Fifteen of Texas writer Larry McMurtry’s typewriters were up for auction on Memorial Day.

Larry McMurtry pulled off U.S. 84 outside of Waco 30 years ago and circled into the parking lot of the Egg Roll House Chinese Restaurant. When he got out of his car, he approached two women who had hastily set up a card table and were trying, in earnest, to sell T-shirts and hats—memorabilia. One shirt said, “Hey Vern! WEIRD ASSHOLE COME OUT.” Another said, “MT CARMEL ERUPTS. A MESSAGE FROM GOD … THE SINFUL EPISODE!” After exchanging words with the women for a few minutes, McMurtry purchased three T-shirts and one hat. A portion of this event is detailed in a 1993 article by McMurtry for The New Republic, where he describes his road trip only weeks after the Branch Davidian tragedy. For many in the collecting world, this story constitutes a sacred event; it’s an event of singularity, one that auctioneers, appraisers, and collectors call “provenance.” It’s the origin story of an object.

You could have purchased these items this past Memorial Day through “The Estate Auction of Larry McMurtry,” hosted by Vogt Auction Galleries of San Antonio. Lot #188: Group of (4) Waco Siege Souvenir Shirts and Hats—“Hats” should be singular—sold for $720. There were 3,547 live participants bidding online, over the phone, and in person for 300 of the iconic author’s personal effects. These objects ranged in price and significance, from personal copies of signed first editions to furniture and firearms.

Larry McMurtry’s acquisition of the items in Lot #188: Group of (4) Waco Siege Souvenir Shirts and Hats was likely less about collecting and more about making a gesture of human connection.

The story of Lot #188 was not included in the catalog description provided by Vogt Auction. This was gleaned from The New Republic piece, where McMurtry looked for meaning in the aftermath of the 51-day siege that led to the deaths of more than 70 members of the Branch Davidians and four officers of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. While provenance can add value and authenticity to an object, it’s hard to account for our desires to collect and own. Not a fan of the term “collector,” according to his writing partner, Diana Ossana, McMurtry made a point of italicizing the word objects in books on collecting, often saying the objects we obsess over can, just as easily, be discarded at the drop of a hat, much like the people we love. So, what was McMurtry’s relationship to these objects? What’s our own?

The walls of the auction house in San Antonio are covered in taxidermy javelina and boar heads, prints of J. Frank Dobie, and primitive Southwest landscapes. From the ceiling hang banners for the University of Texas and Texas A&M, as well as for the Texans and Cowboys. I’ve been to different types of auction houses over the years, not to mention junk shops, estate sales, and flea markets across the country, but I haven’t seen one exuding this level of rugged machoism. Even though the displays are clean and orderly, the room looks trapped between a John Ford film and an episode of Yellowstone. To be fair, one would expect as much from the personal estate of a man who rewrote the legacy and narrative of Texas literature—though the sports banners certainly weren’t his.

To be doubly fair, I’m not even at this auction. I’m in Raleigh, North Carolina, playing “cars” with my 4-year-old nephew. We’re driving his Hot Wheels around the rug in his room, then parking them in their invisible garages. As much as I want to be in San Antonio, I’ve had this cross-country road trip scheduled for months, and the truth is most people bid remotely today. I can easily bid through the LiveAuctioneers app on my phone. Every now and then my nephew picks up a Hot Wheel and shows it to me, and when he puts it back down, I quickly open the app: Lot #34: Hermes 3000 Typewriter has just sold for $6,000.

Rob Vogt (left) of Vogt Auction Galleries in San Antonio auctions off a copy of Larry McMurtry’s novel Boone’s Lick.

My man on the ground is standing at the back of the auction house. Brandon Kennedy has written on McMurtry auctions and is a rare books and art expert for the international auction house Bonhams. Similar to McMurtry’s brief work as an auction bidder for hire, Kennedy is my trusted source. He knows which McMurtry prices are reasonable and which ones have been driven past the point of sanity. Days before the auction, Kennedy tells me how it won’t be a logical affair, that “everything is going to be inflated and over the top because people are going to come wanting to have a piece of the legacy and the author and the myth of these objects.” Apparently, people will be swayed by nostalgia and celebrity, and he’s right. I check my phone: Lot #47: Larry McMurtry’s Bookplate in Bronze, a small paperweight sculpture in the shape of a stirrup, sells for $36,000. Its original ask? $1,000 to $2,000.

Kennedy tells me Lot #61: Signed In A Narrow Grave 1968, Larry McMurtry, a slim volume of McMurtry’s early, defining essays, is perhaps the most desired item from the range of books, and others think it might compete for a top auction price. But in the end, it only sells for $10,800.

There are several other items that interest me, but most of them are out of my price range, even at initial ask. I’ve consulted an antique arms dealer at Jackson Armory in Dallas about Lot #77: Japanese Arisaka Type 99 ‘Last Ditch’ 7.7x58mm Bolt-Action, a rifle given to McMurtry by his cousin Robert Hilburn on his return from WWII. This was the same man who gave McMurtry his first collection of 19 books prior to entering the war, including Sergeant Silk: The Prairie Scout—the first book McMurtry read, the spark that set the whole forest ablaze. But the gun dealer kind of shrugs when looking at the picture and tells me it’s been “duffle cut,” meaning the wooden stock under the barrel has been cut so the gun could be disassembled and transported back from the theater of war in a duffle bag. He says this as if I might already understand it, but I don’t.

The dealer explains that this gun is in pretty bad shape, and guns are all about “condition, condition, condition.” I would assume connecting the gun to the man who gave McMurtry his first books would be important, especially when it comes to an object McMurtry kept his whole life, but the gun dealer speculates it will merely double the asking price of $200 to $300. “Maybe $800 if it was in good condition,” he says.

As my nephew shouts at me to follow him to the backyard, the gun brings in $1,020. So, the provenance did give the rifle a bit of a boost after all.

I watch my nephew drive his remote-control monster truck in circles around his English Labrador, while the auction house bubbles with “lookie-loos” who want to “touch the hem of the garment,” Kennedy says. Perhaps I’m no different. Apparently, it’s a festive scene. While auctioneer Rob Vogt wields a hammer in front of a large, framed Texas flag, his father, Gene Vogt, sits at a table to the side cracking jokes and telling anecdotes. “You’ll never see these items again!” Gene shouts. He’s dressed in a dark suit and shirt, with a matching, nondescript baseball cap, looking every bit a Logan Roy.

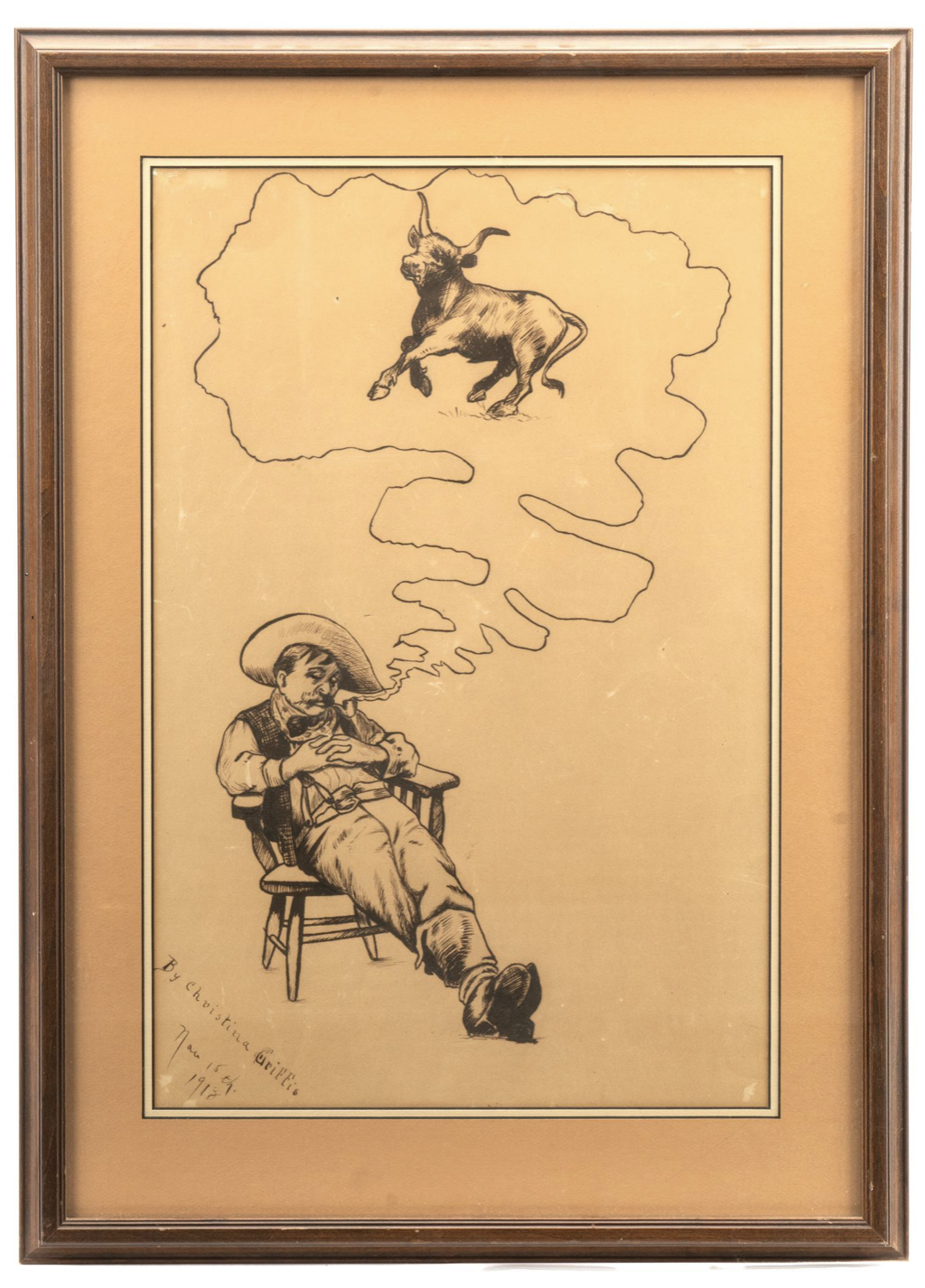

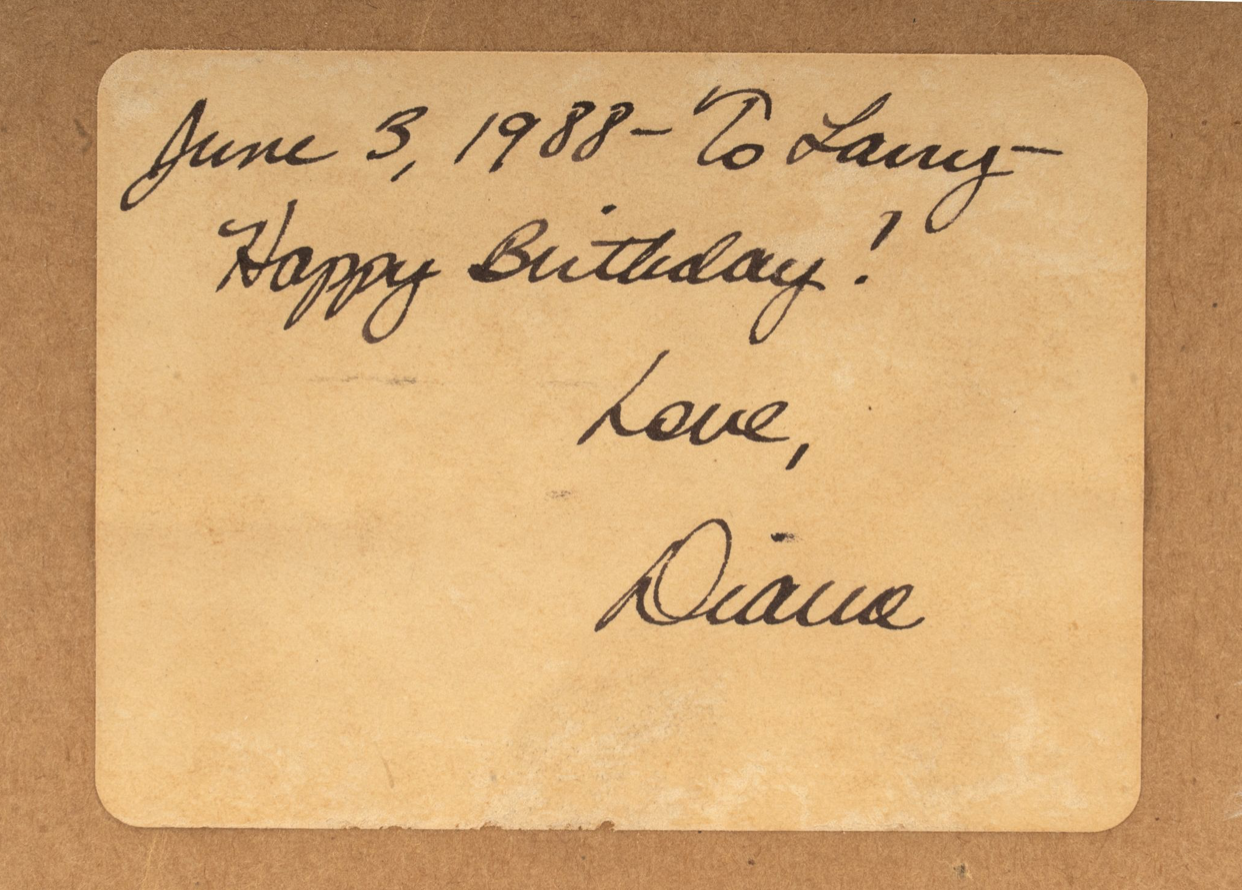

Lot #163: Christina Griffis, Dreaming Cowboy, 1913 comes up, a framed ink drawing Ossana inscribed to and gave McMurtry for his birthday in 1988. Living together for 30 years, the drawing hung outside her bedroom door in McMurtry’s Archer City home. Ossana bids on the item early, wanting it back. But as bidding eclipses the $300 to $500 ask, she stops. “It’s the first really personal, meaningful gift I gave him,” Ossana says. But as the object moves farther and farther out of her grasp, it becomes a prized collectible and not a returned gesture among best friends. The irony is that this friendship, this connection between Ossana and McMurtry—the reason she wants it back—is the exact reason the bid skyrockets. Its provenance helps propel a wild premium. Lot #163 eventually sells for a staggering $36,000, an amount Kennedy assures me is well beyond its actual value.

I realize I’ve stepped into IPO stock territory and there’s no way to gauge an item’s final sale price. Because of that, I decide to place a pre-bid on something down the line and let it all go. I quickly bid on Lot #224: Attrib. Nicario Jimenez Quispe, Peruvian Retablo, a painted wooden box portraying figures who are trying on different decorative masks; the wall behind them is covered ceiling to floor with masks of various shapes, sizes, and colors. On the top of the wooden frame, someone has tacked an oval, handwritten note: “Interior View of the Novelist’s Imagination Re: Characters.” It is a small item, 10 by 12 by 4 inches, but it would look incredible set back between books on a shelf—especially when I say to a visitor, “Oh, that? Actually, it was Larry McMurtry’s.”

As McMurtry wrote in The New Republic, “From tragedy it is seldom but a step to memorabilia.” And that’s what most of us have been looking for—all except for the Ossanas of the world. But McMurtry dabbled in memorabilia as well, even if, to his mind, it took a different form. Ossana tells me McMurtry probably purchased “Lot #188: Group of (4) Waco Siege Souvenir Shirts and Hats” because “he valued the ordinariness in human beings,” the ways we could all be alike. She says he was a man of great “sentiment,” ultimately moved by personal connections that deepen our humanity. So, for McMurtry, one can assume that purchasing the T-shirts and hat outside of Waco didn’t so much amount to collecting memorabilia as it amounted to a gesture, an act of connection across an event of inhumane proportion.

Ossana believes McMurtry’s own auction would have been somewhat of a bore to him. For a man who spent so many years scouring bookstores and auction houses, and then found himself on the other side of the collectibles market, Ossana’s quite sure he simply “would have rolled his eyes and walked away.”