Ask three vintners what it means to make “natural wine” and you’ll get three different answers, probably accompanied by a shrug.

“Oh, the loadedest of loaded questions,” says Regan Meador of Fredericksburg’s Southold Farm + Cellar. “At this point, it’s more of a marketing term, and we shy away from those.”

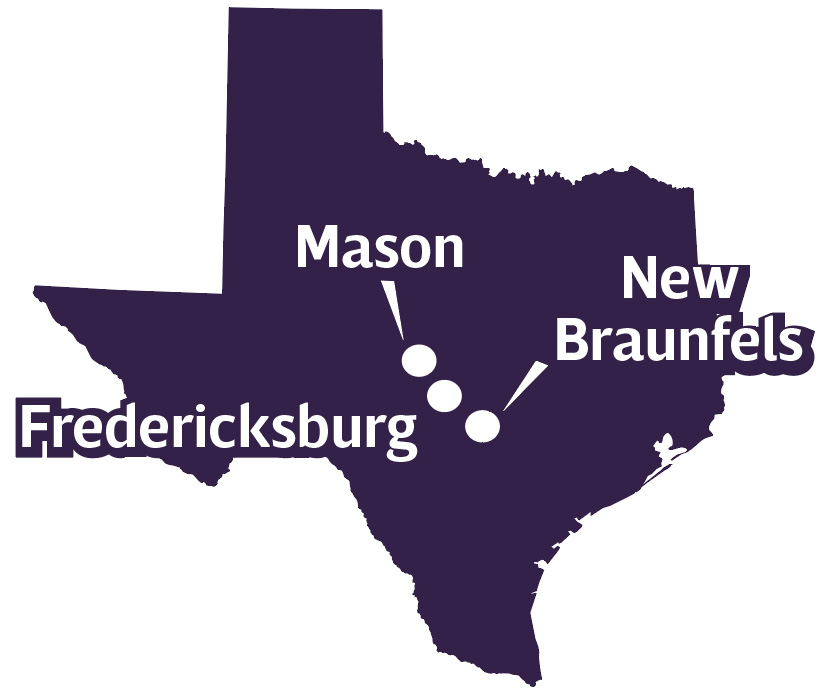

Unlike products labeled “certified organic” or “non-GMO,” natural wine doesn’t have a checklist of attributes or an independent seal of approval. And yet, natural wine production is on the rise across the country. Currently, there are three Texas outfits—Southold, La Cruz de Comal Wines, and Robert Clay Vineyards—growing grapes and making wine following the natural credo.

Southold Farm + Cellar owner Regan Meador

Think of natural wine as less is more. Growers do as little as possible to the grapes on the vine, and winemakers do as little as possible to the wine in the barrel, avoiding chemical pesticides, insecticides, and preservatives, as well as color and flavor additives.

But this simple explanation leads to more questions. If natural winemakers are hands-off, what are other folks doing?

Just as farmers and ranchers make choices about fertilizers and pesticides, so do grape growers. And then there are purely cosmetic decisions. Even a discerning drinker might be surprised to know there’s something called Mega Purple, a grape-juice concentrate many mass-production wineries rely on to deliver the hue we expect from a robust pour.

“There are people who look at natural wines and think everything else is unnatural,” says Andreea Botezatu, an assistant professor of enology—or the study of wine—at Texas A&M University. “There’s an argument that conventional wine is the fast food of wine. Yes, there are big corporations making cookie-cutter wine, but others do a very good job of expressing terroir [or the environmental characteristics present in a wine]. Their interventions are for the quality of the wine and the pleasure of the consumer.”

As any farmer will tell you, agriculture is a gamble. Pesticides exist because bugs are a grape’s worst enemy—unless you count powdery mildew, flash floods, or any of the other crop-destroying pathogens and weather patterns that flourish in Texas. Chemical solutions to those environmental challenges are part of a conventional winemaker’s toolbox, and many in the industry say there’s a way to use them responsibly. By forgoing those tools, natural wine producers leave themselves more exposed to nature’s whims, making their own jobs harder. But natural winemakers are nothing if not dogged.

Lewis Dickson, owner of La Cruz de Comal Wines in Canyon Lake, doesn’t adhere to wine trends. In 2007, after years of experimentation, he stuck to just two little-known grapes when planting his 3-acre vineyard: blanc du bois and black Spanish.

Because of the extra environmental risks, some popular varietals—cabernet, for example—just won’t make the cut in some growing regions. If you’re going to make natural wine in Texas, you have to choose grapes that can withstand the heat. “In my opinion, the Hill Country is not sauvignon country,” Dickson says. “It’s a late-ripening grape, and late-ripening grapes do better in areas that have four distinct seasons.”

Dickson didn’t set out to be a natural wine flagbearer. “That’s just how I was taught,” he says. “I make biscuits the way I make them because that’s the way my mother taught me.” He learned winemaking from a California friend, who learned from his Tuscan grandfather. “My wine is completely natural—no yeast, no acid, no sugar, no sulfites—but that’s not the banner I’m principally waving,” Dickson says. What matters to him is that you like how his wine tastes.

Dickson didn’t set out to be a natural wine flagbearer. “That’s just how I was taught,” he says. “I make biscuits the way I make them because that’s the way my mother taught me.” He learned winemaking from a California friend, who learned from his Tuscan grandfather. “My wine is completely natural—no yeast, no acid, no sugar, no sulfites—but that’s not the banner I’m principally waving,” Dickson says. What matters to him is that you like how his wine tastes.

Meador, of Southold Farm + Cellar, has worked out a Texas-friendly analogy for why he prefers natural wine. “There are two ways you can grill a steak,” he says. “You can take a nice cut and put it in a bag with a bunch of Italian dressing, throw it on a really hot grill, cook it all the way through, and slather it with barbecue sauce. Some people think that’s good, and that’s OK. But another way is to buy a nice cut, season it with some salt and pepper, and cook it just a little.”

Before relocating to Fredericksburg in 2017, Meador, a native Texan, spent five years making wine in Long Island, New York. When he ran into roadblocks expanding Southold’s original location, he and his wife sold the farm and headed south, where land was cheaper. He saw an opportunity to help blaze a new trail.

Think of natural wine as less is more. Growers do as little as possible to the grapes on the vine, and winemakers do as little as possible to the wine in the barrel.

Like Meador, Dan McLaughlin knows what it means to start over. He started farming Robert Clay Vineyards in 2012. The 50-acre Mason property, planted by a previous owner in 1996, was in such rough shape, McLaughlin made the agonizing decision to chainsaw the entire lot and let the vines regrow. “It was give up or go all in,” he says. In 2013, he harvested no fruit. In 2014, he picked 21 tons, and he has increased production nearly every year since.

After five years of conventional farming, McLaughlin began transitioning to organic growing and additive-free winemaking in 2017—a U-turn almost as big as bulldozing his vines. He readily admits looking to Meador and Dickson for advice, usually before going his own way. “I don’t listen to people too long,” McLaughlin says. “If I have a gut feeling, I follow it.”

For him, that means embracing the Old World concept of terroir and acclimating customers to the idea that this year’s wine will differ from the next. “One thing I started to dislike about conventional wine is that, at least in the United States, it’s got to taste exactly the same every year,” McLaughlin says. “And I get that: When people buy milk, they want it to taste like milk.”

But the uniqueness of natural wines is what makes them so special. “Natural wines express a sense of place, of time, the conditions of the year. They’re not made to be reproducible, year after year after year,” A&M’s Botezatu says. “They’re an expression of the moment.”

La Cruz de Comal Wines

Try the Petard Blanc, a white that’ll have you seeing the French fireworks for which it was named.

7405 FM 2722, New Braunfels. 830-899-2723;

lacruzdecomalwines.com

Southold Farm + Cellar

Try the touriga nacional. Made from McLaughlin’s grapes, it’s a garden in a glass: flowers, roots, and herbaceous funk.

330 Minor Threat Lane, Fredericksburg. 512-829-1650;

southoldfarmandcellar.com

Robert Clay Vineyards

Try the pétillant naturel, a crowd-pleasing entry into natural wine for lovers of rosé and bubbles.

113 Austin St., Mason. 325-261-0075;

robertclayvineyards.com