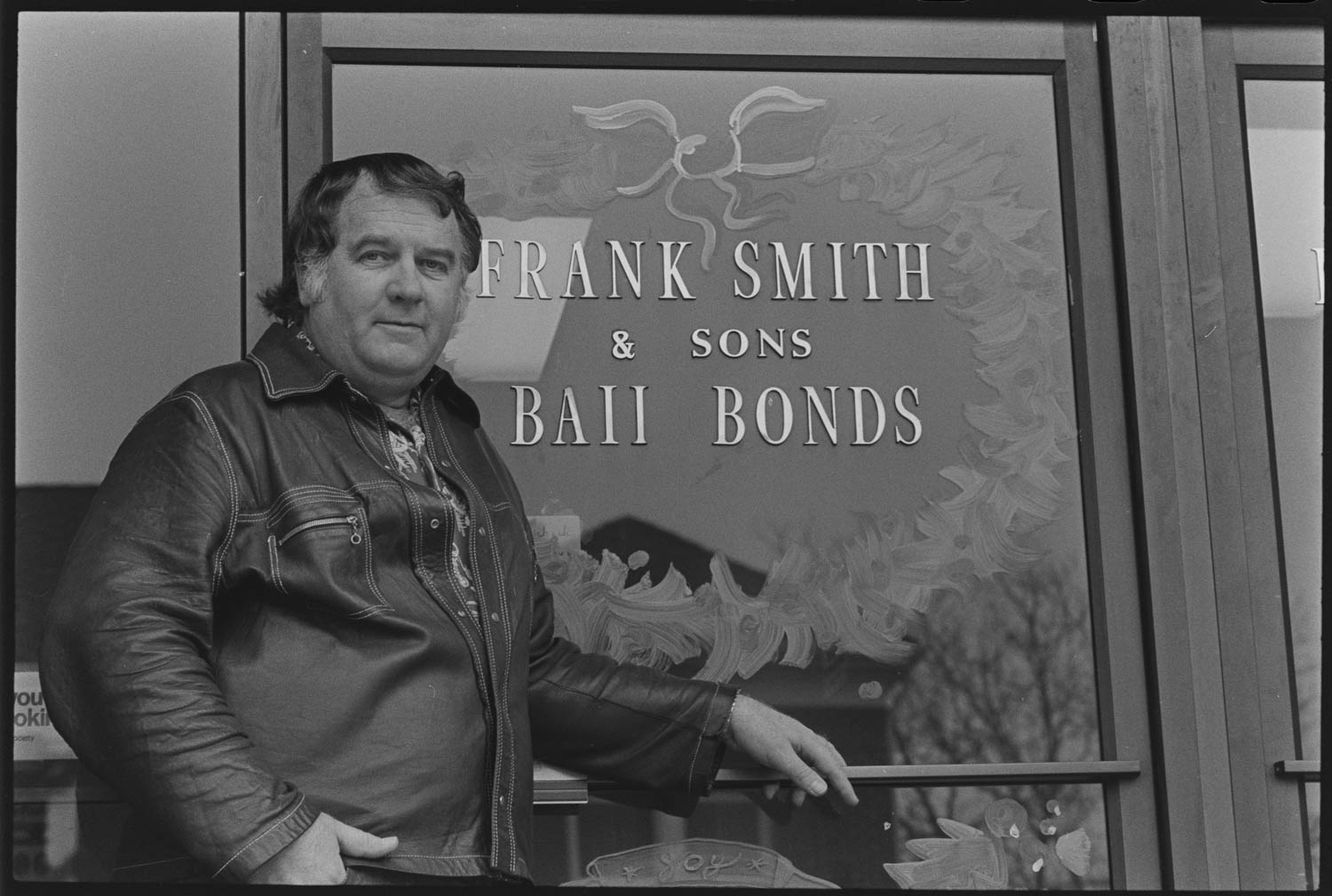

Frank Smith went from a preacher’s son to one of Austin’s most notorious criminals. Courtesy University of Texas Press.

When I was gigging regularly in bands in Austin and elsewhere in the 1970s, I would daydream I was a character in a black-and-white movie, playing in nightclubs that were fronts for underworld characters, where criminal plots were hatched backstage and crime bosses conducted business over cocktails. Some of those fantasies were inspired in part by real characters and actual events. Eventually, I channeled my curiosity about film noir and detective fiction into a novel set in Austin, featuring a bass-playing part-time detective named Martin Fender. Rock Critic Murders, published in 1989, starred the real-life haunts of my alter ego, with many scenes set at music venues like the Continental Club and Antone’s. Two follow-up novels, Tough Baby and Boiled in Concrete, revisited the same territory, elevating my interest into an obsession.

Last Gangster in Austin covers the capital’s city crime scene during the 1970s. Courtesy University of Texas Press.

I used to love writing crime novels, but eventually I realized I loved writing nonfiction more. I enjoy the research, unearthing facts and details, and weaving it all into an entertaining narrative. My new book, Last Gangster in Austin: Frank Smith, Ronnie Earle, and the End of a Junkyard Mafia, out this month on University of Texas Press, takes readers back to Austin in the mid-’70s, when Esther’s Follies and Armadillo World Headquarters were going strong (see my books Esther’s Follies: The Laughs, the Gossip, and the Story Behind Texas’ Most Celebrated Comedy Troupe and Armadillo World Headquarters: A Memoir, written with Eddie Wilson). Back then, outbreaks of violence often leaned more toward Austin’s dusty, frontier past than its gleaming, high-tech future.

Take Last Gangster’s inciting incident: On December 3, 1976, three masked, armed men stormed the chicken coop office at Austin Salvage Pool, a junkyard brokerage on Dalton Lane in a desolate, rural industrial area on the southeastern outskirts of Austin. The bandits arrived right after the departure of Frank Smith, who had just paid $15,000 for a collection of wrecked cars. The first robber through the door demanded the money and opened fire. Six people were inside. The owner, Ike Rabb, grabbed a 20-gauge shotgun and fired two fatal blasts at the robber. The other two robbers escaped but were later captured. Bill Cryer, who reported the story for the Austin American-Statesman, told me it was obvious to all that Smith, who had been harassing Rabb with Mafia-style tactics for years, had hired the robbers to steal his money back.

The son of a Baptist preacher from Waco, Smith was a larger-than-life character who craved attention and could alternate between charity and brutality without a blink. He liked giving reporters like Cryer tours of his massive wrecking yard just north of Austin city limits, pausing before the car-crushing machine for a reminder: I could put a man in that car and crush it and the body would never be found. The man who put an end to Smith’s criminal career was Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle, who devoted all his powers during his first term to shutting down Smith’s bail bond empire and sending him to prison for life as a habitual criminal.

I started writing this book just as the COVID-19 lockdown started in March 2020. I had been collecting research files on the subject for almost two decades, but to my misfortune I had never gotten around to interviewing Earle. He passed away two weeks after I started working on my outline and making phone calls. Fortunately, his wife, Twila Earle, supported the project and became an invaluable resource. Cryer and others were also enthusiastic contributors. All the interviews were done by phone and email.

Perhaps because of the lack of face-to-face interaction, plus the fact that I moved to Los Angeles last February, I’ve been craving the prospect of revisiting some of the locations mentioned in the book. Smith’s bail bond office was conveniently located on the other side of Guadalupe Street from the Travis County Courthouse. Formerly called the Stokes Building, it is currently known as the Travis County Ned Granger Administration Building. Granger, the former county attorney, was an old crony of Smith’s.

Jesse Sublett has written several books and is the former frontman for the seminal Austin rock band the Skunks. Courtesy Jesse Sublett.

Readers of my book may find it difficult to sympathize with Smith, but longtime Austinites may wax nostalgic for the eateries where he took meetings with various gunsels from the Austin and Fort Worth underworld. Fortunately, the Original Hoffbrau Steakhouse is still in existence (though closed for the summer), as is El Patio, a quirky Tex-Mex favorite on the Drag. Smith also loved Piccadilly Cafeteria in Capital Plaza and Night Hawk Steakhouse, both long since departed. Another of Smith’s favorites, The Sisters Chinese Restaurant on Burnet Road, was operated by the mother and aunt of Ronald Cheng, who continues the family tradition with Chinatown, a fine-dining establishment with multiple locations in Austin. During the two weeks after Smith’s indictment on armed robbery charges, his dutiful office manager, Dottie Ross, would pick up meals from these places and deliver them to the motel where he was hiding out.

Elsewhere, two East Sixth Street dives, JJJ’s Tavern and Sun Theater, were home base for John Calvin Bailey, the junkie poet who provided damning testimony against Smith. These sites, which enjoyed long and eventful lives going back to the vaudeville era, have since come full circle as homes to Esther’s Follies and the comedy club Velveeta Room. I guess the joke’s on Smith.