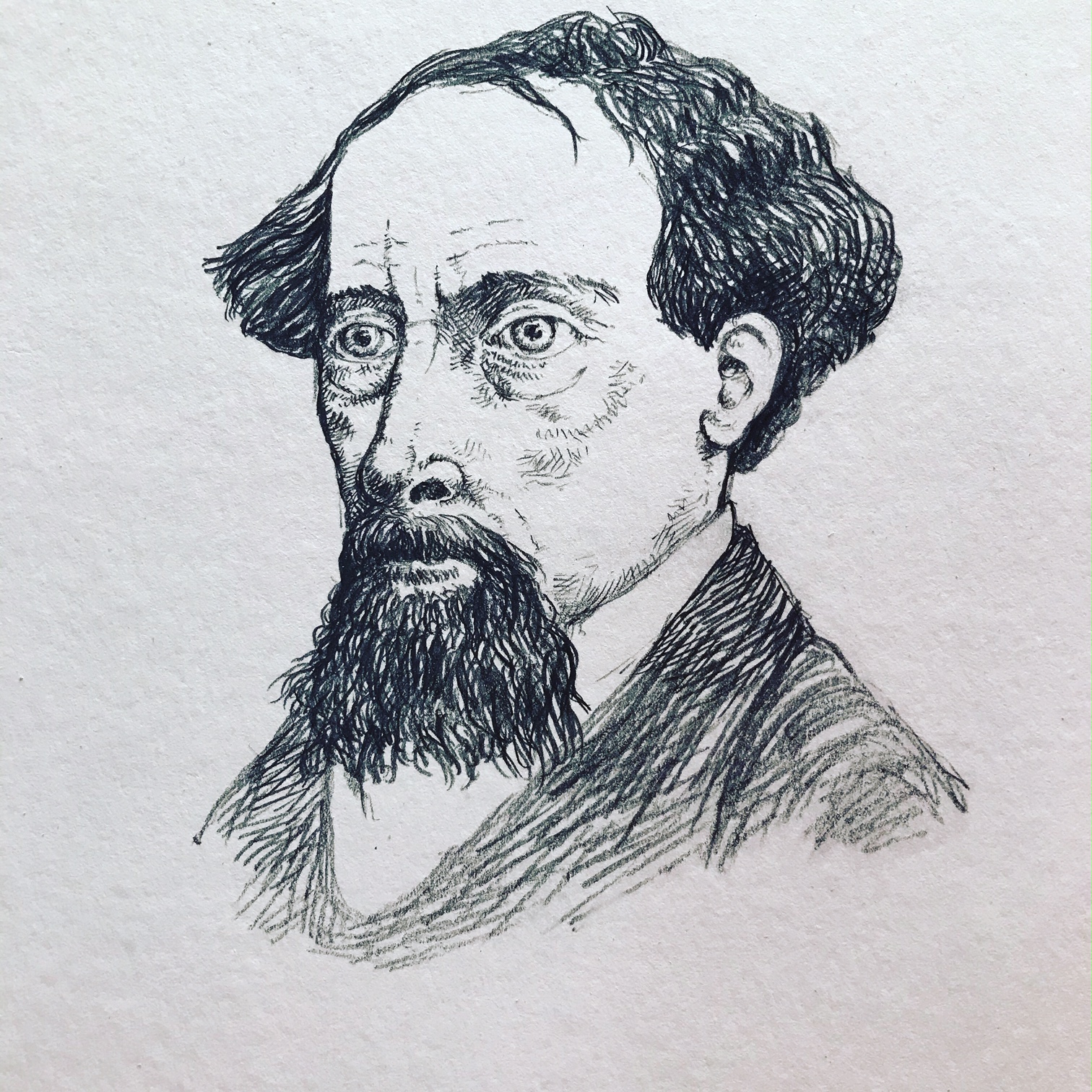

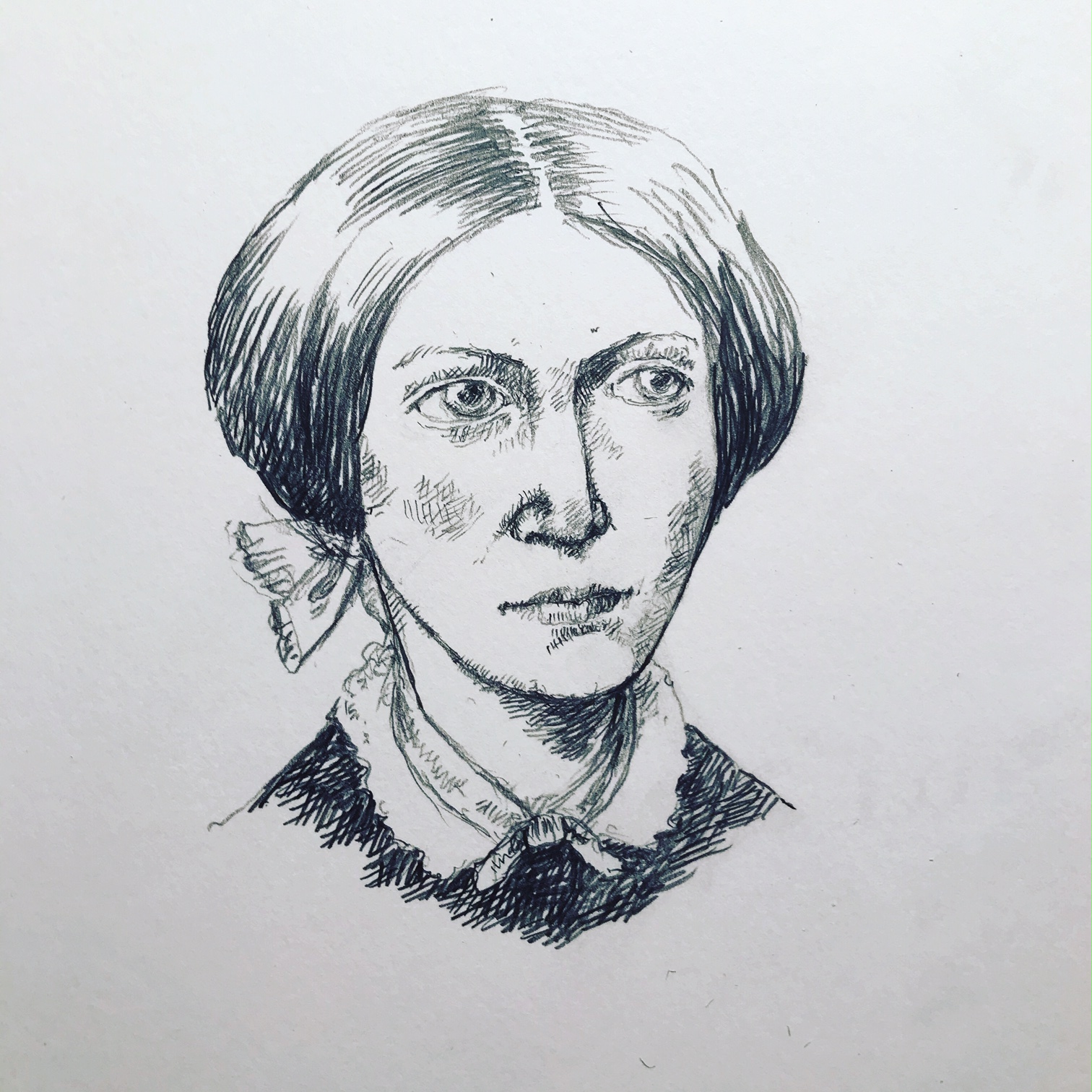

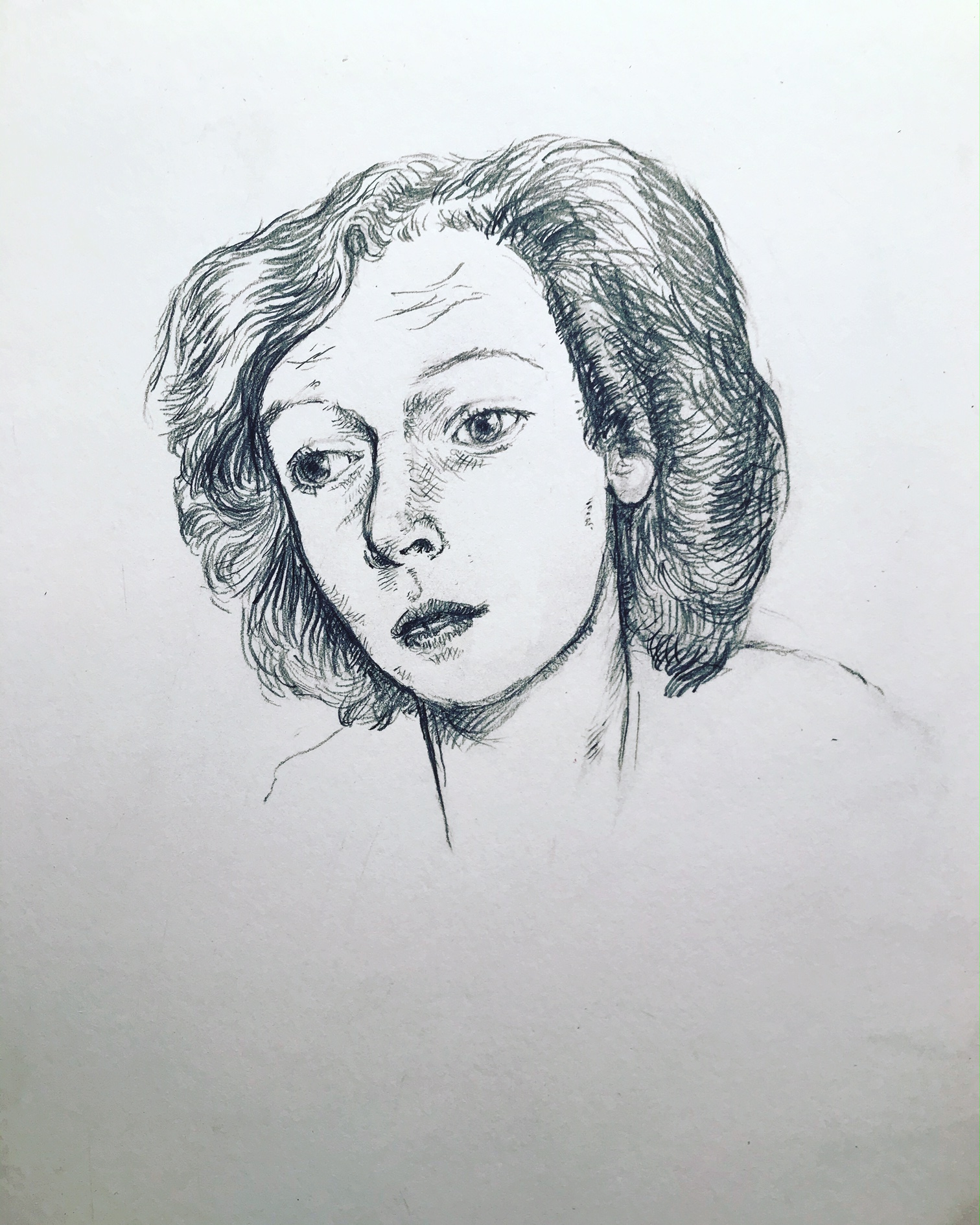

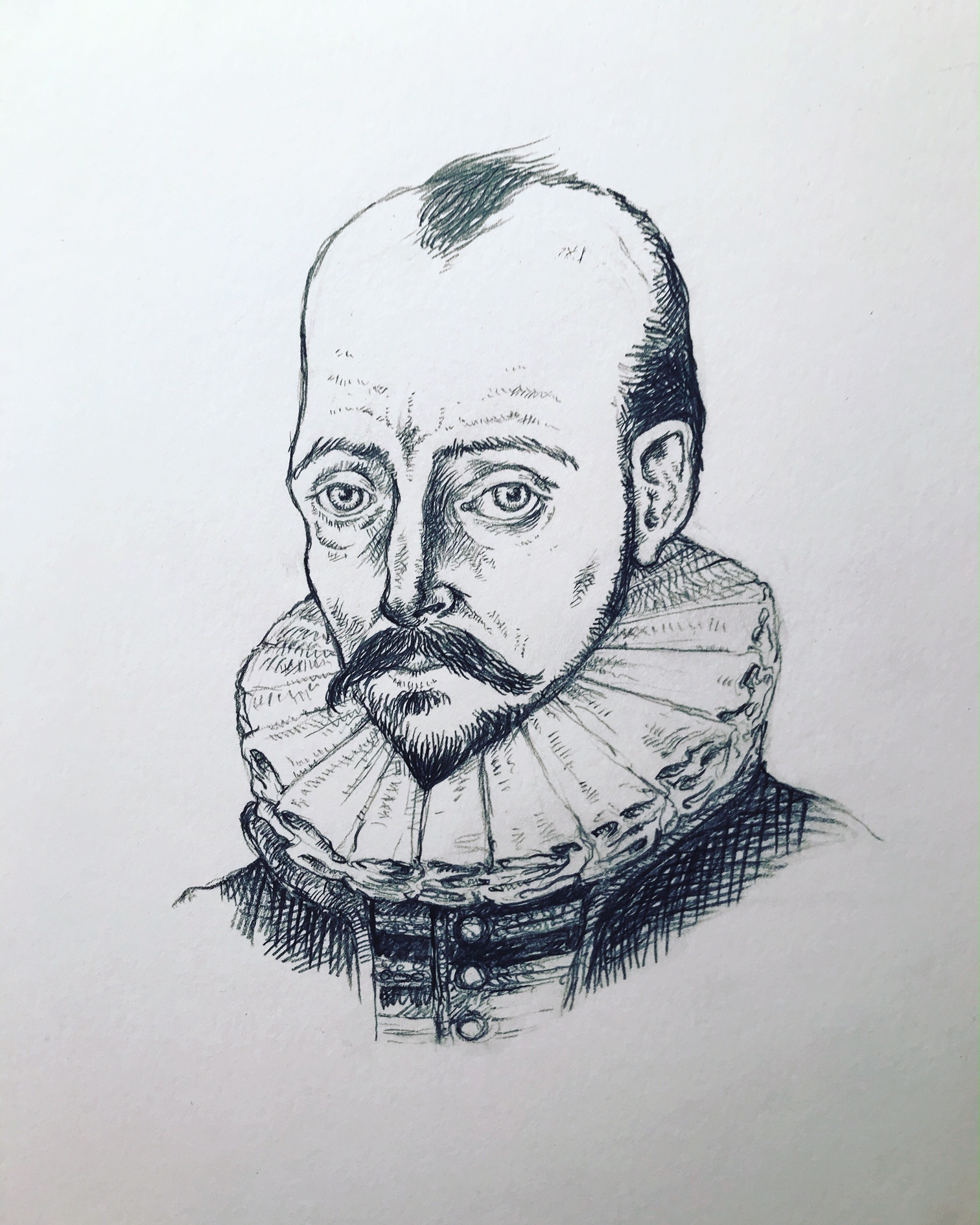

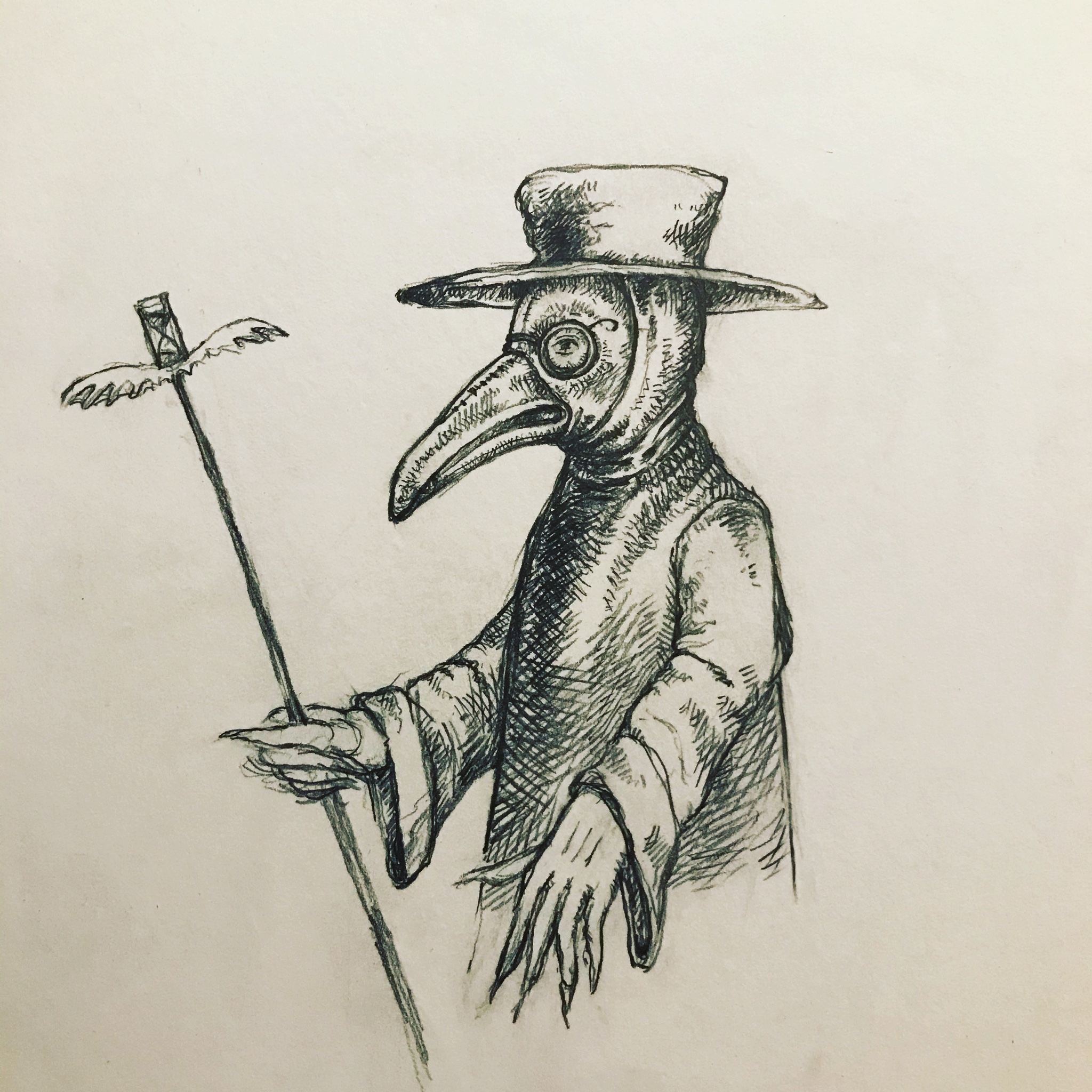

After that, other people started putting in requests. There were requests from people I’d never actually met, and so I found myself drawing people or animals I’d never otherwise illustrate. Along came a magpie and a goat (Great Orme goats, taking advantage of the lack of people on the streets, wandered casually from the countryside into the Welsh town of Llandudno). Then came characters from Shakespeare: King Lear and Richard II. Then writers: Mary Wollstonecraft and Virginia Woolf. Characters from mythology or folklore emerged: Medusa, a brownie, Puss in Boots, Baba Yaga, Pesta (an old hag in Norwegian folktales who is the embodiment of the Black Death), and a plague doctor. Also, more great minds to help us in this strange isolation: Michael de Montaigne, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Robert Louis Stevenson.

I post the drawings every day, sending a little message in pencil. It’s my small way of communicating with people during this isolating time. Sometimes I don’t like the drawings particularly, but I’ve made a commitment to this so I post one a day without fail. I like hearing from people and seeing other people’s drawings. I feel brief connections, small waves. It’s not much, but it’s something. People keep mentioning how Shakespeare wrote King Lear while quarantined during a plague, and that we must use this time efficiently and energetically and above all not waste it. But I don’t really hold to that. I think we can be kinder to ourselves, take it easy, do things for the love of it, don’t flog yourself.

Tonight, I will sit down and draw the twenty-seventh drawing of this quarantine and I suspect it will be Florence Nightingale. I draw now what people ask for (with the exception of a self-portrait on my fiftieth birthday), and I like that. It takes me somewhere different, and we all need to find new destinations during this time of shelter. I’ve no idea what drawings will follow, nor how many drawings will be stacked up by the end of this. I’m just taking it—like so many people around the globe—one day at a time. One drawing at a time. A drawing a day to keep the eye off the plague.