The Lonesome Dove Collection includes the award-winning miniseries’ final shooting script autographed by the entire cast. (Photo by Kevin Stillman)

On the seventh floor of the Alkek Library in the middle of Texas State University, I take in windowed views of the spring-fed San Marcos River and the hilly, wooded alma mater of Lyndon Johnson, and then I walk through a place that always feels like a piece of home. The newly expanded Wittliff Collections has reopened following a year of remodeling, with more space now for displaying the wealth of photography in the archive’s holdings, which ranges from a centennial of the great Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Lee to the Texas prison-farm artistry of Danny Lyon.

The grand reopening features three new photography exhibits: A Certain Alchemy and Fireflies, retrospectives of the Beaumont-based stylist Keith Carter, and Nueva Luz/New Light, which presents new acquisitions from top photographers in the Southwest and Mexico. After exploring the photography exhibits, I head to a fourth new exhibit, this one involving writing, called The Lightning Field: Mapping the Creative Process. Assistant Curator Steven L. Davis assembled the exhibit not only to celebrate the achievement of Southwestern talents such as Larry McMurtry, Katherine Anne Porter, and John Graves, but also to show students, scholars, and visitors a glimpse of the rocky and potholed roads that most authors travel. Davis knows something about these roads himself: He recently published an important new biography, J. Frank Dobie: A Liberated Mind.

Positioned like a philosophical guardian near the entrance of the Southwestern Writers Room, which houses Davis’ new exhibit, is a rough-hewn, bronze statue of John Graves, but sculptor (and prize-winning cartoonist) Pat Oliphant afforded a gentle man the scale of a pro basketball center. A display in a glassed-in case nearby reflects the growing stature of the Collections: It follows the body of Cormac McCarthy’s work and details the acquisition of his papers, from the young writer’s early novels with Southern themes to the turbulent Blood Meridian, from the exquisite All the Pretty Horses to the post-apocalyptic The Road—books that have earned him the National Book Award and a Pulitzer, and a movie adaptation that garnered an Academy Award for Best Picture.

The Lightning Field fills three walls of similar display cases in the Writers Room. The first thing I focus on makes me laugh: Posted on the wall is an enlarged replica of a check Gary Cartwright received from Columbia Pictures in 1975 for $1.12. Options and soaring hopes for movies to be made from one’s work are not all that rare, but numbers like those are the usual plunk of reality.

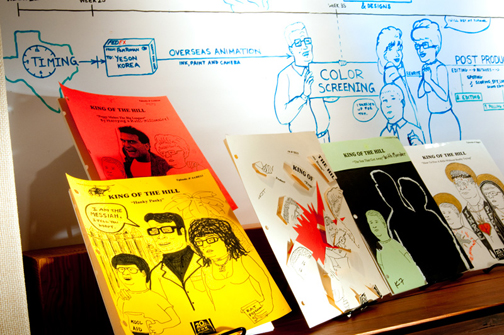

Hand-decorated script covers from the long-running King of the Hill animated series number among the Witliff’s treasures. (Photo by Kevin Stillman)

About 20 years ago, I realized that the evidence of my working life was not going to survive storage in my attic. That evidence is just paper—manuscripts, letters, galley proofs from a few books—but those papers matter to me, and so does anyone who might one day have an interest in them. So, I followed the lead of Cartwright and other friends and entrusted them to the Southwestern Writers Collection, the initial collection that Bill and Sally Wittliff launched at Texas State (then Southwest Texas State) in 1986. I find with pleasure that Steven Davis has given me a space in the new exhibit.

I put on reading glasses to make out words I wrote on a thin stack of typewritten manuscript: “A false start, written when I was in graduate school in Austin in 1971, that became the novel Deerinwater.” Davis’ display text observes that the book was not published until 13 years later.

If hanging on to such things is hubris, I look around this room and know I’m in good company. Elizabeth Crook, in writing her novel about the Texas Revolution, Promised Lands, constructed a calendar timeline that is so minutely and gracefully written that the marks of ink on paper resemble some exotic tapestry. Arranged below the calendar are complimentary but also exacting letters from her editor, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis—not a bad vote of confidence for a young novelist. Just below, the display for the late Edwin “Bud” Shrake contains part of a page he ripped from an English-language newspaper while living in Rome in 1962. The short feature was about Elizabeth Ann Seton, a founder of schools and hospitals and the first American the Catholic Church canonized as a saint. That newspaper story inspired his classic novel about a Texas frontiersman, Blessed McGill.

Several years ago, I spent some evenings with James Crumley, the late Texas-born mystery novelist who much preferred living in Mon-tana. He had the most delightful wheezing laugh. Crumley has been lauded by peers and authorities for writing detective fiction’s all-time best first sentence in a 1975 novel, The Last Good Kiss. I can hear that laugh again on seeing how Davis arranged six manuscript pages in which Crumley kept trying to get the magic right. The end result: ”When I finally caught up with Abraham.Trahearne, he was drinking beer with an alcoholic bull-dog named Fireball Roberts in a ramshackle joint just outside Sonoma, California, drinking the heart out of a fine spring afternoon.” Even in the final draft, he had to take out his pen and insert “just!’

In the corner of the room, I learn the story of Jovita Gonzalez, a pretty young woman from the Rio Grande town of Roma, who, in the 1920s, became J. Frank Dobie’s student and protegee. She started writ-ing a novel about racial struggle in South Texas, but then married and stopped writing for publication. In the 1970s, an interviewer asked her why she just quit. Before she could reply, her husband interjected firmly that all the manuscripts had been destroyed. After the couple died, copies of some manuscripts that she had hidden away were discovered. Caballero had evolved into a portrayal of an autocratic patriarch. It was published to wide acclaim in 1996.

And there are many more: displays devoted to Sam Shepard, Katherine Anne Porter, Beverly Lowry, Stephen Harrigan, Shelby Hearon, William Hauptman-fine cameos all.

Bill Wittliff told me once that when he was a young University of Texas student enthralled by having met Dobie, the grand old man of cowboy folklore gave him a glance and asked what his major was. “Journalism;’ Wittliff replied.

“Journalism!” Dobie erupted. “Boy, you need to get some fiber in your brain.”

Dobie had the luxury of faculty tenure but never bothered to add a Ph.D. to his degrees in English. The administration allowed him to carry on in his oft-cantakerous ways because he was prolific, producing 20 well-received books. He died in 1964. His wife, Bertha, followed him in 1974, and the remaining estate was inherited by their nephew, ornithologist Edgar Kincaid Jr.

Before his death, Dobie had willed many of his papers to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. By 1985, the year that Kincaid died, Bill and Sally Wittliff had founded the highly respected Encino Press; the best-known of their titles was Larry McMurtry’s book of essays, In a Narrow Grave. Sally pursued a legal career while Bill enjoyed growing success as a moviemaker. (He’s most famous for his 1989 adaptation and production of McMurtry’s masterpiece, Lonesome Dove.) Following Kincaid’s death, an estate sale of Kincaid’s and Dobie’s posses-sions was scheduled, and the executor called Bill and asked if he wanted Dobie’s desk. Bill went over to buy it, and then noticed several stacks of boxes. They contained a great deal more of Dobie’s papers, which Bill assumed would go to the Ransom Center. But the executor told him those curators had not shown interest in taking on more Dobie papers. After calling Sally to make sure the check would clear the bank, Bill bought the collection, and administrators and librarians at the university in San Marcos were delighted to give the materials a home. The Wittliff Collections originated with this gift, and the resulting archive has brought enormous prestige to Texas State.

Some critics and scholars have wondered if more emphasis on the photo collections and traveling exhibits will leave the literary papers collecting dust. Bill Wittliff is himself an excep-tional photographer. But the Wittliffs signaled their intent early on with the acquisition of a rare 1555 edition of Cabeza de Vaca’s adventure in survival-the very first book on Texas and the Southwest. Wittliff says, “The idea has always been that this would be a place to conserve these treasures of our culture, but also to inspire those people who have the itch to create but not yet the courage …. I know if I had been able to experience a place like this when I was 17 or 18 years old, I would have had the courage to write way earlier than I did.”

Jan Reid’s forthcoming books are Texas Tornado: The Times and Music of Doug Sahm (with Shawn Sahm) and a biography of Ann Richards (both from University of Texas Press), and the novel Comanche Sundown (TCU Press).