“It’s not too often that you just don’t have anything to do,” our guide remarked as we lounged on the sandy shoreline of the Neches River in East Texas, cooling off in the water after a day of canoeing. Across the caramel-tinted river, a dense forest crowded the dirt bluff on the opposite bank. Behind us, our loaded canoes rested on the edge of a broad, empty sandbar, its semicircle beach mirroring the luminous half-moon overhead.

The Big Thicket Association hosts the Neches River Rally each September to raise funds for its conservation mission. At texashighways.com, read expanded coverage of the association and the rally.

Natural Habitat

Above, a beaver dam forms a pool on a creek that feeds Banks Bayou. Right, a campsite n a picturesque Neches River sandbar.

Big Thicket Paddling

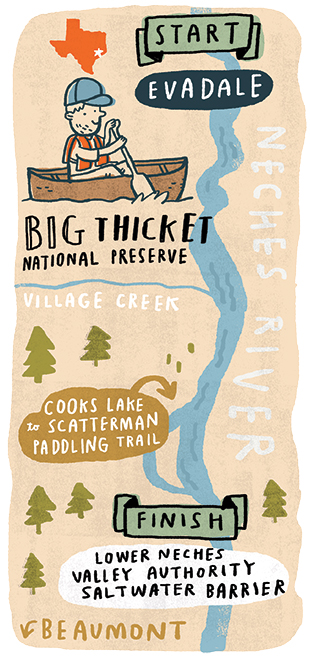

Big Thicket Outfitters offers a range of guiding and boat-rental services on the lower Neches River, Village Creek, and the Cooks Lake to Scatterman Paddling Trail. Canoe and kayak rentals cost about $45 a day, with additional costs for customized guiding services. Call 409/786-1884.

The Big Thicket National Preserve encompasses 80 miles of the Neches River and 35 miles of Village Creek, including most of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s 21-mile Village Creek Paddling Trail. For information on paddling in the preserve, including permits and local outfitters, call 409/951-6700.

The 4.8-mile Cooks Lake to Scatterman Paddling Trail, a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department-designated trail, is accessible from the boat ramp at the Lower Neches Valley Authority Saltwater Barrier.

Happy Trails

The 4.8-mile Cooks Lake to Scatterman Paddling Trail branches off the Neches River and explores beautiful sections of cypress and tupelo forest. Above, the weathered trunk of an old cypress known as the “Madonna tree” bears a faint resemblance to artistic depictions of the Virgin Mary.

True, we’d been bobbing in the shallow rapids for a half-hour or so to keep cool on that sunny July afternoon. But it would be misleading to imply we had nothing to do.

We’d paddled about 10 miles that day. Soon we would set up our tents, cast a lazy fishing line, cook a camp-stove dinner, and start a driftwood fire to accompany our tall tales and guitar strumming. We had plenty to do—just not the type of checklist fodder that dominates the clock-driven days of routine life.

When floating the Neches River through the depths of the Big Thicket, I was beginning to realize, it’s best to put your schedules and anxieties on the backburner and let the river’s current, mean-ders, and scenery be your guide. In other words—go with the flow.

I had embarked that morning from a boat ramp near Evadale with Texas Highways photographer Brandon Jakobeit and guides Gerald Cerda and Jason Connolly of Big Thicket Outfitters. In two canoes loaded with ice chests, cooking gear, tents, bedding, folding chairs, clothes, and a guitar, we followed the lower Neches River through the Big Thicket National Preserve to a takeout point in north Beaumont. For three days, we floated through a diversity of Big Thicket waterscapes, soaking in the beauty, culture, and history of this inconspicuous East Texas natural wonder.

As we paddled around the first few bends in the river, it became apparent that we had gotten lucky with nearly ideal conditions—clear skies, a swift current, and fresh sandbars. Months of flooding in 2015 and early 2016 had scoured brush and trash from the sandbars and built them up with freshly deposited sand. Moreover, the river level had dropped in the previous weeks, uncovering the sandbars and channeling the river into a consistent flow.

As we paddled around the first few bends in the river, it became apparent that we had gotten lucky with nearly ideal conditions—clear skies, a swift current, and fresh sandbars. Months of flooding in 2015 and early 2016 had scoured brush and trash from the sandbars and built them up with freshly deposited sand. Moreover, the river level had dropped in the previous weeks, uncovering the sandbars and channeling the river into a consistent flow.

“The river is constantly changing,” noted Cerda, who started Big Thicket Outfitters in 2012 after exploring the lower Neches recreationally since his childhood. “You know that saying? A man never steps in the same river twice, because it’s not the same river, and he isn’t the same man.”

The Neches River originates from a spring in Van Zandt County and flows southeast 416 miles before emptying into Sabine Lake and the Gulf of Mexico. Starting at Town Bluff Dam, which forms B.A. Steinhagen Lake near Jasper, the river serves more or less as an 80-mile eastern boundary of the Big Thicket National Preserve.

The Big Thicket ecosystem once covered nearly 3 million acres, from the Neches west to the Trinity River, and from Woodville down to Beaumont. Only about 3 percent of the Big Thicket survives intact today, according to the National Park Service. The Big Thicket National Preserve protects 112,000 acres in a patchwork of 15 units across seven counties. Our float trip gave us a river-level view of the Big Thicket’s renowned ecological diversity, particularly the bottomland hardwood forests bordering the river and the sloughs and bayous of cypress and tupelo forests.

The Neches River’s sandbars were a central part of our canoe trip. We spent most of our days paddling downriver, sometimes leaving the main channel to explore swift-moving side courses, swampy lakes, and bayous. We docked on the sandbars for swimming and picnic breaks, and for camping at night. (Most moderately fit people could handle this trip if they’re comfortable with being in a canoe for a few days and tent-camping.) Because sandbars are part of the public streambed, they’re open for camping. The national preserve requires permits for camping in its section of the river; permits are free and easy to acquire, either by phone or at the visitor center in Kountze.

Sandbars have always been one of the Neches River’s defining characteristics. The first Europeans to record their observations of the river in the 1500s called it Río de Nievas, or River of Snow, because of the white sand. There are at least two explanations for how the Neches got its contemporary name—one holds that a Spaniard named the river after the Neches Indians, a Caddoan tribe from the region; another is that the Spaniards adopted the name used by the Caddos, who called the river “nachawi,” their word for the bois d’arc tree. Whatever the case, historians believe that the natives of the area traveled by rivers and creeks as an alternative to the dense thicket. It’s hard to imagine that these pre-Texans didn’t frequent the sandbars as well.

Different chapters of Neches River history and culture bubbled to the surface throughout our float. We encountered fishermen angling for catfish and crappie with trotlines and fishing poles as well as funky wooden fishing cabins—some houseboats and some built on stilts on the shore. Near Vidor, we docked briefly to visit with jovial riverside residents kayaking and swimming off their back porches.

Different chapters of Neches River history and culture bubbled to the surface throughout our float. We encountered fishermen angling for catfish and crappie with trotlines and fishing poles as well as funky wooden fishing cabins—some houseboats and some built on stilts on the shore. Near Vidor, we docked briefly to visit with jovial riverside residents kayaking and swimming off their back porches.

The Neches River basin has long been timber country; loggers once used this section of the river to float timber to mills in Beaumont. Large cypress tree stumps with distinct rings around their bases are remnants of a century-old logging technique, Cerda said. Loggers would score the trunks in the summer to injure the trees and then return in the winter to cut and float them to the mill.

Early in the trip, we canoed under an old railroad swing bridge with a massive gear on its underside, possibly a mechanism for the bridge to turn and make way for riverboat traffic, which mostly ceased by 1900. We also paddled by the rusted remnants of shoreline docks for early 20th-century oil-and-gas operations, along with infrastructure for ongoing energy production in the Big Thicket.

With the exception of birds, wildlife in the Big Thicket kept a pretty low profile during our trip, but creature clues greeted us at every stop. Tracks in the sand and mud hinted at deer, raccoons, birds, dogs, and feral hogs. During the trip, I spotted three deer, a beaver, turtles, alligator gar, mullet fish, minnows, and an unidentified water snake.

Also on the sandbars, we found numerous shells from freshwater bivalve mussels, some as large as taco shells. The mussels scoot around the sandy river bottom, filtering water through their bodies to feed on microorganisms. When the water recedes, you can see the mussels’ beautifully random paths in the sand, resembling the squiggly doodles on a junior high notebook.

Each morning at dawn, a growing chorus of birdsong ushered in the day. Occasionally, the rattle of a woodpecker would roll across the river valley. I saw a pileated woodpecker cross the river with its distinctive flap-swoop-flap-swoop flying motion. Cardinals, little blue herons, wood ducks, vultures, and great egrets accompanied us throughout the journey. And a first for me: swallow-tailed kites—a raptor characterized by its scissortail and sleek black-and-white body—circled overhead a few times.

At night, the sounds of owls, cicadas, crickets, and frogs provided the backdrop for our campfire tales. On our second night of camping, shortly after bedtime, a motorboat with a spotlight startled me awake and called to mind the unsettling banjo strains of Deliverance. Turns out it was some locals “bullfrogging”—hunting for fat frogs to fry.

The day before embarking on the canoe trip, I had visited the Big Thicket National Preserve Visitor Center in Kountze to study up on my surroundings. Built in the shade of a loblolly pine forest and set in a Craftsman-style log building, the center presents exhibits about the Big Thicket’s history, ecology, and wildlife, such as alligators, bobcats, mountain lions, and snakes. Historically, black bear, jaguars, and red wolves also roamed the area.

“People ask about bears, about mountain lions, about snakes,” Ranger Mary Kay Manning said. “And I tell them, honestly, the things I’m worried about are mosquitoes and ticks because of the diseases they can transmit. The mammals are going to stay away from people.”

Thusly warned, we brought plenty of bug repellent along. As it turned out, the mosquitoes weren’t a major factor on the river or the sandbars (we stayed out of the forest for the most part), but they could be an annoyance at dusk. Just be sure to keep mosquitoes out of your tent for the night!

Big Thicket National Preserve’s most popular paddling destination is Village Creek, a tributary of the Neches River that meanders southeast through the Piney Woods and Big Thicket. Big Thicket Outfitters does about 90 percent of its canoe and kayak rental business on Village Creek, Cerda said, because the creek is good for shorter trips, ranging from a couple of hours to overnight camping trips. Village Creek runs through similar terrain as the lower Neches, but the waterway is narrower. Near Lumberton, Village Creek State Park offers developed campsites with bathrooms.

But our river journey provided a broader perspective of the lower Neches. Dense hardwood forests dominated the shoreline for the first three-quarters of our trip. Sixty-foot, spindly trees such as water oak, river birch, and loblolly pine crowded each other along the precipice of the dirt bank, looking like marathon runners jockeying for position at the starting line. Erosion exposed the trees’ roots on the bank, while willow trees reached their green, leafy branches out over the river, providing moments of shade as our canoes floated beneath. Yaupon holly and sweetgum filled the understory, and flowering vines like trumpet creeper and wisteria added splashes of red and orange to the greenery.

But our river journey provided a broader perspective of the lower Neches. Dense hardwood forests dominated the shoreline for the first three-quarters of our trip. Sixty-foot, spindly trees such as water oak, river birch, and loblolly pine crowded each other along the precipice of the dirt bank, looking like marathon runners jockeying for position at the starting line. Erosion exposed the trees’ roots on the bank, while willow trees reached their green, leafy branches out over the river, providing moments of shade as our canoes floated beneath. Yaupon holly and sweetgum filled the understory, and flowering vines like trumpet creeper and wisteria added splashes of red and orange to the greenery.

I didn’t see a single alligator on this trip, although I kept my eyes peeled for them, especially as we ventured into the lakes and sloughs that characterized the last quarter of our trip. Not far from Beaumont, we detoured off the Neches River and onto Scatterman Lake to follow the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department paddling trail known as “Cooks Lake to Scatterman.” The 4.8-mile loop is the setting of the Big Thicket Association’s Neches River Rally, an annual September event for canoeists and kayakers to explore this section of the Neches River, Pine Island Bayou, and offshoot lakes and sloughs.

The paddling trail took us through the fairy-tale setting of a sun-dappled slough full of cypress and tupelo trees, where the light took on a shadowy, emerald quality. Witches-beard lichen and verdant ferns sprouted from the gnarly old trees. We maneuvered our canoes around the trees’ knobby knees and ducked below massive spider webs in the branches. The forest muffled all sound except for the water trickling around our paddles. With a flash of white and a rustle of leaves, a hidden great egret splashed the surface and flapped toward the sky.

Leaving the silence of the water forest and rejoining the river, we paddled our way to a ramp near the Neches River Saltwater Barrier and pulled our canoes ashore. We were tired, hot, and sun-beaten, but in the calm, clearheaded, and refreshed way that comes from immersing yourself in nature for a few days.

“They call this a hidden gem,” Cerda said as we surveyed the journey. “If it is a hidden gem, would more people come here if they knew about it?”

I tend to think so. Three months later, I returned to the lower Neches River, this time with my family in tow, for the Neches River Rally. We paddled along the leafy riverbank, spotting egrets and jumping fish, and marveled at the wondrously odd cypress trees that stretch from the water’s murky surface to the sky. I could tell my family was just as captivated as I was.