School’s Out

A journalist and mother finds herself in the story of Texas

by Sindya Bhanoo

The drive from Austin to East Texas took me nearly five hours. After I made my way through Houston traffic, the world began to quiet. Thick forests of tall pine trees flanked me on both sides of US 190. It was beautiful, desolate in parts, and unlike anything I’d seen in Texas. I drank in the silence. For months I’d been home with my children 24/7. It was 2021 and we were deep into the pandemic. I was on my way to Jasper to report on the digital divide and how it was affecting rural students. I spoke in advance with a dozen teachers, administrators, and parents. The Jasper school superintendent said the situation was dire. He wanted the rest of the state to know students in rural Texas were struggling.

I’d been living in Texas for more than four years, but this was my first time visiting any place east of Houston. I associated East Texas with Bernie, the Richard Linklater black comedy crime film. I knew Jasper only for the brutal 1998 murder of James Byrd Jr. by white supremacists. I knew, too, that COVID-19 vaccination rates in East Texas counties lagged behind the rest of the state.

These days, I mostly write fiction, but I have been a news reporter for nearly 20 years, and I take the work seriously. Over the years, assignments have taken me across the country and around the world, onto fishing boats in Long Island and into the homes of Amish farmers in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. I’ve gone hundreds of feet underground into a coal mine in India and walked through the wards of hospitals in Denmark. It has been a great privilege to enter the lives of others, to sit and listen to their stories and then share them with the world. Early on, I was trained by editors at two newspapers of record to report and write with integrity, to ask tough questions while being respectful, and to always maintain distance. Newspaper reporters do not personally solve the problems of those they interview, nor do they give or receive gifts. Neutrality is important. Interview subjects do not become friends. Reporters tell the story. That’s the work, the public service.

I have followed these rules religiously, and I am proud of the work I’ve done. But something shifted during the pandemic, talking to students in Jasper, school bus drivers in San Antonio, mothers in the Rio Grande Valley, and school administrators in Odessa. It was the first time I felt like I was part of the story I was reporting. The distance between me and my sources, and my audience, collapsed. It was hard to work and impossible not to. The unknowns of the crisis, the swiftness of its arrival, and the brutality of it all appealed to my reporting instincts.

One of my first pandemic stories was about how to select a well-fitting mask. After the piece was published in The Washington Post, I emerged from my home office to find my husband sitting at our sewing machine, cutting up old fabric and following a mask pattern he’d found on the internet.

The pandemic took hold of America, just as it took hold of the world. My 8-year-old daughter finished third grade on Zoom. My 4-year-old son’s preschool shut down. Thousands of miles away in India, my cousins went through the same thing with their kids. My husband and I still had to work. To amuse himself, our preschooler started climbing the doorways of our house in Central Austin. He started letting his legs hang loose and counting. At his peak, he could hold himself up for three minutes with his arms alone. At one point, desperate for company and unable to get lost in books the way his older sister could, he started catching flies in the cup of his hand and naming them. He called them his pets.

It was not an easy time for our family, and in some ways, we are still recovering. My kids had always gotten along, but cooped up with only one another as playmates, they began to bicker endlessly. It began each morning before they even brushed their teeth. My patience wore thin. Sometimes I tried to mediate. Sometimes I left the room. “Sort it out yourselves,” I’d say as calmly as I could before retreating. Other times, unable to control the tension swiftly rising in my head, I shouted.

My husband and I made good pandemic teammates, but it felt like we were always working. There was never time to breathe. The news was hopeless. The death count was rising rapidly. Every night I fell asleep drained, with the growing sense that it might be years before normalcy returned. I was tired of cooking. I was tired of cleaning. I was tired of being home. I was tired of the squabbles. I was just plain tired, and there was no end in sight.

We tried to keep our spirits up by taking bike rides to parks. Realizing how vital this outside time was, my husband sometimes shook the kids awake early so we could beat the late morning heat. We packed a tennis ball and Frisbee for catch, sought out shade, and had some old-fashioned fun. Often, we went to Adams-Hemphill Park, a 10-acre neighborhood park in the center of the city, and afterward, picked up buttery croissants from Texas French Bread, our favorite neighborhood destination before the pandemic. I entertained the kids by spinning extravagant stories about two young siblings named Akash and Leela, who built an international franchise of bookstores, became billionaires, dropped out of school, and then rejoined school because they were bored. I have forgotten the details of the tale, but my children recount them readily.

I missed my parents, who live in Atlanta, Georgia, immensely. I was desperate to be with them, for the comfort only parents can offer. Normally, one good dose of them filled me up and sustained me for months, but I would not see them for almost one year.

Our friends in Austin and beyond had their own struggles. Kids we know fell behind with schoolwork. Some struggled with depression. Some were overeating, or undereating. Some moved back to their hometowns to be closer to family.

As I documented the incredible challenges those outside of my personal network were facing across the state through my reporting, I quickly came to understand, in a visceral way, that although the pandemic was not easy for anyone, we all experienced it in different ways. How we experienced it largely depended on the resources we had.

Months before I went to Jasper, I visited San Antonio for two stories in the fall of 2020. I shadowed a hospital custodian as part of a national series for The Washington Post on essential workers, and I did a ride-along with a bus driver who was delivering meals to students for a Texas Monthly article. These trips marked the start of my in-person reporting during the pandemic. Until then, I had done everything on the phone and on Zoom. In San Antonio, I met with bus drivers who, as the first and last people to see students every day, understood how reliant some kids were on those meals. In the San Antonio Independent School District, a great percentage of children come from economically disadvantaged families. Drivers pitched a program that used buses to deliver meals to children who attended school online.

On my ride-along through a largely working-class Hispanic neighborhood, I met a married couple, both disabled and in their mid-80s, who were caring for their seven great-grandchildren. The parents and grandparents of the children were all working and relied on the oldest generation for child care. It was clear the great-grandparents were doing the best they could, but they were overworked and under-resourced, and online school was difficult for them to navigate. I drove home with the faces of the children, all between 3 and 11 years old, buzzing in my head. I thought of the famous Nelson Mandela quote: “There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.”

In the fall of 2020, my husband and I made the decision not to send our kids to school at all. We didn’t feel that in-person school was safe, and we did not want the kids on Zoom for hours. I felt it would be particularly hard on our son, who was supposed to be in kindergarten. Instead, we set up a little home-school. On Sunday evenings, we hurriedly put together a schedule for the week. We were not trained teachers, but we had experience in other areas, and we figured it was a unique opportunity to teach the kids what we knew.

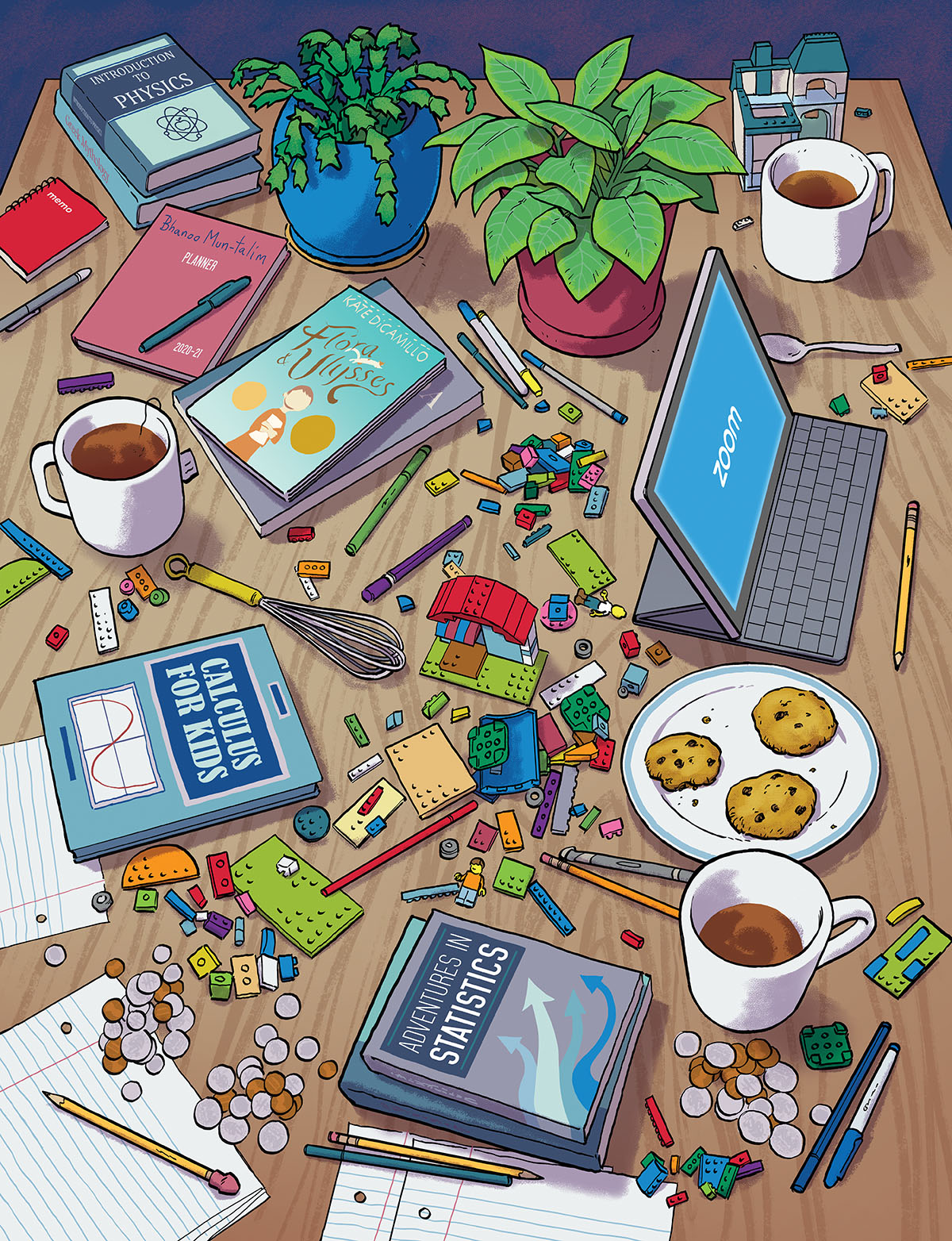

Mostly, I think our kids will have fond memories of the time. My husband, who is a software engineer, named the school “Bhanoo Mun-talim.” Talim means “mind gym” in Marathi, the Indian language his family speaks. In the morning, the children looked forward to “Baba Lectures” from him. They discussed topics in statistics, calculus, and physics. The lectures always had a hands-on component. They used all sorts of objects around the house: Legos, kitchen utensils, plants, coins. Every morning, they did math with Bach’s “Cello Suites” playing in the background. Sometimes they did a little computer programming. Twice a week, my mother gave the kids Tamil lessons on Zoom. My parents speak the language, but before the pandemic the kids never had the opportunity to learn it. The kids and I had a weekly book club. I read to my son; my daughter read on her own. On Thursday afternoons we drank chamomile tea, ate cookies, and discussed chapters of Flora & Ulysses by Kate DiCamillo and All-of-a-Kind Family by Sydney Taylor.

They produced a weekly news show using my phone that we edited together and shared with my family on a private YouTube channel. We read The New York Times every day, watched PBS NewsHour, and discussed important events. We studied the Amazon rainforest and made dioramas. I had my daughter do a project on refugees, and she interviewed immigrants from Senegal and Vietnam over Zoom. She wanted to study the life of Mahatma Gandhi, so she did a project on him and a Zoom presentation for our extended family.

Importantly, they also had a lot of time to play. When you only have two students, a day’s worth of schoolwork can be done much more efficiently. Between the two of us, we were able to offer the kids a custom experience for a short time. But it was exhausting and unsustainable, and I hope to never do it again.

In the peaceful moments when the kids were doing math, Yo-Yo Ma’s rich, warm tone in the background, I was often making phone calls and writing at a frenetic pace, gathering information about children who were decidedly not spending their school year in the same way. One morning, as my children worked, I interviewed a mother who lived in a substandard housing development called a colonia outside of McAllen. She only spoke Spanish, so there was a translator on the line. She signed up for internet service so her kids could do online school. She had a $70 balance she was still trying to pay. Her husband worked at a meat processing plant and until the pandemic started, she worked at a seafood restaurant. Now she was home with the kids.

“I’m having a hard time paying the monthly bill,” she said. “If this didn’t happen, we wouldn’t have internet.”

“It’s hard. I understand,” I replied. Then I corrected myself. “I am so sorry.”

In the evenings, we cooked together—no matter what. Before the pandemic, my husband traveled at least once a month for work, but now he was with us every night. He picked up sourdough starter from Easy Tiger and started making homemade pizza on Saturday nights. He baked blueberry scones. I started making traditional South Indian food that I did not have time for pre-pandemic. I ground and fermented idli and dosa batter as my grandmothers and great-grandmother in India did and, for the first time, figured out how to roll rotis that puffed up gloriously on the griddle.

The kids started chess and Rubik’s Cube lessons online. We pulled board games out of the closet that had been collecting dust. We often went to Austin Tennis Center and hit balls late into the evening. During the four years prior, we never stayed out late. The kids were young, our mornings started early, and we were always racing to get dinner, showers, and bedtime done. Now, though, we could stay out late and get up late if we wanted. There were no morning bells or tardy slips. On the court, we fed the kids balls and then split ourselves onto two courts, kids on one and us on the other. I was awful, but I also felt like I did when I was 16, hitting for hours with my friend Heather, the cool air ballooning through my shirt, the magical effect of the floodlights transforming me into a star.

We went further, too, to places in Texas we’d never been to before: Georgetown, Mason, Galveston, Marfa. In Galveston, we roamed through the interior of an old steam train before heading to the beach, where the kids set up a seashell and rock shop in the sand. In Mason, we biked to the fort, where we peeked into the officers’ quarters and learned about the time Robert E. Lee spent there. Our daughter was supposed to be in fourth grade, a year when students study Texas history. She was anxious about missing out on this and sorry not to build a model of La Belle like her classmates, but we covered history in our own way that year.

Over the course of my childhood and adult life, I have lived in 16 cities in nine states. I have never spent more than six years in a single place. I’ve never bothered making places utterly my own, mostly because I have always come to anticipate a move. Why decorate walls when things will soon need to be taken down anyway? Hometown is not a word that means anything to me.

In Jasper, nearly everyone I met was from East Texas. Home, it felt like, had always been home. The superintendent was a Jasper native and a graduate of the local schools. Many of the children I interviewed had grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins nearby. A retired banker led the charge to bring high-speed internet to the area, for students and to improve job opportunities. He told me he thinks his people are treated differently because of their location behind the Pine Curtain. He was determined to see change within his lifetime, and he was working with other activists and politicians to make this happen. I admired his grit and passion. I wondered if I would ever feel such loyalty to a place and its people.

When I moved to Texas in 2016, I didn’t intend to make it my home. For the first three years, I maintained a small radius. I came to Texas to write, not to see Texas. I moved from Northern California and, upon arrival, was offended by the July weather and inferior produce. I was there to do my MFA at the University of Texas’ Michener Center for Writers, and because I had two young kids and a husband who traveled for work a couple times a month, I wanted to keep life as simple as possible. We lived down the street from the Dobie House, the center of the Michener universe. My daily commute to campus was a five-minute walk through a little park with an Eeyore statue. My daughter’s elementary school was around the corner, and my son’s preschool was a three-minute drive from our house. It was a pleasant life, but for me a temporary home while I tried to figure out my writing.

While at the Michener Center, I diligently worked on a short story collection. I developed a regular writing practice and, for the first time, saw myself as a creative writer. But once the pandemic hit, I was unable to write a word of fiction. The world was collapsing around me, and it felt important to stay in my home and take care of the people I loved. I also, for the first time in years, felt a need to return to journalism. It was the pandemic, finally, that pushed me to make my house in Austin my home and see Texas for the varied state that it is.

In Jasper, I drove up and down county roads to interview students and families. I met a high school senior and football star who did not have reliable internet in his country home. Sometimes, he was able to use his cell phone along with a signal booster, but most days he was a Wi-Fi nomad. He parked outside of Walmart or Lowe’s or McDonald’s with his sister and sat in his car for hours doing his homework. Six weeks into his senior year, he was failing all his classes. His father was worried he might not graduate. I met a teenager with a congenital heart condition who could not return to in-person school. I drove further out, down Farm-to-Market Road 1408, and turned onto a small, dusty road where I met a mother of three who had stage 4 Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She had her three young kids seated at the kitchen table in their single-wide trailer. Her cat curled itself around my ankle and then jumped onto the table. She and her husband, a heavy machine operator, were paying for an expensive internet service because school-provided hot spots were not reliable. Still, she said, her kids were falling behind.

After two days, I drove back to Austin. I am a journalist, not an activist, but that does not mean I do not grapple with conflicting emotions, or that I am not considering my own values and choices as I report. I wondered, as I drove home, whether my time would be better spent as a social worker or an educator, making a direct impact. But somewhere between Houston and Austin, I remembered what the retired banker said to me about being stuck behind the Pine Curtain, ignored by the bigger, more politically powerful cities in Texas. “Thank you for visiting,” he had said. “Thank you for telling our story.”

In Austin, mask still on, I scooped my children into my arms and sank back into my life. The pandemic felt so indefinite that I was forced to accept my shelter as my home. The cooking, the games, even the hours I spent playing Judge Judy during my kids’ squabbles were part of this.

The day after I got back from Jasper, the kids and I walked to Waller Creek in downtown Austin. Once we carefully descended a muddy slope to get to the water, there was always a challenge for my preschooler: to cross the creek without getting wet. The stepping stones were far apart. Once he crossed, timidly at first, bravely the more he did it, he always turned back to give me a grin. “I did it! I did it, Amma!” It didn’t matter to him whether he got wet or not, only that he had pushed forward. It was a simple expression of triumph by the creek, our creek. After lunch, I traded off with my husband, who started a project with the kids while I began writing my story about Jasper.