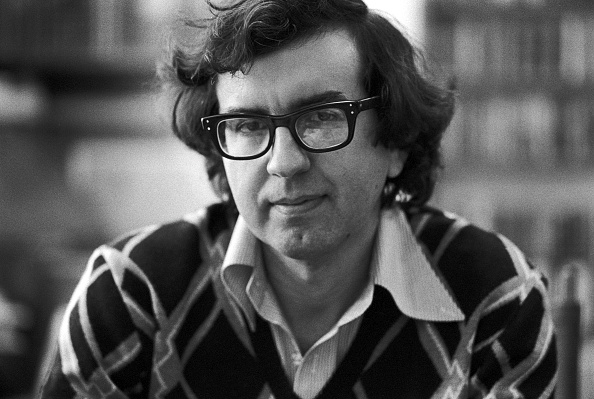

Larry McMurtry, the self-described “minor regional novelist” who came to embody and define Texas literature, has died. He was 84.

Though rightly revered as a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist (Lonesome Dove) and an Academy Award-winning screenwriter (Brokeback Mountain), McMurtry’s role as essayist and more particularly as critic was of vast importance and is also worthy of fond remembrance.

Remembering McMurtry:

Six writers pay their respects to the late Texas writer in this Texas Highways exclusive

Read now >>

We Texans are a famously self-regarding people, and while that can be a virtue, in certain fields of endeavor not measured by the barrel or the bale or a scoreboard, but instead by subjective taste and discretion, pride can goeth before a fall. Such was once the case of our native literature, and we’ve never had a sterner critic of that than Larry McMurtry, the real-life cowboy who spurred our words out of the 19th century and into the present and then back again, albeit with a contemporary eye. Our letters are by far the better for the gauntlets he’d cast down over the course of his career in talks and printed diatribes and the counter-examples he offered with his own works.

McMurtry was the first Texan writer of prominence to dare look back with a jaundiced eye on those who’d come before him, in his words, “the Holy Oldtimers.” This included historian Walter Prescott Webb, naturalist Roy Bedichek, and tale-spinner and lore-miner J. Frank Dobie. In the title selection from 1968’s essay collection In A Narrow Grave, he wrote of them with something less than reverence, and in 1981’s Texas Observer essay “Ever a Bridegroom,” he doubled down, saving his harshest criticism for Dobie, whose collected works were “a congealed mass of virtually undifferentiated anecdotage: endlessly repetitious, thematically empty, structureless and carelessly written.” (He was right; Dobie is seldom read today. McMurtry saw him as a Will Rogers-like figure, more raconteur than literary man, and a relic of a time long past.)

In “Ever a Bridegroom,” McMurtry recalled that “In a Narrow Grave” was his formal and eternal goodbye to the river of his youth: the stories of 1950s small-town life that won him fame in his mid-20s and no small amount of Hollywood cachet: The Last Picture Show; Horseman, Pass By; and Leaving Cheyenne. (The latter two made into the films Hud and Lovin’ Molly, which McMurtry loathed and would later say it “just about killed his father.”) Henceforth, he declared, he would stick to urbanites, the Danny Decks and Aurora Greenways of his Houston novels (All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers, Terms of Endearment) and the Peppers and Harmonys of the contemporary Western states books and the womanizing D.C.-based antiquarian Cadillac Jack.

Never one to rest on his laurels, in looking back on all that had come before 1981, he included his own works (from the “Ever a Bridegroom” essay):

“It took me until around 1972 to write a book that an intelligent reader might want to read twice, and by 1976 I had once again lost the knack. There is nothing very remarkable in this: Writing novels is not a progressive endeavor. One might get better, one might get worse. If I’m lucky and industrious I might recover the knack, or then again I might be very industrious and never recover it.”

Turns out he was both lucky and industrious. And a master of self-contradiction.

Not only did he return to Thalia for books like the underrated, darkly comic Texasville, and his late-period masterpiece Duane’s Depressed, but even as he was banging out “Ever a Bridegroom,” he was hard at work on Lonesome Dove, the last book you’d think Larry McMurtry would ever write and the first book fiction-reading Texans would likely claim today as their favorite.

Unlike the Westerns before it, Lonesome Dove was unsparingly violent, with beloved characters killed off with Game of Thrones-like ruthlessness. Texas Rangers could be heroic or tragically flawed. Albeit in a somewhat perfunctory manner, it tackled the issue of race. It had compelling, well-rounded female characters in Lorie Darling, Clara Allen, and Elmira Johnson. Johnson was a somewhat minor character but nevertheless one whose love of a bad man propels much of the action in the novel, as well as the demises of a half-dozen or so characters, innocent and not-so-innocent alike.

The iconoclast of the Old West picked up the shards of what he’d spent his early career destroying and recast them into a new iconography, one infinitely more complex than its predecessor. And the contemporary literature of Texas—not to mention Texas cinema, on which McMurtry’s influence is broad—is likewise far more interesting and honest than it was when McMurtry discovered it, first via the stories he heard from his cowboy ancestors under the porch light up in Archer City and then in the stacks at the Rice University library in teeming and humid Houston.

In the 1999 essay collection Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, McMurtry lovingly portrayed Houston as: “[M]y first city, my Alexandria, my Paris, my Oxford. It was the place where I could begin to read, and I did, in Rice’s open-stack library. I didn’t know I was going to be a writer, nor did I suspect that the contrast between old and new, province and capital, wild and settled would occupy me for most of a writing life that has now passed the forty-year mark…”

Thank the stars above he was not averse to contradictions, least of all those of the self. For as he described Houston in 1968 as “a city with great wealth, some beauty, great energy, and all sorts of youthful confidence; but withal, a city that has not as yet had the imagination to match its money,” the same could have been said of Texas as a whole that same year. Fifty-three years later, our flights of fancy are fast catching up on our prosperity, and for much of that, we have Larry McMurtry to thank.